Ministry of Sound takes on Spotify in legal battle

Dance music brand claims that playlists created by Spotify's users infringe the copyright of the label's compilation albums.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Can music fans be sued for compiling a playlist of their favourite songs? In what promises to be a landmark legal case, the Ministry of Sound is suing Spotify for alleged copyright infringement to prevent users of the streaming service replicating the playlists of its dance compilation albums.

Entertainment group Ministry of Sound has applied to the High Court for an injunction that would force Spotify to delete playlists compiled by users which “copy” the track listing and sequencing of the record label’s hit compilations. Ministry of Sound is also seeking costs and damages.

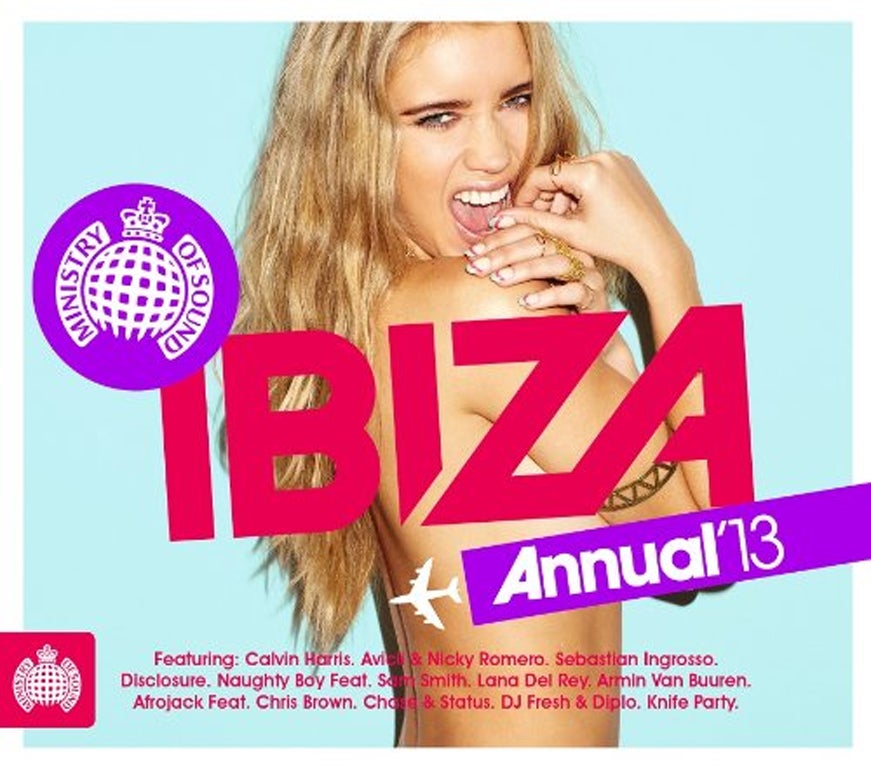

Sales of compilations such as The Sound Of Dubstep Classics and Ibiza Annual 2013 are booming. But whilst the individual tracks contained on the albums are licensed by their record companies to Spotify, the Swedish music platform which boasts a catalogue of 20 million songs, the branded Ministry compilations are not.

Lohan Presencer, chief executive of Ministry of Sound, the London nightclub opened in 1991, which then expanded into recorded music, called on Spotify to take down users’ playlists which directly mirror the track-list and running order of the Ministry albums and include the title “Ministry of Sound”.

Presencer argued that “a lot of research goes into” curating the compilations. “What we do is a lot more than putting playlists together,” he said. “The value and creativity in our compilations are self-evident. It’s not appropriate for someone to just cut and paste them.”

Spotify has rejected Ministry’s demands, pursued in a series of legal letters. The Swedish-based music service, launched in 2008 and which has 24 million users, last month launched a “browse” feature to encourage music fans to discover and share their own playlists.

Spotify, which has sought to negotiate a licensing deal with Ministry for four years, declined to comment on the action.

But a spokesman said: “Spotify’s goal is to grow a service which people love and ultimately want to pay for. Every single time a track is played on Spotify, rightsholders are paid - and every track played on Spotify is played under a full license from the owners of that track. We want to help artists connect with their fans, find new audiences, grow their fan base and make a living from the music we all love.”

The case rests on whether the order in which particular songs are sequenced – rather than the songs themselves – is protected by intellectual property law.

If the Ministry is successful, the ruling could have wider implications. A club DJ, whose living is based on mixing together a unique sequence of tracks, could injunct a rival who copied the same setlist.

A radio station, operating a commercially successful playlist, could sue a rival for playing the same songs in the same order.

The Ministry cited as precedent a 2010 High Court ruling which found that the fixture lists for the English and Scottish football leagues were copyright protected.

But the US courts threw out a comparable digital infringement claim. Marvel comics sued the makers of the City of Heroes online computer game because it allowed players to imitate the characters owned by Marvel. The judge described Marvels claims as “false and sham”.

Jim Killock, director of the Open Rights Group, who campaigns for digital freedom, said: “It’s vital that Spotify is able to provide users with the opportunity to make their own playlists. But if those playlists are then proven to have violated copyright they should be taken down.”

The best-selling Now! compilation series is available on Spotify, although the brand’s owners, Universal and Sony are both minority shareholders in Spotify.

The Ministry of Sound, founded by James Palumbo, the entrepreneur who has donated a reported £700,000 to the Liberal Democrats and was appointed a peer by the party last month, has sold more than 50 million compilation albums.

Ministry’s albums and singles enjoy huge download sales on iTunes. Spotify, founded to provide a legal alternative to web piracy, argues that streaming tracks does not “cannibalise” paid-for downloads.

The Ministry action follows the decision by Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke to pull his Atoms For Peace side-project from Spotify after complaining that the service, which has yet to post a profit, did not pay sufficient royalties to new artists. Spotify, which offers unlimited access to its catalogue for £10 a month, currently has around 6 million paying subscribers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments