From floppy disks to Betamax, retro gadget fans are rejecting today's endless tech upgrade race

Whether they're using an old word processor, an ancient piece of musical gear or an ageing 1980s PC, these people simply don't want to do the bidding of an industry that requires us to jettison last year's products

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

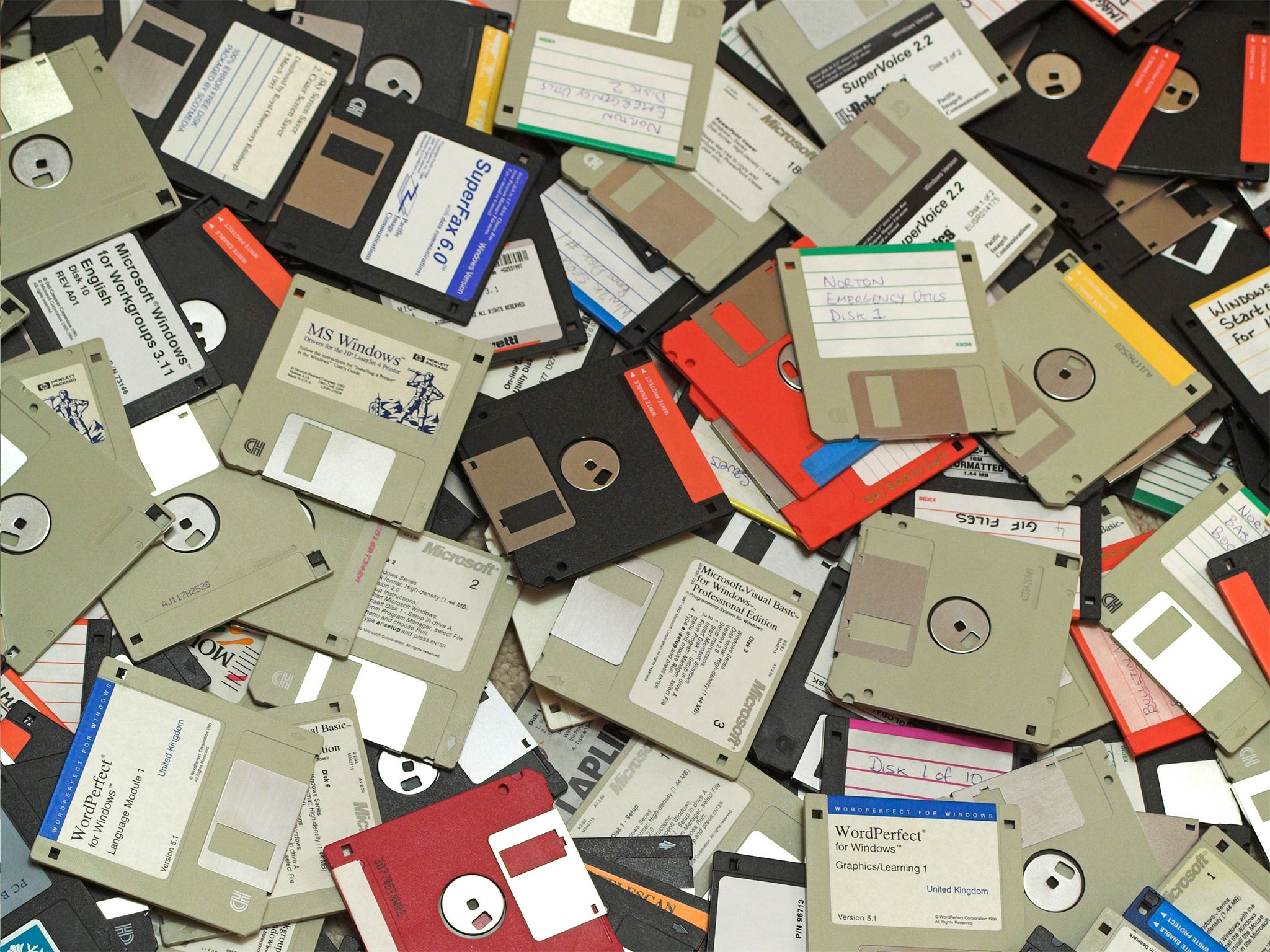

Your support makes all the difference.Towards the end of 2015, one of the last sources of floppy disks in the UK, Verbatim, quietly stopped production. There was no fanfare and no obituary. Maplin's product page for a pack of 10 Verbatim disks, each holding a mere 1.44MB of data (a fraction of the size of one MP3 file) simply states that the disks are now a "discontinued product", placing them alongside thousands of other pieces of technology that are phased out every year.

Yes, the floppy disk was already a relic of a bygone computing age, and its passing will have gone largely unnoticed – but for a dedicated group of people, this was a significant moment. Whether they're using an old word processor, an ancient piece of musical gear or an ageing 1980s PC, floppies still form part of their lives, and they'll now have to be sourced secondhand or overseas. These people simply don't want to do the bidding of an industry that requires us to jettison last year's products and buy new ones that are supposedly a bit better. Resisting that temptation to upgrade and sticking with technology that's deemed "old hat" feels almost heroic these days, whether it's down to sentimental attachment, retro fetishism or just a stubborn unwillingness to play the game.

"I probably straddle the first two categories, but yes, it's nigh on impossible to keep out of the upgrade loop," says writer Matthew Holness, best known for his horror author character Garth Marenghi. "If you try, you end up having this nagging sense of doom that it's all going to catch up with you." Holness, whose fondness for old tech extends from workbenches to coffee machines, chooses to write on a functionally limited device from more than a decade ago called an AlphaSmart Neo.

"It's been a saviour for me, as a writer," he says. "It's like an old word processor, and it was made for classrooms as an educational tool to help kids to type. You can't edit as you go along because the screen is too small, but it's perfect for bashing out rough drafts. And, of course, there are no distractions from the internet. It really forces me to write. When I found out they were being discontinued, I bought three."

Holness's love of his Neo is analogous to Stephen Sondheim and his Blackwing 602 pencils, or the ancient DOS machine running WordStar 4.0 that George RR Martin used to write the novels that eventually became Game of Thrones. These tools give a sense of security to their owners, enhancing their creativity and, at least in their opinion, doing the job far better than any modern equivalent. "Getting a laptop always felt like taking the easy way out," says Ben Jacobs, who made several albums under the alias Max Tundra on an old Commodore Amiga 500. "I wouldn't say I felt superior... but using newer technology always felt like taking a step back – even though making music with the Amiga involved typing endless columns of letters and numbers. Eventually, I fell out of love with it, but I felt very sad the day I sold it – not least because it didn't go for very much money. Someone in Denmark paid £20 for it."

We're often told that Apple is the world leader in producing technology that we feel an emotional connection to, but it's not the smartphones, computers or tablets that we feel affection for; these things are easily and regularly swapped out and upgraded, while the content – the thing we're really attached to – remains largely the same.

Alfonso Camisotti, who runs the Audio Centre in Croydon and has repaired old technology for more than 40 years, has observed a far stronger emotional bond between his customers and their tape machines, televisions and record players. "The people who come into the shop would rather keep things than throw them away," he says. "And I guess I'm one of the last of the Mohicans to appreciate quality machines. Take Betamax. Yes, VHS did the job and won the race, but it was an inferior system. People who know this come here from all over the UK to say, 'Look, I've got this machine, can you help me make it work?' That's what I do. And I get a real kick out of getting them working again."

The technology marketing machine likes to give the impression that everyone is using cutting-edge kit, but it's easy to forget our continuing attachment to old stuff that's probably deemed to be obsolete: old valve radios, Panasonic tape decks with XBS graphic equalisers, stacking 7in players, even DVD players that are now being usurped by the rise of Netflix. "I use a very old four-way mains socket extension," Ben Horsley, an independent creative director, says. "It's black, dirty and solid as a rock. The reason I keep it is because my dad gave it to me, and said: 'My dad gave this to me.'"

These things, by virtue of having lasted as long as they have, were evidently built to last, and Camisotti has seen the longevity of technology decrease as it gets smaller and smaller. "Something like an HDMI socket – if you move it, it snaps, and if it snaps you have to change the whole board," he says. "It's a really expensive way of doing things."

But it's by far the easiest. Swimming in the opposite direction to the technology industry is hard, especially when we're being bombarded with information about wireless audio streaming, 4K televisions and digital wallets. Try asking for a Scart cable in a high-street shop without raising an eyebrow, and listen for hoots of laughter if you explain you still occasionally use dial-up internet or your headphones are connected to a Discman hiding in your bag.

"These things don't feel cool," Holness says. "But they make my life more enjoyable. There's a pleasure in using things that people in general aren't going crazy for. It reminds me that I'm a person, that I'm an individual."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments