Cyber-crime thriller Blackhat used a former hacker to teach the cast to code

Mathematician and hacker Chris McKinlay seized the opportunity to help director Michael Mann achieve something film-makers often get really wrong

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Hollywood came calling, Chris McKinlay, a mathematician and hacker (the good sort) got excited. Michael Mann, the American director of The Last of the Mohicans, Ali and Heat, wanted him to work as a consultant on a big-budget cyber-crime thriller. McKinlay seized the opportunity to help him achieve something film-makers often get really wrong.

"I can't think of a movie that has been a realistic depiction of technology," McKinlay says from the University of Minnesota, where he is a postdoctoral scholar. What's the worst techy film he's seen? "Swordfish leaps to mind. In one scene the guy's tracking 64-bit encryption while getting a blowjob from the bad guy's girlfriend. It's like Fifty Shades of Grey piped into a bad tech movie."

McKinlay is as concerned about the realism of the culture and behaviour depicted in technology on film as he is the nuts and bytes themselves. Because for as long as cinema has existed, an industry that has embraced and advanced technology behind the camera has often struggled to realise it convincingly on screen. For directors who care, consultants are crucial and increasingly feature in the credits.

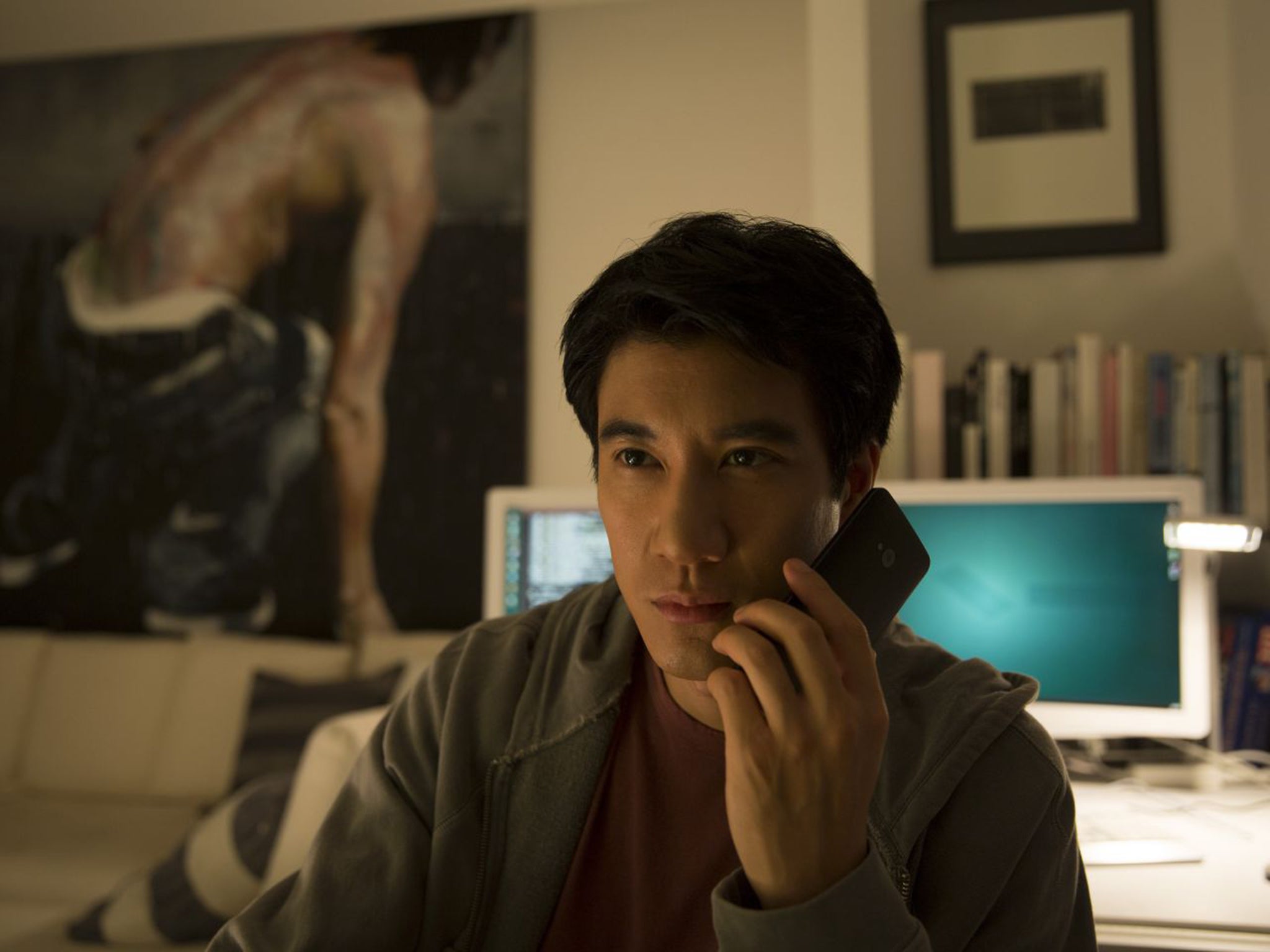

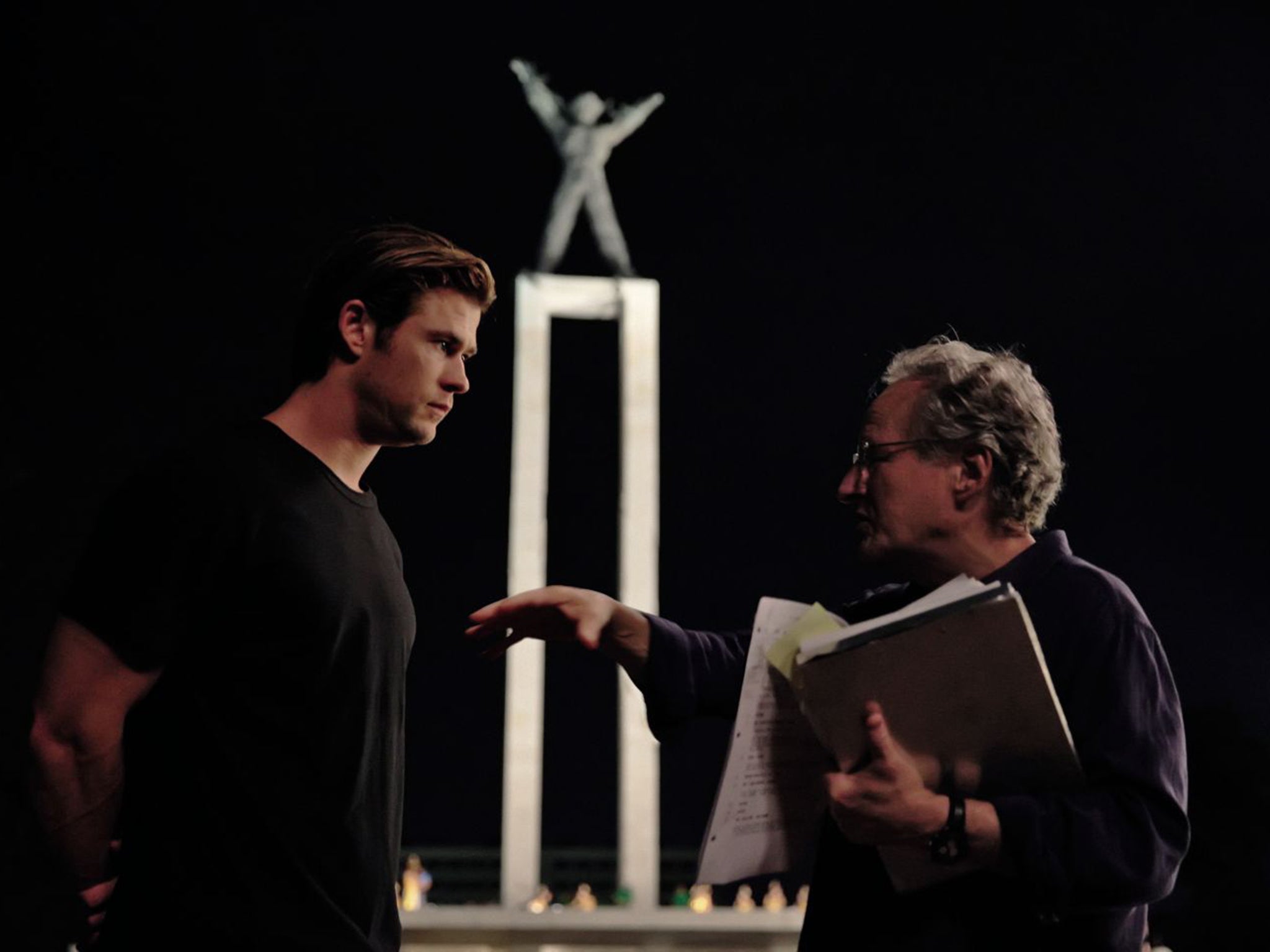

McKinlay tried, as a small cog in a large machine, to advise Mann during the making of Blackhat, which came out to mixed (at best) reviews in the US last month, and in Britain last Friday. The tech itself was the easy bit, and involved, among other things, teaching Chris Hemsworth to code. The Australian hunk of Thor and Rush fame plays a hacker who is sprung out of prison by the FBI to stop terrorists blowing up a nuclear power plant using malicious software that he had created years earlier.

The character, a sort of Ed Snowden with sunbeds and firearms training, is shown inputting code but, McKinlay says, "When I sat down with Chris he didn't know anything about computers or even how to type." He says Michael Mann had wanted to repeat the success of his first film, The Thief (1982), for which he recruited real thieves to teach James Caan, the leading man, how to crack a safe. "We spent a lot of time together but I was more focused on introducing him to the idea that not all hackers are skinny, pimply, loveless kids," McKinlay says. "This gave him confidence that he could be himself."

Typing lessons helped, too, and the hacking community has praised the coding scenes, the commands for which McKinlay wrote himself. His only technical complaint? "The sound effects," he says. "The ones that accompanied the scrolling of text across the screen were really distracting and annoying. So many films have that really high-pitched 'do I have tinnitus?' sound." But McKinlay, who's 36, was far more disappointed by the bigger picture. He says Michael Mann failed to relay or question what he sees as his government's over-reaching computing laws. "There's a history of Hollywood portraying things that the country doesn't understand bombastically," he says. "The ideology behind the film was wrong, and serves a Hollywood capitalist interest". There were other niggles, McKinlay says, including the portrayal of women (see Swordfish).

David Kirby, a former evolutionary geneticist who now explores the relationship between science and entertainment, says our expectations of film-makers have advanced even faster than technology, and compares the convincing coding scenes in Blackhat with Jurassic Park. "They had a lot of dinosaur experts for that but in one scene you see the girl waving her hands over a keyboard to make it look like she's hacking."

Tech-using cinemagoers are becoming harder to fool, one of the themes that Kirby, an American lecturer at the University of Manchester, explored in his 2011 book Lab Coats in Hollywood. Meanwhile, he adds, "The rise of special effects has put a premium on realism everywhere. If what surrounds the CGI isn't realistic, we still don't buy what's on the screen."

Another challenge ought to be the dating of technology during the time it takes to make a film, but Kirby says Hollywood has a tradition of not only keeping up with the times, but setting the pace. He cites Fritz Lang's 1929 silent classic, Woman in the Moon, as an early example. Lang recruited a team of scientists and gave them the freedom to imagine the rocket that the film's characters would use for their lunar mission. "They used it to present their ideas of what rockets should be," Kirby says. The scientists foresaw elements of space travel that would become real decades later, including multi-stage rockets and the countdown to lift-off.

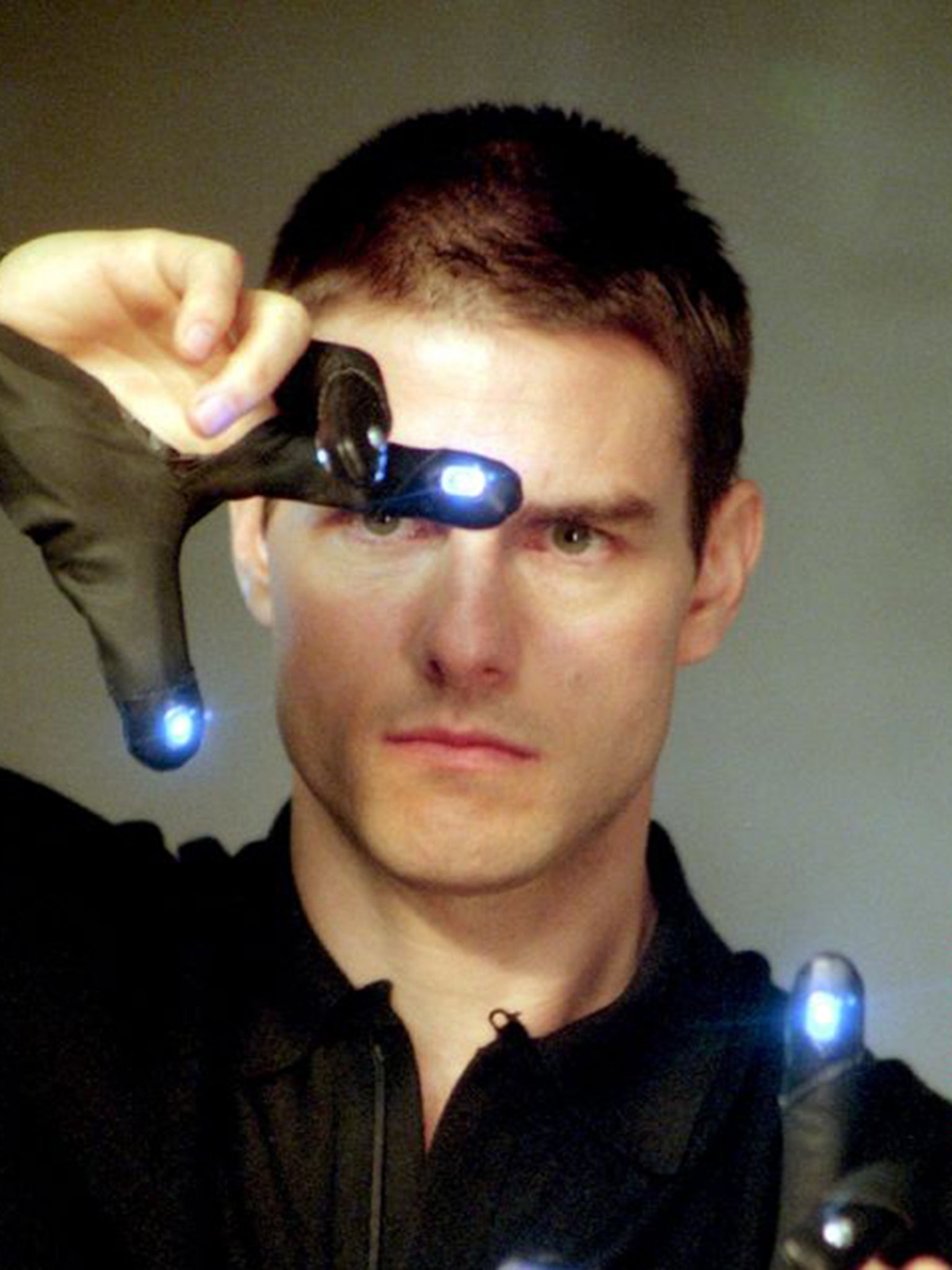

"I refer to this as pre-product placement," Kirby adds. "They don't exist yet but [film-makers] try to create desire for that technology to exist." It still happens, and Minority Report stands as perhaps the best modern example. Steven Spielberg employed an army of experts to create a blueprint for the film's 2054 setting, when technology allows Tom Cruise to predict crime. John Underkoffler, a computer interaction genius at MIT, was responsible for the multi-touch interface that Cruise's character works like a conductor. It was stunning to audiences in 2002, but also rooted in science fact.

"Unlike so many people who approach these technologies and say, we just need some waving hands, he said no, what if this were real and invented a whole system," Kirby says. "It looked so authentic and that's what got him the funding to make it for real." In 2010, eight years after the film's release, Underkoffler, who has also worked on the Iron Man films, demonstrated g-speak at a conference. It wasn't as polished as Cruise's computer but it was the same tech.

Audiences still require occasional clunky cues. Sticking with Minority Report, Kirby says production designers used mobile phones that were much bigger than the future demanded. "They told me that they could have designed something so small that it wouldn't have been visible but how would the audience know that characters were talking to each other? In that case they had to make the tech outmoded to be convincing."

A complex in film has worked to benefit other industries, too. After Fritz Lang's vision of space travel became real, Nasa established a dedicated Entertainment Industry Liaison in the 1960s that not only consulted for Hollywood but also cultivated links with it to promote its work. Collaborations have included Apollo 13, the very realistic true-life thriller, but also the use of Nasa logos in Mission to Mars and Space Cowboys.

Chris McKinlay will soon make it to the other side of the camera, when his own life gets the Hollywood treatment. He was a translator in New York before making thousands as part of the MIT card counting team who gamed Vegas casinos, themselves becoming the subject of films and books. He then made his own name as a hacker in 2012, when he manipulated the algorithms behind the OkCupid dating site to effectively become the most popular guy in America. He got engaged last year as a result, and has sold the film rights to his story. Will he be his own tech consultant?

"Ha, then I'd really lose my shit," he says. "But a friend told me that if you sign away the rights to your life, it's not your story any more. You have to let it go and watch."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments