How a small rock on the moon changed everything we knew about our closest neighbour

While most people were concerned with the Cold War, some of the most important discoveries about our planet were happening hundreds of thousands of kilometres above their heads, writes Mick O'Hare

Lee Silver was excited, very excited. An Olympic athlete craves a gold medal, a Hollywood actor an Oscar. But Silver was a geologist and, as far as he was concerned, he held a far greater prize. In his hands was a rock, a rock that would forever change our understanding of our planet, of our solar system. Geologists had long speculated about the origins of our planet and its only satellite, but here was confirmation. The moon had once been part of the Earth. It was one of the greatest scientific discoveries of this or any age.

However boring those school lessons may seem, however repetitious the information your teachers are imparting, it really is worth paying attention. Just ask David Scott and Jim Irwin, pupils in the geology classes of Professor Silver. Fifty years ago this month Scott and Irwin found what has since been dubbed the Genesis Rock.

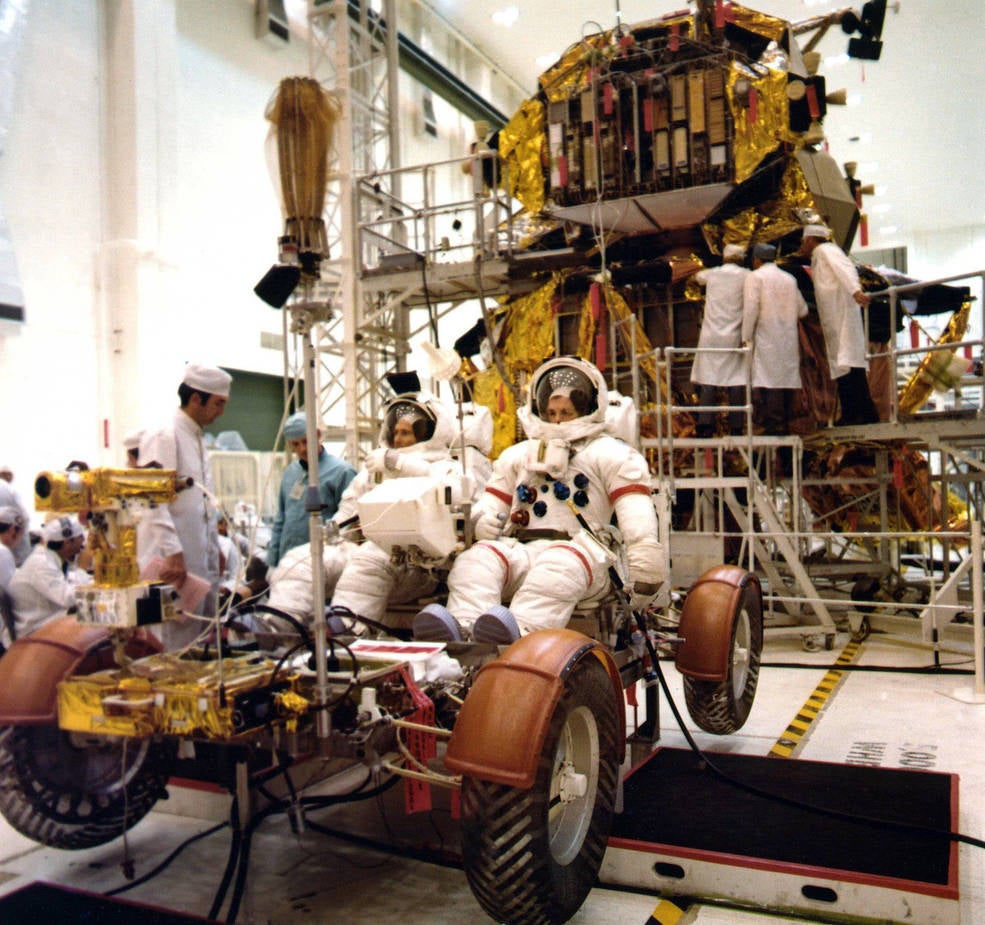

And what made their discovery even more august, was that the two were astronauts on Apollo 15, the fourth mission to land humans on the moon. Scott and Irwin weren’t scientists, they were US Air Force pilots recruited to Nasa’s Apollo astronaut corps, and before they were selected to fly on Apollo 15 wouldn’t have been able to tell moonrock from green cheese. But Nasa figured it was easier to train astronauts to be scientists, than it was to train scientists to be astronauts. And so they got sent back to school to learn everything from astrophysics to spectrometry. And, not least, geology.

The previous Apollo missions had all been about the achievement of putting a human on the moon. Apollo 15 was different, dubbed a J Mission (mission designations had begun at A. The first moon landing – Apollo 11 – was a G mission and now we’d reached J or, in Nasa’s words: “Extensive scientific investigation of Moon on lunar surface and from lunar orbit.”). It would be the first to have science at its core. “The propaganda benefits of being first on the moon had dissipated,” says Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo spacecraft collection at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. “Now the scientists at Nasa wanted their interests to take precedence.”

Public interest in the Apollo programme had waned since Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon in July 1969, and the three subsequent missions had all essentially been repeat acts with astronauts spending a brief time on the lunar surface before returning to Earth. Questions were being asked in Congress about the financial cost to the nation now that the US had “won” the space race against its Soviet Union rival. “Apollo was always a tradeoff between budget and benefits to America,” says Muir-Harmony. Future missions had already been postponed or cancelled and Nasa wanted to show the nation why going to the moon was still a worthwhile exercise as more earthbound problems such as Vietnam and the civil rights movement were exercising the minds of the American public. “Politicians had little interest in the science of the moon and nor, very much, did voters,” adds Muir-Harmony, “but Nasa at least wanted to show that it had a purpose in continuing with Apollo.”

I thought geology should be the main focus of the science we’d do on the moon but enthusing the technical guys at Nasa wasn’t easy

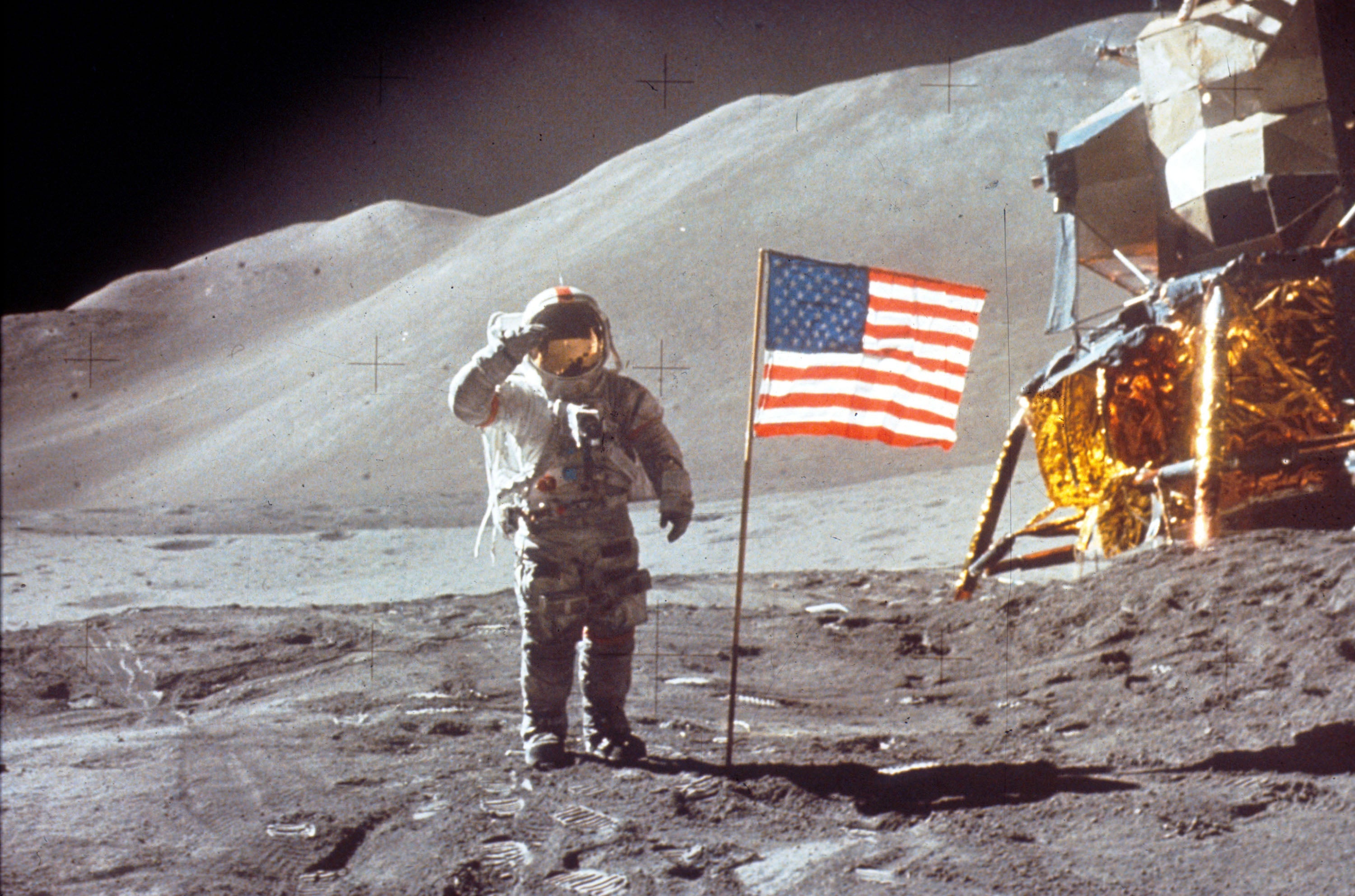

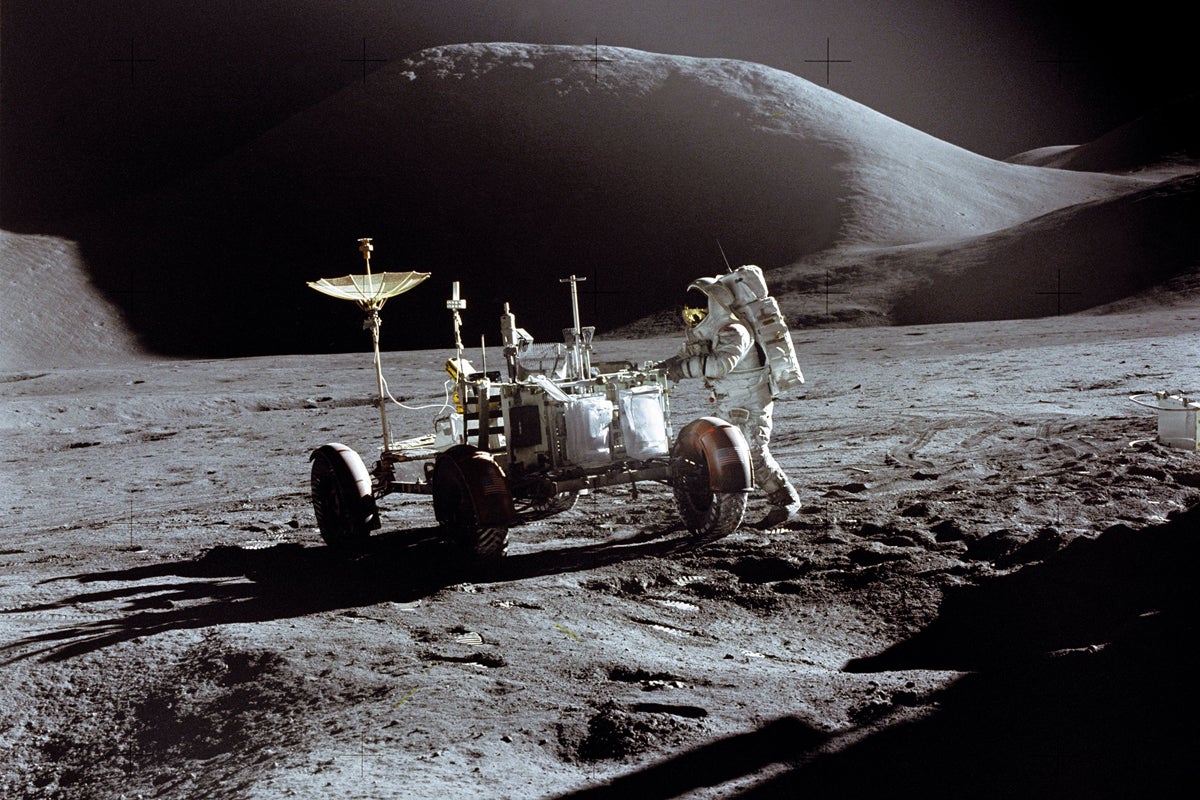

Apollo 15 touched down on the moon on 30 July 1971 and would remain there for more than three days. It would deploy the battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) – or “moon buggy” as it was nicknamed by the press – allowing the astronauts to travel greater distances from Falcon, their Lunar Module. For the first time the mission had a purpose beyond any propaganda value and, crucially, would be strikingly telegenic. TV cameras would be mounted on the LRV and were capable of broadcasting in colour – Apollo 11 had been broadcast to the world in monochrome. There were some concerns that maybe the LRV would not be fully operational because the timeline for its development had been tight and its design was, in many respects, down to guesswork – nobody knew exactly how it might perform on the moon’s surface. In the end it operated as it should, covering almost 30 kilometres at a maximum speed of 12 kilometres per hour and even surviving a minor hitch on the first day when the front-wheel steering failed. Fortunately it was quickly rectified.

The moon’s lower gravity meant the LRV rocked and rolled, kicking up huge plumes of surface dust. Irwin jokingly described Scott’s handling as “erratic” although the latter insisted he was avoiding rocks and craters that could have damaged the buggy. “The LRV, despite looking bouncy and unsteady, operated perfectly,” says Muir-Harmony. “It’s a pity it had to be left behind.” It’s still there, of course, along with two other LRVs used on the last two Apollo missions 16 and 17.

The mission achieved its scientific objectives. Despite their air force backgrounds Scott – the mission commander – and Irwin had proved to be willing science students. “They didn’t simply follow instructions,” adds Muir-Harmony, “they became scientists themselves.” Especially for TV audiences they proved Italian mathematician Galileo had been correct almost 400 years previously when he posited that objects fall at the same rate in a vacuum. Scott dropped a hammer and a feather (appositely taken from a falcon) at the same time and watched as, thanks to the absence of atmospheric drag, they struck the surface together. They were also the first astronauts to truly sleep on the moon, rather than merely nap (“Earplugs helped,” adds Muir-Harmony), giving physiologists the chance to study circadian rhythms on another planetary body. They drilled down through the moon’s surface to see what might be extracted, bagged up soil samples, ran experiments to study the solar wind, ran seismic and spectrometry studies and even released a satellite into lunar orbit to map the moon’s gravity field and measure plasma and particle intensities in space. But it would be while out on the LRV surveying Spur Crater, five kilometres from their landing site, that their newly gleaned scientific training would come to the fore.

Scott especially had found Lee Silver’s geology lessons fascinating. “I’d long been interested in archaeology and history,” he says. “And I was intrigued by the British explorers James Cook and Robert Scott who had made science a key focus of their journeys.” In tribute Apollo 11’s Command Module was named Endeavour – the British English spelling – after Cook’s ship. “The geology training for Apollo 15 was more extensive than for any other mission,” says Muir-Harmony. “David Scott spent a third of his training on geology alone and he and Irwin took field trips at least once a month from 1970 onwards. Scott’s wife even took a geology course so she could test him over dinner.”

Scott continues: “Geology seemed somehow an extension of those interests of mine. Lee was an inspiring teacher. I loved the field trips to Hawaii and Arizona – we even practised collecting samples while wearing space suits – and the art of interpreting millions of years through different rock samples. I thought geology should be the main focus of the science we’d do on the moon but enthusing the technical guys at Nasa wasn’t easy.” Deke Slayton was director of flight crew operations, one key role of which was ensuring the spacecraft was as light as possible. Weight was a crucial issue – for every extra kilo it weighed, more fuel would be required, an almost vicious circle. Even the number of plasters in the first aid kit was restricted. “So trying to explain to Deke why I needed a geological rake was like pushing water uphill,” explains Scott. “His attitude was once you’ve seen one rock, you’ve seen ’em all.” How wrong that would prove to be.

When Falcon first touched down at Hadley Rille on the edge of Mare Imbrium, Scott had stood peering through the lander’s top hatch explaining to Mission Control and the listening geologists what he could see and the traverses he intended to make in the LRV. “His descriptions were as good as any professional geologist,” said Nasa geophysicist Robin Brett. Hadley Rille had been specifically chosen because the geology was considered potentially productive and intriguing. After a detailed commentary on the mountains, ridges and craters, with some prescience Scott declared: “Tell those geologists in the back room to get ready because we’ve really got something for them.”

They certainly had. On the second day of their mission the LRV was heading towards the 4,500-metre-high Mons Hadley Delta and nearby Spur Crater. Just before they reached it, the astronauts spotted a boulder with a greenish tinge which they thought might prove interesting. But while approaching it the LRV began to run into soft soil, its wheels sinking and spinning. Irwin later said that they were starting to feel concerned. “We weren’t moving, and the terrain was steep,” he said. At one point he climbed out and grabbed the LRV to stop it sliding into a crater.

As with every potentially dangerous situation on the moon there was a protocol in place if the LRV was irretrievably damaged or stuck while out on a traverse. Gyroscopes on each wheel, set before departure, provided information on exactly where Falcon would be if they needed to walk in straight line back to safety. If they failed the alternative was to follow the buggy tracks, but that would take much longer. “Oxygen would be limited so we needed to always know where we were,” explains Scott. “The horizon is only one kilometre away on the moon so we quickly lost sight of Falcon. And the moon has no magnetic field so we had to use a sun compass, effectively a sundial, to orient ourselves by using the position of the sun at any given time.”

It was, without question, the most important discovery made on the Apollo missions

Fortunately the recovery protocol wasn’t required, Scott was able to reverse the LRV (it was so light on the moon – a mere 36 kilos – that the astronauts could drag it too) and after bagging a sample of the boulder – it would later turn out to be olivine – set off again for Spur Crater. “I can still taste the excitement of what we discovered there,” says Scott. As they stood on the rim of a 50-metre-deep gouge in the lunar surface, bright crystals reflecting in the sunlight caught Irwin’s eye. “Oh, man,” he exclaimed. A small white rock was standing out against the surrounding grey. The reflection was coming from white crystals on the rock’s surface. “Crystalline rock, huh,” said Irwin. “I think we might have ourselves something close to anorthosite,” replied Scott.

In his book Apollo’s Legacy, former chief historian of Nasa Roger Launius wrote: “The astronauts had discovered what they came for, a rock that might hold the answer to the question of the moon’s formation.” In the days after Apollo 15 returned, at a press conference a scientist referred to it in passing “as the ‘Genesis Rock’, a name that has stuck. Scientists had worked hard to ensure that the Apollo crews had the knowledge necessary to undertake useful work. To a surprising degree they succeeded. The astronauts had correctly recognised the importance of their discovery.”

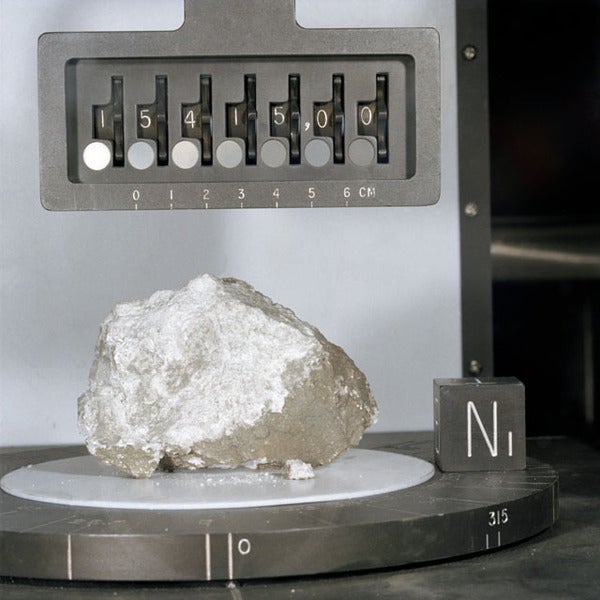

The rock’s official title is Sample 15415 and, as Scott correctly surmised, is anorthosite, a rock composed mainly of plagioclase feldspar. While the Earth was still solidifying the minerals that form anorthosite would have risen to float on top of the molten magma. But here was anorthosite on the lunar surface, 4.1 billion years old. There had long been debate between geologists about whether anorthosite would be found on the moon, but as Scott says: “Bang… there it was.”

Over time three competing theories had evolved regarding the formation of the Earth and its moon. The “sister theory” suggested the two were formed at the same time from the same cloud of gas and dust. The “spouse” theory suggested the moon was formed elsewhere and had been drawn into Earth’s orbit by the planet’s gravity. Meanwhile, the “daughter” theory – while perhaps seemingly more outlandish – suggested the moon and Earth were once a single mass with the moon splitting away from Earth soon after their formation.

This one rock narrowed the field dramatically, although it took geologists a few years to come to the conclusion after studying it. If the moon has significant amounts of anorthosite it too must have been made of molten magma, prompting the question as to where the energy to produce the magma came from. The smart money these days is on the idea that the Earth and Moon were once a single body with the debris that would form the Moon ejected into orbit most likely following a collision with another small planet around 4.5 billion years ago – the daughter theory.

The rocks of this proto-Moon would still have been in a semi-molten as a result hence the disparity in the dates of the Genesis Rock (4.1 billion years old) and the collision that ejected it because it took 0.4 billion years for the anorthosite to solidify. The olivine the astronauts found just minutes before the Genesis Rock also helped confirm the theory. Geologists had hoped that the landing zone would contain crystallised plagioclase feldspar and they’d briefed the astronauts on how to spot it. “Training and intuition enabled Scott to recognise the rock. Lee Silver’s classes proved their worth. It was, without question, the most important discovery made on the Apollo missions,” says Muir-Harmony. In fact, it vies for a place as one of the greatest scientific findings ever.

“It was in large part all down to Lee’s training,” explains Scott “He could explain complex stuff simply and make the geology of the moon – what looked to us like a grey lump – something important and wondrous and fascinating. He also taught us that, unlike on Earth, we couldn’t spend hours researching an area. It was get there, get back quickly, meaning we had to be taught to spot potentially important samples rapidly. To be honest when we spotted 15415 I have to admit I didn’t know just how important it was. But we both knew it was different. And so we took it. At the time I said, ‘I think we’ve found what we came for’z, which sounded prophetic, and was, but I didn’t realise the full story until it was analysed back on Earth. Without Lee, though, it wouldn’t have happened. All of the time on the moon I was thinking of the geology surrounding me.”

Those who criticise the moon landings from both left and right answer the question of whether its toil, trouble and especially the cost were worthwhile in the negative

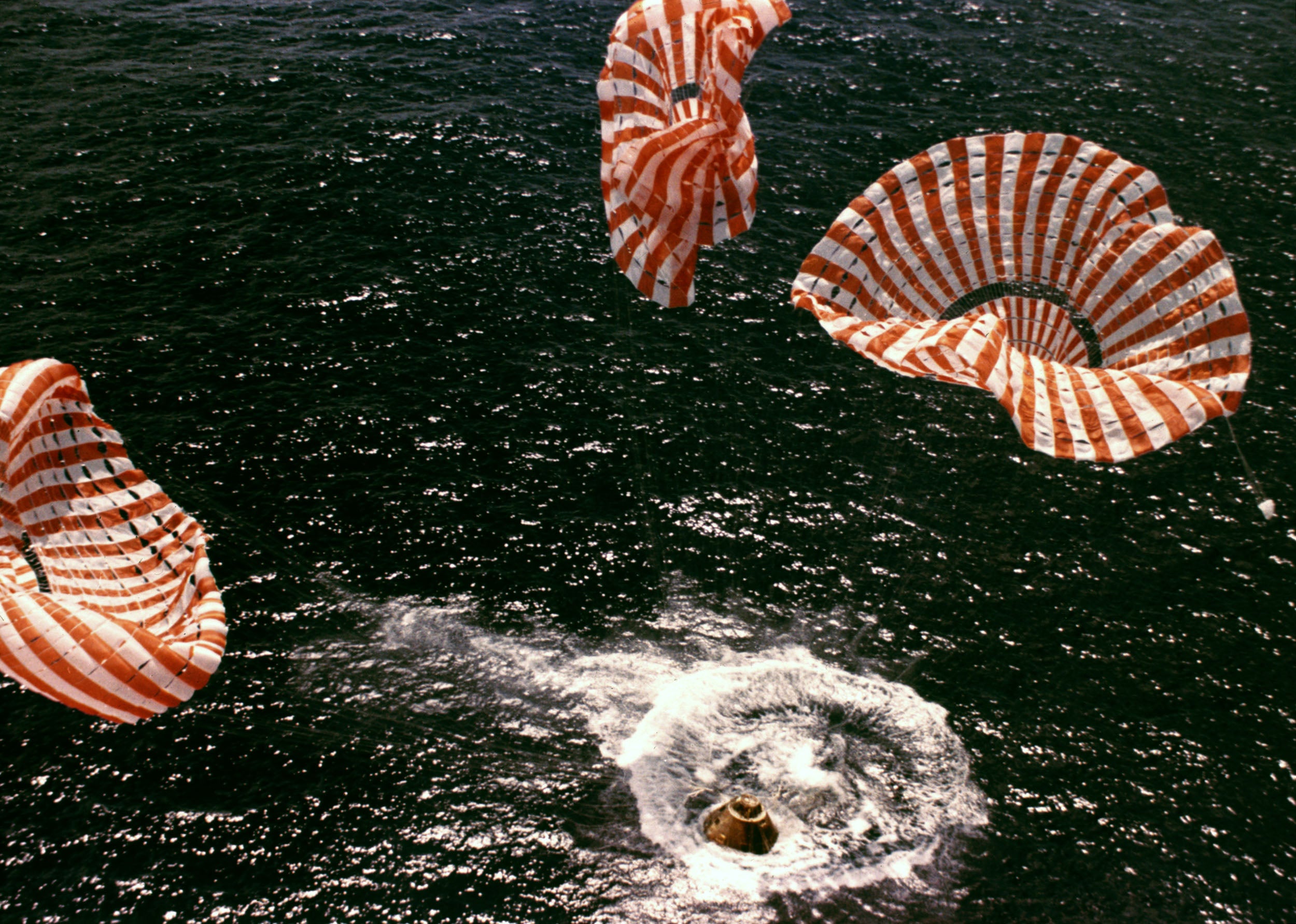

The astronauts were so enthralled with their discovery that Mission Control had to warn them their oxygen supplies were running low. Scott believed that Spur Crater may have revealed further geological treasures – he describes it as “a goldmine” – but it has not been visited since. The following evening Scott and Irwin lifted-off from Hadley Rille to rendezvous with their crew member Al Worden in the orbiting Command Module and to prepare for their return to Earth. But their scientific legacy was secured. Apollo 15 flight director Gerald Griffin later said: “Without doubt we witnessed the greatest day of scientific exploration ever seen in the space programme.”

“The story of the Genesis Rock was the high point in the science conducted on the moon,” says Launius. “And there was so much more. But whether this cut through with the public it’s difficult to gauge. The entire programme rested almost solely on Cold War rivalries and the US desire to demonstrate technological superiority to the world. Nonetheless, a great amount of scientific knowledge emerged from the missions. In many cases scientific textbooks were entirely rewritten to accord with what was discovered.”

David Baker, writing in the Nasa Moon Missions Operations Manual, said: “Of all the moon landings, Apollo 15 stands out for its pioneering work… it was the greatest of all the missions.” And it proved popular with TV audiences, not so much because of the astronauts’ extraordinary discoveries and scientific successes but because enhanced TV coverage showing the LRV scooting across the lunar surface, leaving tracks and kicking up dust, offered up such striking images. An unused version in Washington DC’s Air and Space Museum still receives far more attention than the Genesis Rock which now resides in the collection at the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility in Houston, Texas, inert and unaware of its significance in science history.

So was the Apollo programme revitalised in the eyes of the American public and, perhaps more importantly, the politicians who held the purse strings? “I’d like to say yes, but I’d have to say no,” says Muir-Harmony who has done much research into the politics behind the programme. “Visually it was arresting – astronauts driving around the moon picked up better TV ratings than any mission since Apollo 11, and the moonscape with mountains as high as Everest and deep canyons was impressive. And, of course, the science discoveries were truly breathtaking if one is at all interested in the history of the solar system. But if your sole focus is to get re-elected, then the economy, hospitals, education, and, back then, Vietnam were always going to be top of your agenda.”

So, in the long term, the political will to continue the programme ran out, with Nasa battling to maintain moon landings in the face of a sceptical public and Congress. The two camps grew further apart with Nasa pointing out the successes of Apollo 15 and the LRV while critics of the programme grew more shrill, some even suggesting that Scott was told by Nasa to announce that the astronauts had “found what we came for” in order to justify the scientific angles of the later missions and to keep the money flowing in. Scott usually replies: “Sure, and we were visited by aliens while we were there too.”

Apollo was always a balancing act between Cold War politics and money, with science a distant third. “Those who criticise the moon landings from both left and right answer the question of whether its toil, trouble, and especially the cost were worthwhile in the negative,” says Launius. “And it is fair to say that the moon landings were not predicated on the science. But look at what we would have lost if we’d never been.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments