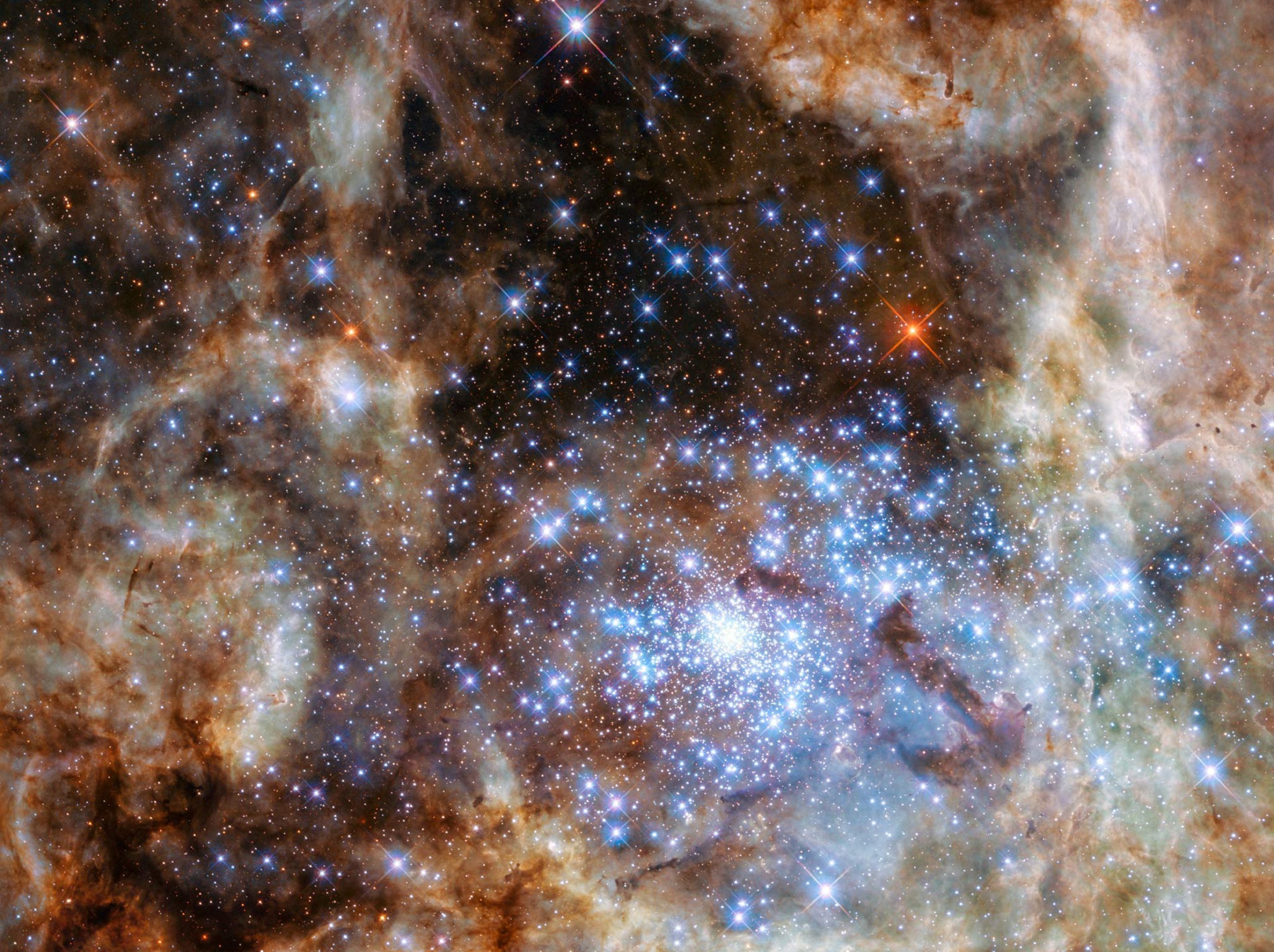

Huge stars, 30 million times brighter than the sun, spotted by Hubble Space Telescope

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are nine massive stars, together 30 million times brighter than our sun, sitting out in the universe.

A team of astronomers spotted a cluster of stars about 170,000 light years from Earth. Together they are the largest group of very massive stars ever spotted, and were seen through the Hubble Space Telescope.

The new find could bring new findings about how huge stars develop. Scientists also said that it was a worthwhile demonstration of the powers of the Hubble Space Telescope, which is ageing and is less powerful than new telescopes that are to be launched in coming years.

The cluster is just a few light years a cross, and sits in a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. But in that relatively small space is a huge range of massive, hot and luminous stars spitting out huge amounts of ultra violet light.

The nine stars — 100 times as large as our sun — are just the brightest of a huge group of stars.

None of the stars identified have unseated R126a1, also in the Tarantula Nebula, as the most massive star in the known universe at more than 250 solar masses.

Professor Paul Crowther, from Sheffield University's Department of Physics and Astronomy, showed with his international team in 2010 the existence of four stars within R136, each more than 150 times the mass of the Sun.

At that time, the extreme properties of these stars came as a surprise as they exceeded the upper-mass limit for stars that was generally accepted at the time.

Now, the team's new research has shown there are five more stars with more than 100 solar masses in R136, raising many new questions about the formation of massive stars as the origin of these huge creations remains unclear.

Saida Caballero-Nieves, also from the university, said: "There have been suggestions that these monsters result from the merger of less extreme stars in close binary systems.

"From what we know about the frequency of massive mergers, this scenario can't account for all the really massive stars that we see in R136, so it would appear that such stars can originate from the star formation process."

Prof Crowther, lead author of the study, published in the monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, said: "Once again, our work demonstrates that, despite being in orbit for over 25 years, there are some areas of science for which Hubble is still uniquely capable."

The team combined images taken with the Wide Field Camera 3 on Hubble with the unprecedented ultraviolet spatial resolution of its Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS).

The professor said identifying individual stars in this crowded region of space was only possible because of Hubble and he praised the work done by astronauts who risked their lives in 2009 to repair the STIS.

He said the team is continuing to analyse the Hubble data, allowing them to search for close binary systems in R136 which could produce massive black hole binaries.

The professor said this could contribute to the study of gravitational waves - the ripples in space time which were predicted by Albert Einstein and became worldwide news last month when another team announced they had been detected.

Additional reporting by Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments