The moon is shrinking and shaking, Nasa says

Our neighbour has shrivelled up like a raisin

The Moon is shrinking – and shaking as it does, according to new Nasa data.

Over the last decade, scientists have established that as the inside of the Moon cooled, it shrivelled up a like a raisin. That left it riven with cliffs called "thrust faults", marked all over its surface.

Now a new analysis, using data from Nasa missions, suggests that the Moon could still be shrinking today. As it does, it is experiencing moonquakes along those thrust faults, with the rock shaking at the cliffs.

Scientists compare the process to the way a grape will gradually wrinkle up, adding lines as it cools and shrinks. But unlike a grape's skin, the crust around the Moon cannot stretch and is instead brittle, making it break apart as the shrinking happens.

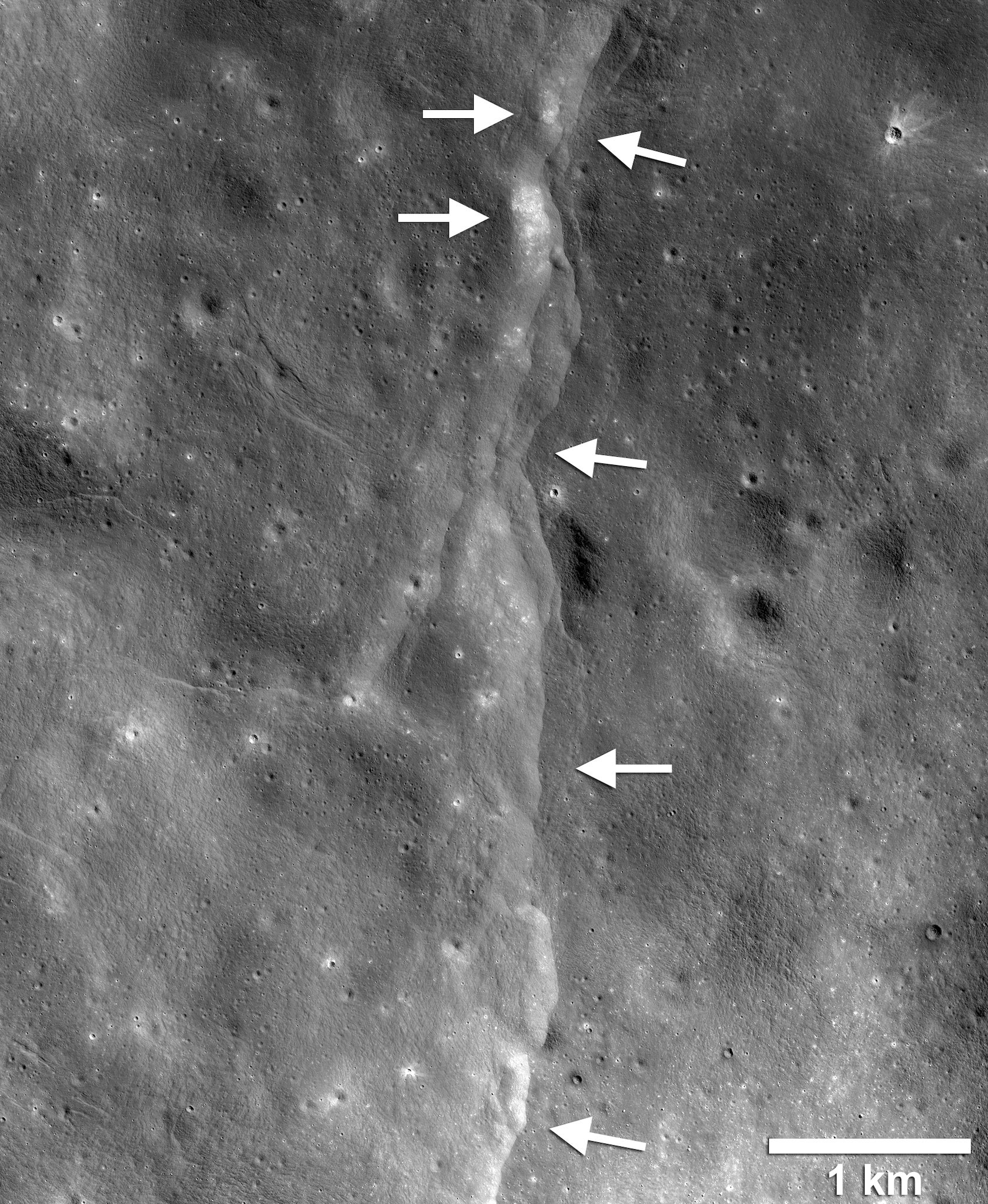

The faults form when the crust moves around, and one part of the crust is pushed up over another. They form unusual-looking cliffs that can be seen from the surface, standing tall and many miles long.

The new research was made possible by the creation of an algorithm that processed seismic data that was taken in the 1960s and 1970s. It helped shed new light on those moonquakes, including allowing for a better understanding of where they are actually coming from.

Once that location data was generated, it could be laid on top of the images of the thrust faults that were taken from a 2010 study that used pictures from Nasa's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Comparing the two, they found that at least eight of the rumbles were coming from movement of plates beneath the Moon's surface, not from asteroid impacts or other explanations. That helped confirm that the Moon is still experiencing true tectonic activity, according to the new paper published in Nature Geoscience.

The instruments left by Apollo astronauts in the past finished their work in 1977. But scientists think this shaking and shrinking is still happening to this day, with images seeming to show evidence of recent movement, such as boulders and landslides that appear to have recently fallen over.

"We found that a number of the quakes recorded in the Apollo data happened very close to the faults seen in the LRO imagery," said Nicholas Schmerr, an assistant professor of geology at the University of Maryland, in a statement.

"It's quite likely that the faults are still active today. You don't often get to see active tectonics anywhere but Earth, so it's very exciting to think these faults may still be producing moonquakes."

The seismic data was taken from instruments that astronauts dropped onto the surface during Apollo missions. The one left by Apollo 11 died after a few weeks – but the rest kept measuring, eventually picking up 28 different, shallow moonquakes between 1969 and 1977.

Of those quakes, eight were picked up near to the faults that could be seen in images of the Moon's surface. That led them to conclude the two were connected.

What's more, most of the shakes happened when the Moon was at the point of its orbit furthest away from the Earth. That happens because the stress from Earth's gravity disrupts its crust.

"We think it's very likely that these eight quakes were produced by faults slipping as stress built up when the lunar crust was compressed by global contraction and tidal forces, indicating that the Apollo seismometers recorded the shrinking moon and the moon is still tectonically active," said Thomas Watters, lead author of the research paper and senior scientist in the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

Scientists now hope to return to the Moon and learn more about what is happening to it. The Trump administration has ordered Nasa to head back as soon as it can, and hopes to have astronauts back on its surface in five years.

"For me, these findings emphasize that we need to go back to the moon," Schmerr said. "We learned a lot from the Apollo missions, but they really only scratched the surface. With a larger network of modern seismometers, we could make huge strides in our understanding of the moon's geology.

"This provides some very promising low-hanging fruit for science on a future mission to the moon."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks