EU project aims to preserve old files for posterity

For computing's early-adopters, the phrase "floppy disk" probably conjures up images of a pile of plastic and metal now gathering dust in the back of a wardrobe. Though it may well be a few years since the machinery designed to play them was thrown out, thanks to a new project by researchers at the University of Portsmouth they may not necessarily be also consigned to the dustbin.

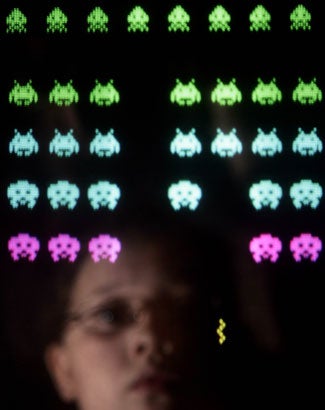

With the development of the world's first "general purpose emulator", researchers hope it will be possible to read all types of computer file, from the arcade machines of the 1970s to the floppy discs and minidiscs of more recent years. The emulator, which can recognise and play files previously held back by being tied to a particular and often outdated computer, is part of an EU project worth more than €4m designed to preserve digital files from the past which may otherwise have been lost.

Computer historians Dr David Anderson and Dr Janet Delve and computer games expert Dan Pinchbeck at the University of Portsmouth are partners in the project, entitled KEEP (Keeping Emulation Environments Portable), which aims to develop methods of safeguarding digital objects including text, sound and image files, multimedia documents, websites, databases and video games.

Dr Delve said: "People don't think twice about saving files digitally - from snapshots taken on a camera phone to national or regional archives. But every digital file risks being either lost by degrading or by the technology used to 'read' it disappearing altogether. Former generations have left a rich supply of books, letters and documents which tell us who they were, how they lived and what they discovered. There's a very real risk that we could bequeath a blank spot in history."

Every year a vast amount of new digital information is created - it has been estimated that in 2010 this will be equivalent to 18 million times the information contained in all the books ever written - and the rate of growth shows no sign of slowing. Britain's National Archive holds the equivalent of 580,000 encyclopaedias of information in file formats that are no longer commercially available; research by the British Library suggests Europe loses £2.7bn each year in business value because of difficulties in preserving and accessing old digital files.

Dr Anderson said: "We are facing a massive threat of the loss of digital information. It's a very real and worrying problem. Things that were created in the 1970s, 80s and 90s are vanishing fast and every year new technologies mean we face greater risk of losing material.

"Early hardware like games consoles and computers are already found in museums but if you can't show visitors what they did, by playing the software on them, it would be much the same as putting musical instruments on display but throwing away all the music. For future generations it would be a cultural catastrophe."

Researchers and those in charge of national archives globally have long been concerned about the threat of losing digital information.

Mr Pinchbeck said: "A vast bank of information needs to be catalogued and stored. Games particularly tend not to be archived because they are seen as disposable, pulp cultural artefacts, but they represent a really important part of our recent cultural history. Games are one of the biggest media formats on the planet and we must preserve them for future generations."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks