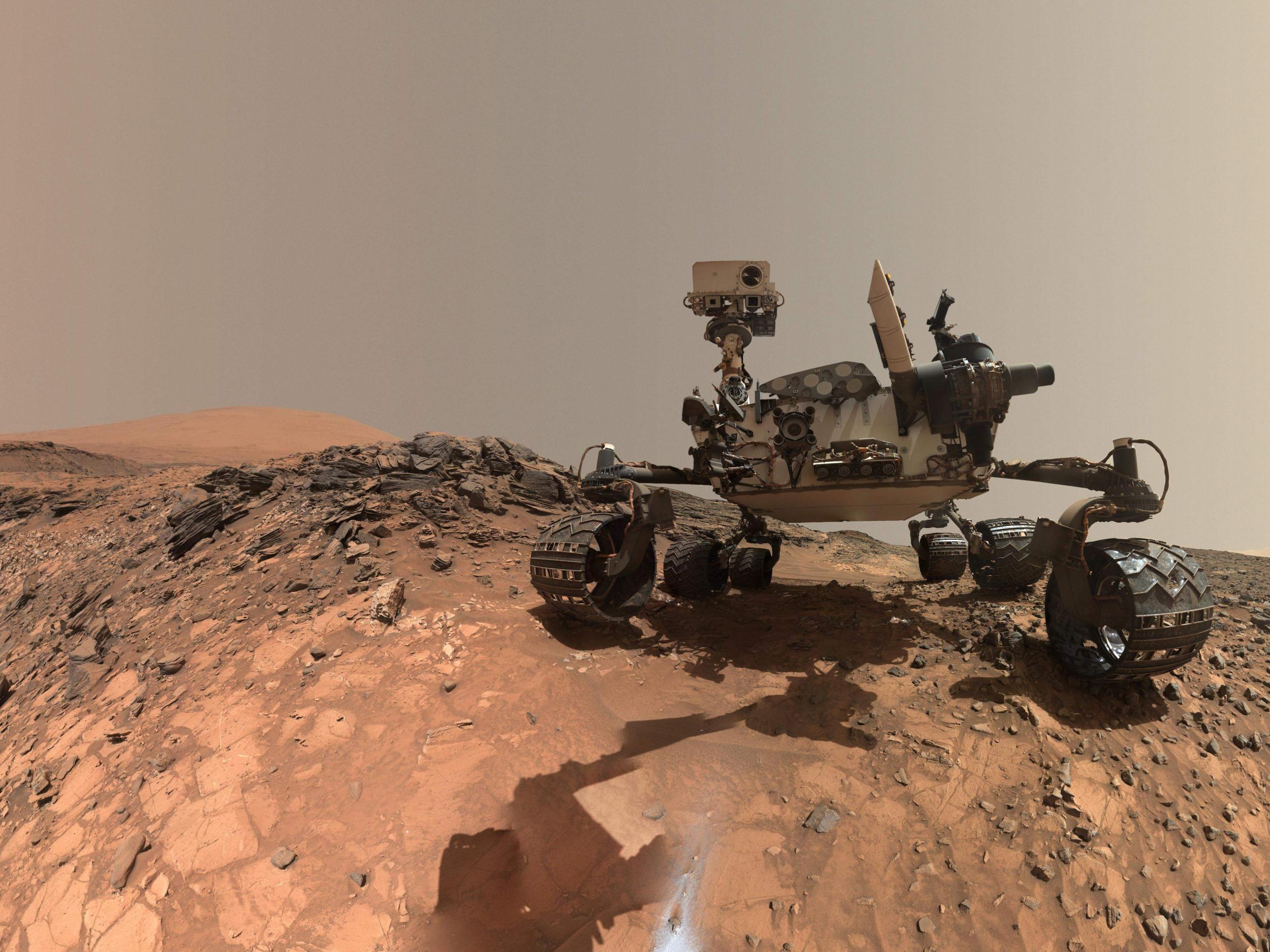

Mars is more porous than we thought, Nasa's Curiosity rover finds in breakthrough study

Scientists used similar instruments to those found in a smartphone to analyse the red planet's surface

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mars is more porous and less compacted than we thought, scientists have found in a breakthrough study that used data from Nasa's Curiosity rover in unusual ways.

The researchers used non-science engineering data to understand the red planet's surface and measure how dense the rocks are in the 96-mile-wide Gale Crater.

The discovery is not only a breakthrough in our understanding of Mars's surface, but gives researchers studying it a brand new way of exploring the planet as the Curiosity rover continues to drive around on it.

Scientists made the discovery by taking data from engineering sensors that are on board Curiosity. They are accelerometers and gyroscopes, of the kind used to tell a smartphone where it is pointing.

Curiosity's sensor also allow it to understand how it is orientated and where it is moving, with a great deal of precision, allowing its engineers to track it as it moves across the Martian surface.

When the rover is standing still, however, those same sensors measure the gravity at that spot. That meant the scientists could take all of those different pieces of data – related to 700 different places in all – and combine them to understand the gravity on the surface.

As the rover started to climb up a hill on the surface, the amount of gravity went up. But it did not go up as much as expected.

"The lower levels of Mount Sharp are surprisingly porous," says lead author Kevin Lewis of Johns Hopkins University. "We know the bottom layers of the mountain were buried over time. That compacts them, making them denser. But this finding suggests they weren't buried by as much material as we thought."

Scientists could use the findings to help understand where places like Mount Sharp came from, and how the Martian surface developed.

"There are still many questions about how Mount Sharp developed, but this paper adds an important piece to the puzzle," said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which manages the mission. "I'm thrilled that creative scientists and engineers are still finding innovative ways to make new scientific discoveries with the rover.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments