Google users can now download their full search histories - and delete their archive

Amanda Hess delves deep into her online past - and is astonished by what she finds

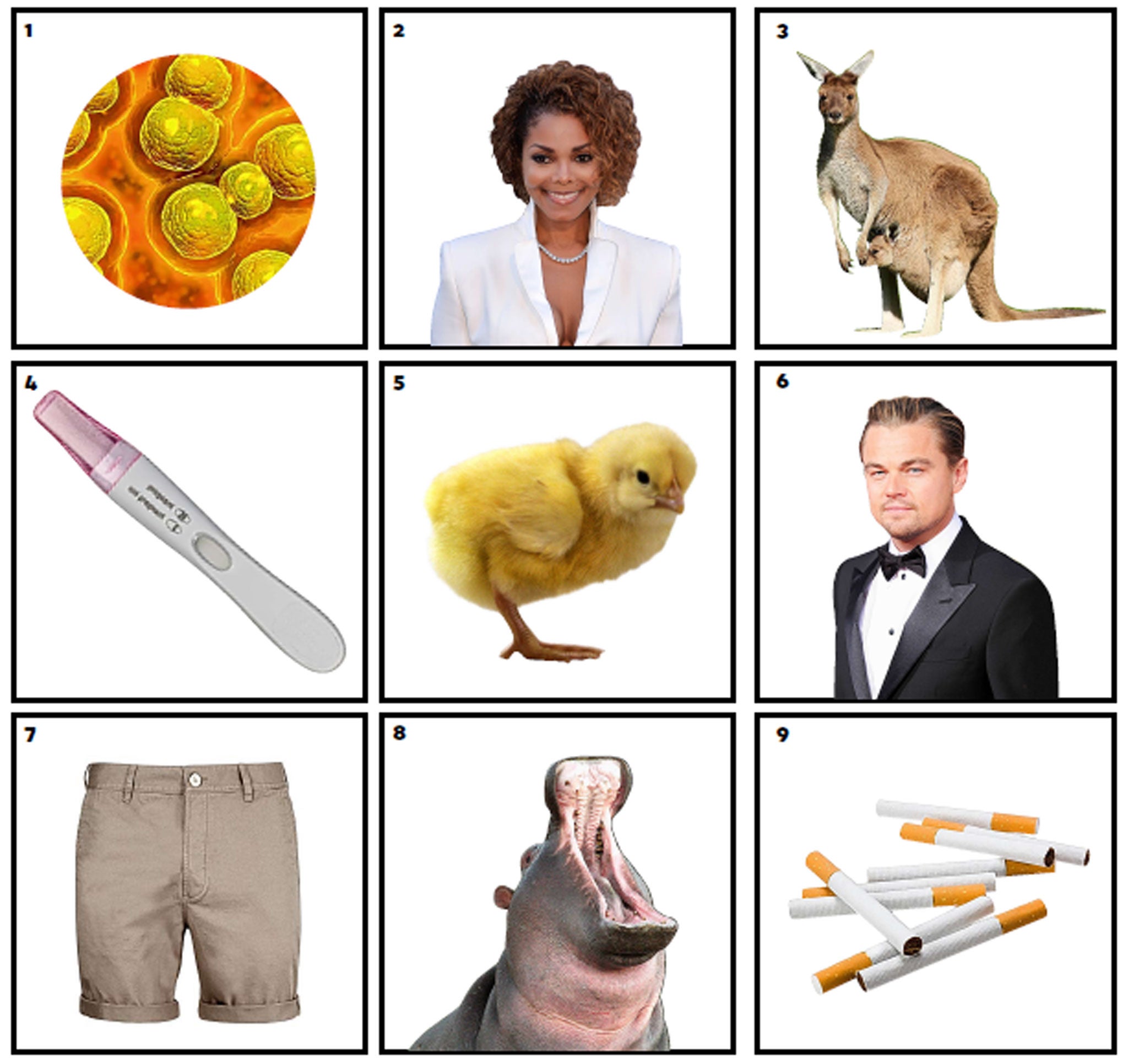

In 2006, I was mainly into Google for the cute stuff. Take one search session from October of that year, when I keyed in kitten, then sleeping dog, then leonardo dicaprio, then kitten with baby chick. Then kangaroo penis.

And then BIFURCATED PENIS, kangaroo VAGINA, bifurcated vagina, double vagina, kangaroo vagina again, animal vagina, and kangaroo penis. Finally, like some teenaged cliché who shoves his Playboy under the mattress when his mother walks in, I conjured a funny cat picture and then casually continued my browsing as if I hadn't just broadcast an interest in marsupial porn to the most powerful technology company in the world. I don't remember doing any of it.

Google has always profited from swiping its users' data but, in recent years, it's become a little bit more open about its collection practices and laid some of its cookies on the table. The Network Advertising Initiative, a "self-regulatory association" of digital ad companies that includes Google's ad outfit, DoubleClick, now gives internet users the option to opt out of certain types of monitoring. And Google now allows users to download their full Google search histories, dating back to the moment they created their accounts. From there, users can return to their regular Googling, or, if they want, delete their archive. Google introduces the feature with a stern warning that subtly winks at the consumer's newfound power over their own history: "Do not download your archive on public computers and ensure your archive is always under your control."

Choose to proceed, and Google spits all your searches back to you. My own history consists of 83,636 of them, each time-stamped down to the one-millionth of a second. It spans nine years of Googling, beginning when I was a 20-year-old student and stretching towards my thirties. The history excludes searches I conducted while signed out of my account, but it's certainly not lacking in material. The files arrive in the form of JavaScript Object Notation (or JSON) files, which are then crudely translated into a barely readable form: a mass of brackets, colons, underscores, 16-digit number strings, robotic gibberish, and somewhere in there, a weird thing you typed into Google six years ago. Such as kenny loggins girlfriend.

Advertisers may salivate over data like that, but parsing a Google search history is a tedious process for a human being. When US data journalist Mark Fahey dived into his own search history, he deemed his results "mundane". It turns out that "many people using Google are just trying to get to Facebook", and others are mainly asking Google Maps for help when they want to get away from the keyboard. But, at least on my feed, once you read past the logistical searches, there's a lot more where kangaroo penis came from. In the past decade, I've also Googled hippo penis, bonobo sex, every STD I can think of, and gruesome murder details. Which murder? Eh, just give me a grisly one.

Paging through my own history felt a little bit like preparing to defend myself in court. My mind flashed back to the murder trial of Casey Anthony, in which the prosecution combed through her computer search history and found a single chloroform query. (Meanwhile, I've Googled Casey Anthony eight times.) As I processed my results, I found myself making excuses for my own search behaviour. Hey, I Googled milk nymphos for work! Google has all the data it needs to know that I am a reluctant non-smoker (quit smoking depression how long does it last) who is sexually active (period five days late) and cursed with a fear of tiny holes (trypophobia). Tens of thousands of little disclosures like that risk coalescing into what law professor Paul Ohm calls "a database of ruin" just waiting to fall into the wrong hands and topple my reputation.

Still, Google doesn't want to ruin your life; it just wants to sell you out. One major category of searches that I like to call "Google, am I normal?" demonstrates why the search bar has become such a scintillating resource for advertisers. Typical ads work by trying to convince me that I need to buy a new product to solve a problem I didn't know I had: a luminous Andie MacDowell poses for an anti-ageing serum, and I search the mirror for fine lines. But for nearly a decade, I've been tipping Google off to all the real ailments and imagined insecurities that I already have, at a pace of about once an hour, every hour of the day: celebrity diet, pants are uncomfortable, migraine difficulty speaking, before and after plastic surgery, and worst cramps ever why.

Google promises not to tie your consumer profile to "sensitive" demographic descriptors such as your "race, religion, sexual orientation, or health" without your consent, but gender is one typically protected class Google doesn't mind exploiting. Besides, a recent study by two Irish researchers found that even without an explicit "gay" or "Christian" ID tag, "search engines learn quickly" about exactly who they're dealing with. Even when the user is previously unknown to Google, the engine begins to tailor its responses based on a number of "sensitive topics" in as few as three or four searches. And though Google is now inviting users to delete their search histories in a couple of clicks, it is very unclear what that means: the company's privacy policy still reserves the right to record your search results, tie them to your IP address or Google account, then target ads on Google properties and beyond.

Then there are all the other data miners loading my browser with cookies as I travel wherever a kangaroo penis search takes me. It's hard to know just how closely Google is tracking me, but BlueKai – a digital marketing giant that boasts one of the most comprehensive collections of third-party data scrubbed from all over the Web – allows users to look up their consumer profiles to see how they're sold to advertisers. And given the depth of the disclosures I've plugged into the net, I'm actually a little surprised that these digital ad companies don't seem to know more about me.

My BlueKai consumer profile correctly guesses that I'm an unmarried professional female flat-renter who buys hair products, make-up, deodorant, feminine products, and pizza. But the profile also pegs me as a 40-something woman interested in non-dairy milk, women's plus-sized clothing, luxury cruises, and empty-nest magazines. I am not that consumer (though I feel like we would be friends). All of my weird-body searching amounts to a vague insight that I may be interested in buying "ailment products". The company's most specific insight about me is that I probably buy dry pasta. Who squealed?

But beneath the crude demographic casting, there are truly personal insights hidden in my history if you know where to look. One of my more surprising finds is that my searches for women's names –celebrities, colleagues, characters – have far outpaced my search interest in men. Taken together, the history reads a bit like a slightly unhinged love letter to the women who have fascinated me throughout my life. When I was 21, they were fiona apple and janet jackson. At 22, artist jenny holzer and agent scully. At 25, feminist writer roxane gay, darlene conner, and then-power couple lindsay lohan samantha ronson. At 28, shonda rhimes and shiloh jolie-pitt. Other searches function like scraps pinned to a mood board, outlining the kind of woman I have wanted to be: cassandra's room wayne's world, robyn haircut, 70s boat woman, crystal castle she-ra, kristen stewart gifs, olive oyl president, elizabeth wandering through pemberley, short women, mean women, cool moms, condoleezza boots, katharine hepburn made husband change name, diane keaton in a bra.

"Imagine that someone has 40 years of your search history," Casey Oppenheim, co-founder of the online data protection app Disconnect, told New York Times readers last year of the risks of big data. It was meant to be a discomfiting prompt, but the idea excites me, too. Google searches are records of the lives we've lived, as taken from a peculiar vantage point that nevertheless defines the time in which we're living. Some searches read like diary entries and others like open letters to the hive mind.

Personally, I have some searches I'd rather not see saved for posterity: I can live with come to my window lyrics and zayn removes blonde streak, but what shellfish jews eat looks pretty bad, though not as bad as how to blow job, which is at least better than random house starting salary. The very worst thing I have ever Googled was my boyfriend's Klout [online social influence] score. When I die, please just tell my kids about the time I Googled carlos santana khaki shorts.

© Slate.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks