How to create the perfect password: Use randomly generated poems

Two researchers at the University of Southern California recently published a paper with a novel solution for creating passwords that are both extremely hard to crack and relatively easy to remember

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first thing you learn when you try to create a good password is that your memory is pretty terrible. The second thing you might learn is that you're really bad at being random.

True randomness is hard to predict; humans aren't. Even if you're not one of the millions of people who use passwords such as “12345678” or “password”, you might still be making some amateur mistakes. For example, using a common phrase as your password, but then replacing the “i” with a “1”, or the “a” with an “@”, and so on. Or using common words and phrases, and putting the characters and numerals at the end of the password, instead of spaced randomly throughout. Or re-using passwords across sites, or not changing them often enough.

In short, basically any technique that would allow a human being to actually remember a password. OK, you say, but how do you possibly get around this? Any password that is going to be reasonably secure is also going to be impossible to remember. And any password you can possibly remember is probably going to be terrible. That's just the law of passwords, right?

As The Washington Post's opinion writer Alexandra Petri said recently, “The perfectly secure, perfectly memorable password is absolutely pure and rarer than the unicorn... That is to say, no one has ever found it, and some doubt whether it exists at all.”

But two researchers at the University of Southern California may have finally come up with the perfect solution. Marjan Ghazvininejad and Kevin Knight have recently published a paper with a novel solution for creating passwords that are both extremely hard to crack and relatively easy to remember: randomly generated poems.

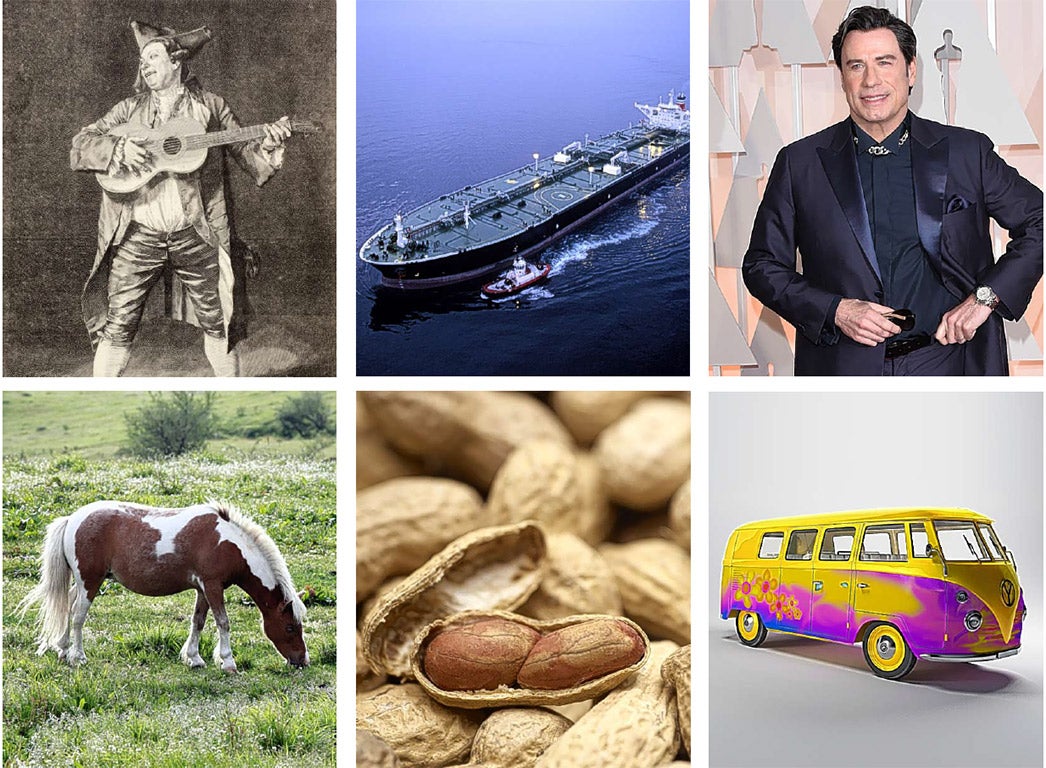

The inspiration for Ghazvininejad and Knight's study was actually a cartoon, created by Randall Munroe of the web comic Xkcd, which showed how a password made up of four random words – such as “correct horse battery staple” – is far more secure and a lot easier for people to remember than the typical jumble of random letters, numbers and symbols that most people think of as a secure password.

Munroe's point is that, even if you pick a fairly uncommon word, such as “troubadour”, and replace some of the letters with other symbols, this combination might only take a computer seconds, minutes or hours to guess. But a combination of four totally random words is both hard for a hacker to crack and easy for a person to remember: you can make up some weird little story about a horse correctly identifying a battery staple that will stick with you forever, unlike your co-workers' spouses' names, or the date of your anniversary.

The secret here is that those four random words are actually generated based on one very large random number. That random number is then broken up into segments, each of which corresponds with a word in the dictionary. It's basically a form of cryptography. To guess the full random number, a computer might have to test billions of billions of billions of possibilities before it hits on the right one, says Knight.

But while Munroe suggested using this large number to pick four random words, Ghazvininejad and Knight hit on the idea of using it to create a little poem.

In their paper, Ghazvininejad and Knight look at a few different methods for generating random passwords – the Xkcd method of using four random words, as well as a method of generating a random sentence – but they find that by far the most secure and the most memorable method is creating a short rhyming poem of random words.

As the researchers point out, humans have been using poetry as a way to remember information for thousands of years. It's no accident that long epics, such as the 12,000-line Odyssey, or the 17,000-line Canterbury Tales, were written using meter or rhyme. Most people today can't recite The Canterbury Tales, but they've still had certain sing-songy rhymes permanently burned into their memory – such as “Thirty days hath September”.

Ghazvininejad and Knight create their poems by assigning every word in a 327,868-word dictionary a distinct code. They then use a computer program to generate a very long random number, break that number up into pieces, and then translate those pieces into two short phrases. The computer program they use ensures that the two lines end in words that rhyme, and that the whole phrase is in iambic tetrameter, like so:

Receiver Mathew Halloween

deliver cousin magazine

These passwords might seem a little odd, but they're actually very, very secure. At current speeds, Knight estimates that cracking these passwords would take around five million years. By which point, we probably won't be using Facebook anymore.

If you read too many of these, they will make you feel a little crazy. But some of them are really fun to say:

The reigning Hagen journeyman

believers mini minivan

And teaches scripture bungalow

or celebrate or Idaho

Others are weird and evocative, hinting at wild stories just waiting to be made up as memory devices:

And British fiction engineer

Travolta captured bombardier

Australia juggernaut employed

the Daniel Lincoln asteroid

Enrique Hasbro Japanese

revealed aggressive amputees

Competing holy Hemingway

complies American ballet

A peanut never classified

expected branches citywide

The latest Union Rodeo

amounts of aiding dynamo

Ghazvininejad and Knight developed an online generator for these little poems, which you can try out for yourself (see details, below). They caution that this site is just for demonstration purposes – and that hackers could potentially download all of these poems and try them out, so they recommend that you view the site for inspiration rather than using its examples for your own password.

Obviously, remembering a little poem for every different password that you have might prove difficult, but the researchers suggest you could use one or two of these poem passwords for your most important accounts, or use one for your password manager, which will keep all of your other information secure. Many sites will ask you to add a special character or number to your password, but that shouldn't be too hard – you could just add some punctuation, or maybe replace spaces with a special character of your choosing.

The biggest drawback is that many sites these days limit the number of characters that you can use in your passwords, so these poems are probably too long for many of your accounts. But perhaps that will change someday soon. With various hacking stories having made headline news around the world in recent weeks, more and more sites are now considering dropping limiting the number of characters users can employ. Shorter passwords are a lot less secure, so it can pay to go with the flow.

© Washington Post. For examples of Knight and Ghazvininejad's passwords go to www.isi.edu/natural-language/people/poem/poem.php and keep refreshing the page

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments