Cyber culture: Why not all Twitter followers are true believers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are three ways to accumulate followers on Twitter.

One is to achieve sufficient real-life fame that we all want to read your brainfarts, regardless of their quantity or quality. The second is to knuckle down, for years if necessary, slowly accumulating connections one by one due to your wisdom, your searing wit, your sycophancy or all three. The third way is to give £100 to a company selling fake followers and obtain 25,000 of them overnight. Boom. Problem solved.

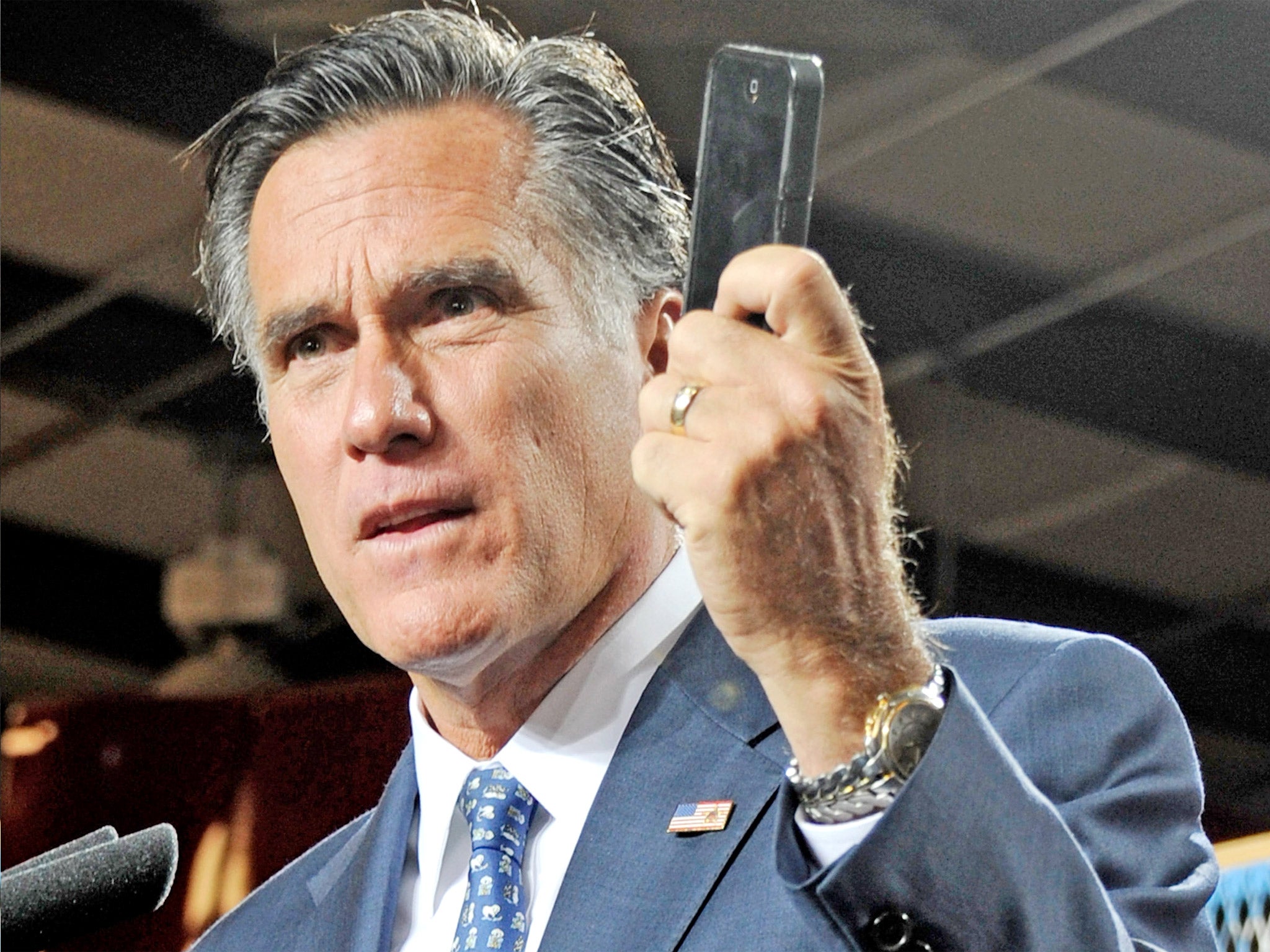

There's no question that having legions of followers on Twitter is worth something, however nebulous that something might be. Why else would companies devote the resources they do in order to "engage" us online? But having lots of fake followers would seem to be worth nothing at all. After all, they're not going to pay any attention; they're just a statistic. Last summer an eagle-eyed politics buff noticed that the number of Twitter accounts following US presidential hopeful Mitt Romney (pictured) surged unnaturally – by about 117,000 – on one particular day; it turned out that 80 per cent of these new followers had only joined Twitter in the preceding few weeks, and many hadn't even posted anything. They were almost certainly fake. As someone pointed out at the time, that's like filling a stadium with mannequins, giving a speech, then boasting about how you gave a speech to a packed stadium.

But large numbers of followers or Facebook "likes" do look superficially impressive. It gives people the impression that you're doing social media "right". As one company selling fake followers puts it: "Would you rather try a restaurant that looks busy, or one that's empty?" Followers breed followers, and likes breed likes.

But with a burgeoning black market in social- media enthusiasm now worth millions of dollars, why should we believe the numbers any more?

Twitter's policy of allowing us to have multiple accounts puts it at particular risk. Some companies control hundreds of thousands of Twitter accounts, and can have them spring into action with a click of a button. Analyst Gartner estimates that, by next year, between 10 and 15 per cent of social-media endorsements will be fake, with retweets, likes and follows all purchasable entities, creating a bizarre landscape of pseudo-enthusiasm where the distinction between real and fake is increasingly difficult to discern. And it'll happen whether we "like" it or not.

Forget the smartphone, 2013 is the year of the phablet

Back in 2003, Nokia launched the N-Gage (pictured). Part gaming console, part phone, it achieved notoriety because of the preposterous way you had to hold it to your head in order to make calls – as if you had "one very large ear", as Wikipedia puts it. The derision heaped upon it caused consumers to consider whether or not they'd look stupid when they called someone, and they made their choices accordingly. But over the last few months, phoneshave reached eyebrow-raising proportions. The other day a friend of mine fished a Sony Xperia Z out of her bag and I giggled at it in the same way as I giggle at the sight of a 1980s' brick phone.

And they're getting larger. Samsung in particular is sticking to the maxim that bigger is better, with the imminent Galaxy Mega coming in two sizes – one with a 5.8in screen, another measuring 6.3 inches. With many mini-tablets only a fingernail larger at 7in, the two are now butting up against each other, creating a class of device known as the "phablet". Indeed, Reuters proclaimed that 2013 would be the year of the phablet – and while we might snort with derision, ridicule the convergence and quietly assert the ergonomic "truth" that phones should be iPhone-sized and tablets should be iPad-sized, the figures say otherwise. Samsung's Galaxy Note, with its 5.3in screen, has sold millions; we've been seduced by big, glossy screens, regardless of how much they cane the battery. Many of us like huge phones in a way we would never have done a couple of years ago. You'd have thought that, by now, the tech industry would have worked out the optimum size for a smartphone – but, perhaps surprisingly, there is no answer to that question; it's as subjective an issue as the ideal length of a piece of string.

Will Facebook Home feel like a second skin?

Tomorrow sees the official launch of Facebook Home. Not quite a mobile operating system, not quite an app and not quite the Facebook Phone that some predicted. It's probably best described as a "skin" for the Android operating system, bringing everything Facebook-related to the front and centre of your phone, and shoving everything else out of the way. No longer will you need a Facebook app, because Facebook will be in your face pretty much constantly. Of course, those who despise everything Facebook stands for will give this product an exceptionally wide berth – but its launch raises interesting questions about the way our smartphones operate, and indeed the entire direction of the mobile ecosystem.

Facebook Home's very existence is down to the open source nature of Google's mobile operating system, Android; the code is available for any developer to use under a free software licence. As Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg gleefully pointed out, this meant that Facebook didn't need to work with Google. They just got on with it. From next week, you can use Facebook Home by either buying an HTC First (coming to the EE network in the UK later this year) or by downloading it from the Google Play store and installing it on your Android phone – although initially it'll only work with a select number of high-end sets, including the HTC One and Galaxy S3. Thereafter, your phone becomes a Facebook delivery machine, gently guiding messages, music, video, news and games through a Facebook portal.

It's easy to see how Facebook will benefit if Home catches on. It will effectively become the gatekeeper to your mobile existence, gathering data and using it to target advertising back at you. Also, at a stroke, Facebook's competitors (such as Google) will be demoted to a secondary screen – which, of course, requires effort to call up. And, as we know, we're pretty lazy creatures. By blinkering customers to the myriad capabilities of an Android handset, Facebook gains more control, while publicly self-congratulating over the way it's enabling humans to "connect". Apple, of course, would never allow such desecration to its precious operating system. But it's distinctly possible that kids in particular will be seduced by Facebook Home. And if other companies follow suit, using Android to create Twitter Home, Pinterest Home and who knows what else, who's to say that other Apple customers won't be seduced to Android too?

A very cunning fox with a dirty old secret

The web browser Firefox reached version 20 last week. One of the exciting new features trumpeted by its maker, Mozilla, was the introduction of "Private Browsing" to individual windows; anything you get up to in that window won't be recorded in your browsing or search history, while other windows operate as normal. Google Chrome and Internet Explorer already have this feature – but what tickles me is the way descriptions of the benefits of private browsing inevitably skirt around their primary purpose.

The feature has been known as "porn mode" ever since it was introduced in the Safari browser back in 2005 – but even if you spurn online pornography, Privacy Mode's main function is to keep your various nefarious activities secret from anyone who shares your computer.

Mozilla's announcement last week was a masterpiece of the genre: "You can shop for a birthday gift in a private window with your existing browsing session uninterrupted." Ah, yes. Birthday gift. That's what you were up to. Your secret's safe with me.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments