Some scientists want to hack the planet to cool it down – and the consequences could be extreme

Fleets of planes in the stratosphere, space mirrors and other geoengineering technologies offer a chance to reverse the worst effects of climate change. But might the cure be worse than the disease?

On a small Indonesian island in April 1815, a volcano changed the course of human history. The ‘super-colossal’ eruption of Mount Tambora was the most violent volcanic eruption ever recorded, blasting so much ash and debris into the upper atmosphere that it induced a period of global cooling known as the ‘Year Without a Summer’.

The volcano’s impact on Earth’s climate resulted in crop failures, famine and social unrest. Some historians have even attributed Napoleon’s loss at Waterloo to the two months of unseasonal rain that preceded the battle. Temperatures around the world dropped by an average of 3℃ for several years before the plume’s microparticles dissipated and the climate returned to pre-eruption levels.

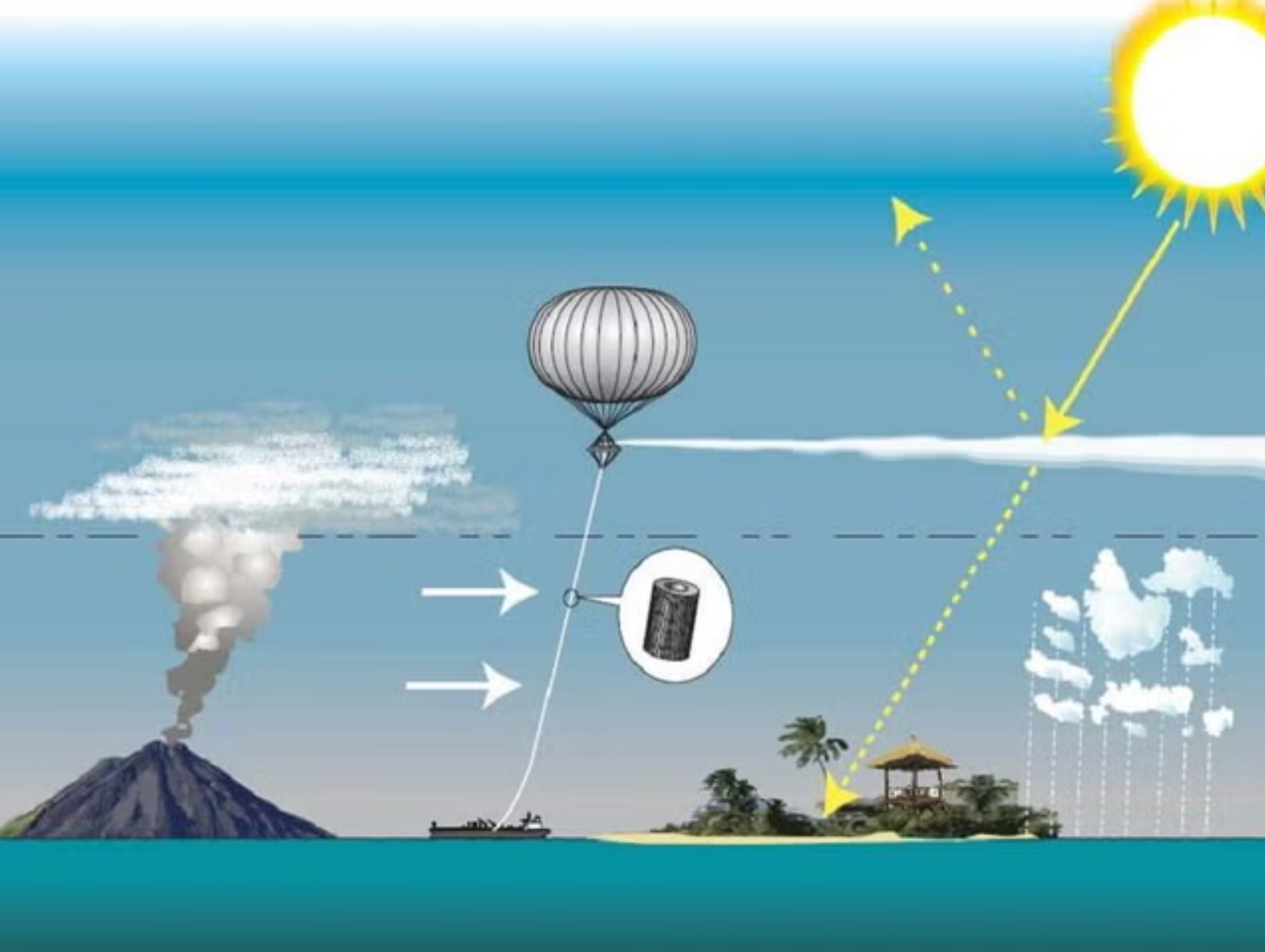

Now, 200 years later, some climate scientists are proposing a technique known as stratospheric aerosol injection that would artificially mimic the effects of a massive volcanic eruption. If successful, it could slow down, or even reverse, the worst effects of human-induced global warming.

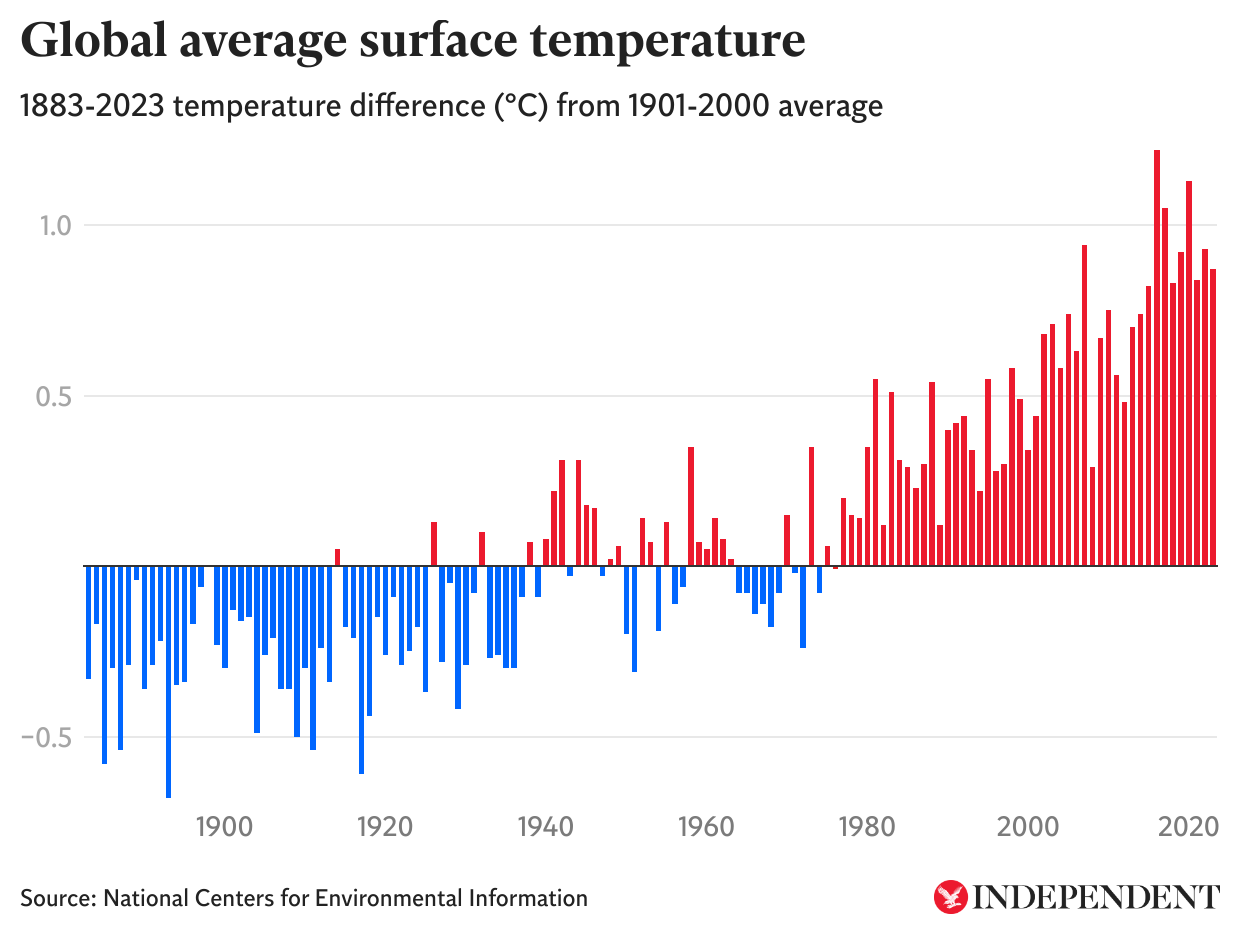

It is one of several forms of an increasingly popular field called solar geoengineering: essentially hacking the natural systems of our planet to cool it down. Record-breaking temperatures and rapidly-shrinking sea ice around Antarctica have led to fears that aggressive net zero targets alone may not be enough to prevent the planet heating above the critical 1.5℃ limit.

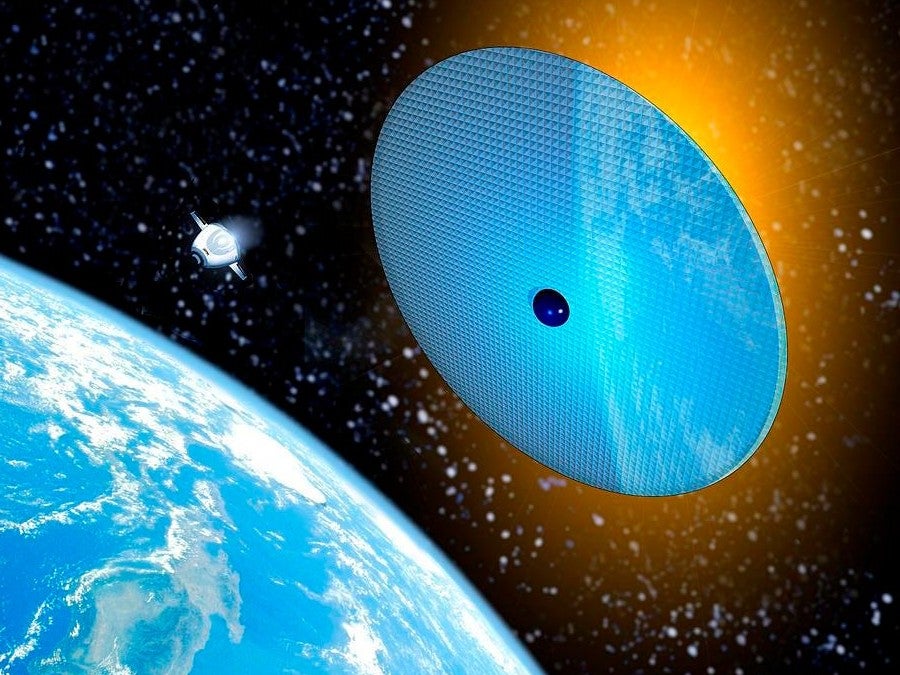

Other ideas to reflect solar radiation away from Earth range from vast mirror systems placed in orbit, to a giant space “umbrella” tethered to an asteroid. This latter technique was developed by István Szapudi, an astronomer at the University of Hawai’i Institute for Astronomy, who published a study this week outlining how such a system might work.

The method involves using a captured asteroid as a counterweight for the sunshade, which would make any such endeavour vastly cheaper than previous proposals for a space-based solar shield. Dr Szapudi tells The Independent that his design would reduce the weight of such a geoengineering project by around 100 times.

“Given the severity of the problem, any avenue worth exploring that might lead to the partial mitigation of a catastrophe should be investigated,” he says. “Even if we stopped emitting CO2 today, the levels would not go back, at least not immediately, to pre-industrial levels, thus some geoengineering might be necessary even in the optimal case when humanity gives up on fossil fuels in record time.”

Simulations suggest that reflecting just one per cent of sunlight back into space is enough to compensate for all the greenhouse gases released since the Industrial Revolution. Dr Szapudi estimates his technology would be capable of reducing solar radiation by up to 1.7 per cent, but warns it may take decades to implement.

All other space-based approaches remain theoretical, though they did gain mainstream attention in 2019 when US presidential hopeful Andrew Yang included “giant foldable space mirrors” as a “last resort” in his $5 trillion proposal to prevent a climate catastrophe.

The quickest and least expensive way of achieving the same effect as a space mirror is also the most controversial, involving the injection of chemicals into the Earth’s upper atmosphere. This could be achieved within months through fleets of aircraft or balloons pouring millions of tons of sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere – just like a giant ash cloud.

Estimates by Professor David Keith from the University of Chicago, who authored A Case for Climate Engineering, suggest this method would cost around $10 billion per year for the entire planet – roughly one 10 thousandth of global GDP.

Beyond the uncertain outcomes, one of the biggest drawbacks to this approach is that it only shields the Sun’s light rather than reducing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This means that if the stratosphere injections suddenly stopped it would result in “termination shock”, whereby all the catastrophic impacts of climate change occur simultaneously.

Authors of a 2018 UN climate report said this method should be used as a “remedial measure” to avoid an environmental catastrophe, however it remains hugely controversial due to the unknown consequences and the complete lack of international consensus on if or whether it should be implemented.

“It is far from clear that stratospheric sulphate injection will turn out to be scientifically viable, politically viable or ethically viable,” Stephen Gardiner, a professor of philosophy at the University of Washington and author of A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change, tells The Independent.

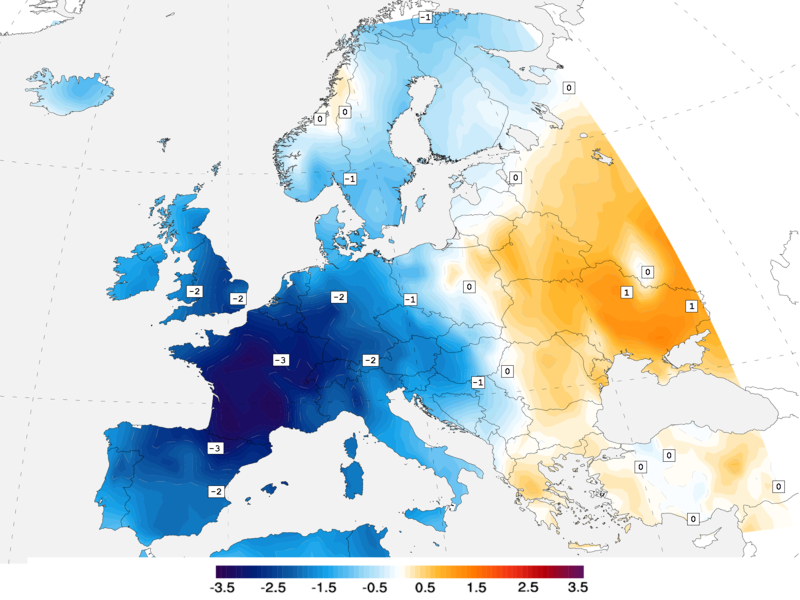

Professor Gardiner warns that the ethics of solar geoengineering “is one of speculation and desperation” and that it could be used as a tool for injustice and oppression to create mass famine, flooding and drought if deployed by malicious actors.

“I also worry about the possibility of a geoengineering arms race, where each country claims the right to defend itself against both climate change and the geoengineering interventions of other countries,” he says. “That could generate a nightmare scenario that is even worse than the climate impact geoengineers hope to prevent.”

Last year, hundreds of climate scientists and academics signed an open letter calling for an international non-use agreement on solar geoengineering. Signatories labelled it a “speculative and highly risky techno-promise”, warning that it distracted from international aims to reduce fossil fuel reliance. They urged the United Nations to send out a “strong political message”, though none is yet to materialise.

In February, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) released a report stating that such controversial measures may be humanity’s “only option”. The UNEP is now calling for a full-scale review into the technology and how a multinational framework could be governed.

Both pro- and anti-geoengineering scientists are united on this last part: the need for more research into the technology and the unintended consequences for the climate. These could range from disrupted monsoon seasons in India and China, to confused El Nino and Polar Vortex patterns, impacting billions of people and potentially resulting in far more social and climactic disorder than resulted from Tambora’s eruption.

Confined indoors by daily lightning storms during that Year Without Summer, Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein – a cautionary tale about man’s attempt to interfere with nature. The repercussions for Dr Frankenstein in creating literature’s most famous monster were difficult to predict. Scaling his impulse up to a global scale makes forecasting it virtually impossible – but that might not be enough to stop us from finding out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments