Boom or bust? Does supersonic flight have a role in the 21st century

A few years ago, Boeing took a serious look at the sonic cruiser, which can fly 150 miles an hour faster than current jets. Steven Cutts wonders if we’re about to see the return of a new ‘Concorde’

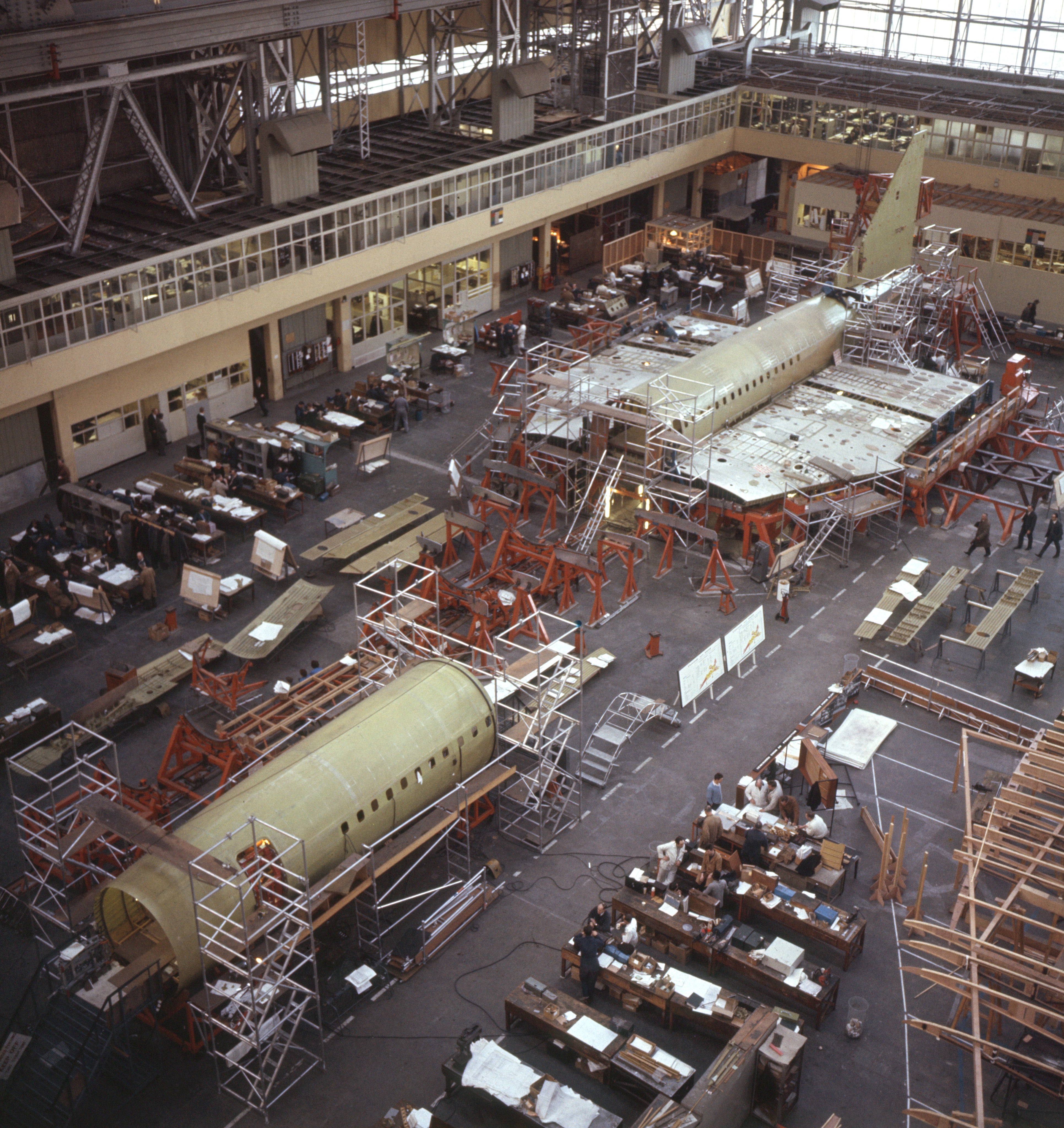

Modern aircraft are boring. None of them have increased their speed since the 1960s and – if anything – they are slowing down. After a 100 years of gradual increase in the speed of travel, the travel business plateaued out at around 500 miles per hour. It was not always so. For a brief moment in the 1970s, it looked as if the Anglo-French Concorde might be the future. With a speed of mach 2.04, Concorde could cross the Atlantic in three-and-a-half hours and became an airborne symbol of British and French engineering pre-eminence. But the last of the Concordes were retired in 2003 and, to date, no country or manufacturer has been able to match their speed.

By its very nature, aerospace research is high risk and high cost. In addition, it would be a mistake to pretend that other nations haven’t wasted huge sums on money or research projects that failed to provide them with a viable product. Having said that the British story is particulary sobering one, with successive disappointments of the Comet, TSR2 and then finally the Concorde. Ironically it was the modestly priced BAe 146 that won the coveted title of the best selling British airliner of all time. Every so often, you may turn on the news and notice a bunch of people protesting in London, asking for a higher standard of living, better funding for the NHS or a more generous pension. There are many things that determine our standard of living but waving a banner in central London isn’t one of them. Had each of our major aircraft projects been better managed, most if not all of our people would have a precipitously higher standard of living than they have now.

Concord had a good run and at the end of it, British Airways had logged more supersonic flying hours than all the air forces in all the world. But we didn’t export a single aircraft. How did the people who conceived the aircraft get it so wrong?

Prior to the Concorde project, almost all progress in aerospace was associated with greater speed and shorter journey times. There was no particular reason to suppose that the future would be any different from the past. Perhaps, forgivably, they failed to anticipate the advent of the environmental movement and the Arab oil shock, both of which dealt a killer blow to Concorde.

That isn’t to say that the project should be regarded as a total failure. Concorde did play a role in stimulating hi-tech research in the British and French aerospace industries and it’s probably no coincidence that right now that the British have 17 per cent of the global aerospace market by value. In an age when the centre of gravity was shifting to the US, Concorde dramatically shortened the journey time from New York and London and in doing so, it did a lot to draw influential Americans to Europe.

Men who might have shied away from an eight-hour stint in business class happily signed up for a $5,000 return trip on Concorde, secure in the knowledge that they’d only be airborne for just over three hours. But there were downsides too. Politicians and taxpayers alike became reluctant to risk such a huge proportion of their research and development budget on one high profile project.

Cruising at 500 miles an hour, most modern airlines spend about a third of their money on fuel. Even minor variations in the price of a barrel of oil can put a dent in their profits

Cruising at 500 miles an hour, most modern airlines spend about a third of their money on fuel. Even minor variations in the price of a barrel of oil can put a dent in their profits. Since the 1950s, the speed of jet aircraft has very slightly decreased but the efficiency of jet engines has increased by about 1 per cent every year.

Air travel was expensive, something that not everybody could afford. Now it’s widely available. Only by shifting immense numbers of people can the airlines stay in business. By implication, it’s difficult to operate an aircraft that only caters for a tiny minority.

In spite of all this, a supersonic renaissance may be just around the corner. Several companies are planning a supersonic transport and – we should add - looking for investors. The scale of the investment required is staggering and any potential backers should be warned that research budgets of this kind have a habit of spiralling out of control.

So what are the obstacles to success? Well, to start with there’s supersonic boom. The boom created by Concorde had the potential for shattering windows. Alarmed by the whole idea, the American government banned all supersonic flight over land, significantly downgrading the commercial opportunities of any such aircraft. Having said that, we should not forget that three quarters of the earth’s surface area is covered by water and there are plenty of routes that stay over water.

Nevertheless, the elimination of the supersonic boom would greatly benefit any future aircraft. In days gone by, this very suggestion would have seemed risible but in modern times, several research projects have concluded that this is not impossible. Marketing teams for the next generation of aircraft like to mention that their sonic boom would be no distracting than the slamming of a car door.

Not surprisingly, much of this work has occurred in the US and the American space agency, Nasa, has been working on this technology since the 1980s. Their X-59 prototype is now under construction by Lockheed Martin and should be ready this year.

Avoiding the sonic boom isn’t the only issue in play. One of the most distinctive design characteristics of the Concorde was the nose cone, which famously bent forwards during take-off and landing, just to give the pilot a better view. From an aerodynamic perspective, a supersonic jet works better with a tapered nose, but this is a major handicap to the crew, who can barely see the runway.

More recently American engineers have proposed to eliminate the windows from the next generation SSTs and provide the pilots with large scale television screens linked to a system of cameras. If this system fails, the crew would be completely blinded and one can’t help but feel apprehensive about this approach. There is, presumably, more than one camera, more than one screen and more than one power supply.

Most large jet engines improve their efficiency by about 1 per cent a year and if any of the major manufacturers stopped doing this, they’d go out of business very quickly. Concorde used a fantastic amount of fuel to travel at mach 2.2, most notably at take off when the extensive use of afterburners sprayed fuel into the rear of the engine in order to generate enough thrust to take off.

Boom, an American start up with ambitions to reactivate super sonic flight, believes that its own aircraft will be able to achieve supersonic travel without using afterburners. Boom appears confident it can provide a supersonic ticket for a price similar to that associated with a business class traveller on a 747. The aircraft would carry more than 50 people. As things stand, Boom has a budget of less than $200m, nowhere near the $3.5bn estimate for the aircraft it proposes to build. On a more positive note, it hopes to start cutting metal later this year and plans to fly a small-scale demonstrator in early 2021. Richard Branson and the Japanese national airline have both put in orders for this project and they seem to be making steady progress.

The Nevada-based Aerion Corporation intended to build a small business jet that could carry about a dozen passengers at a modestly impressive mach 1.4. Their “AS2” business jet had aimed to achieve a boomless cruise, whereby the supersonic shock wave would be diverted up into the sky rather than down onto the unsuspecting residents on the ground. They thought it could fly from New York to London in 4.5 hours. It was also suggested that it would run on synthetic fuel, thereby reducing the environmental impact. Aerion planned to bring the machine to market by 2026, but like a lot of hi-tech start-ups it struggled to raise investment and closed in May 2021. It’s important to remember that the budget for all of these projects are bolstered by bravado.

In fact, there are people who are willing to pay thousands of dollars to save a few hours in the sky and the absolute number of high-net-wealth individuals is still on the rise. But how big is this market? Basically it was big enough to sustain three of four Concordes in the BA fleet and a similar number for Air France. From the perspective of the manufacturer, there is a certain number of aircraft that you have to sell just to recoup your research and development costs and in the case of Concorde that number was 70. (They sold none.)

Remember that there are other approaches to reduced journey times. In more recent years incremental improvements in materials and fuel efficiency have made it possible to fly from London to Perth without refuelling. While the actual speed of the aircraft is little different from their predecessors, such aircraft have dramatically reduced overall journey times by avoiding the repeated delays associated with landing, refuelling and take off.

A few years ago, Boeing took a serious look at the so-called sonic cruiser, which would fly about a 150 miles an hour faster than current jets, just short of the speed of sound. Such an aircraft would reduce journey times on trans-Atlantic flights without having to wrestle with the political issue of the sonic boom. Remember that when Concorde flew out of Heathrow, it couldn’t play the mach 2 card until it was well past the West Coast of Ireland and this further reduced the time saving advantage that it had been built to achieve. Boeing’s sonic cruiser could have initiated its marginally higher speed while it was still over the British Isles. In the event, the airline industry wasn’t as enthusiastic about the sonic cruiser as Boeing had expected and we were back to conventional speeds all over again.

Was Concorde a failure? In pure economic terms, yes it was. British economic prosperity is critically dependent on exports and Concord failed to achieve a single export order

If we had thousands of supersonic aircraft, all of them flying at superlative altitudes, the issue of pollution would become impossible to ignore. Part of the reason that this wasn’t highlighted in the Concorde era was that there were so few machines flying. Of course, there are ways around this. Latter-day supersonic innovators talk about carbon offsets and the miraculous benefits of synthetic fuel. Such measures are more than feasible, but it’s by no means certain that they will be deemed effective by future legislators and there is a significant risk that the next generation of supersonic transports could be banned before they get airborne. It’s just another headache for the people trying to raise the billions of dollars in research and development funds that this kind of project requires.

Was Concorde a failure? In pure economic terms, yes it was. British economic prosperity is critically dependent on exports and Concord failed to achieve a single export order. But in other ways it was a triumph. Like the Falkland’s war, it wasn’t worth the money but it managed to press buttons in the nation’s soul that most mainstream commentators failed to register. It seemed to send out a message to the outside world. That we were still exceptional and we were still a force to be reckoned with on the global stage.

The people that dreamt up Concorde failed to anticipate the precipitous increase in the price of oil that followed the Arab-Israeli war of the early 1970s. On a similar note, we can probably forgive them for their failure to foresee modern day environmentalism.

A few years late came a critical moment in the 1970s, when the then Labour government had to decide whether to cancel the Concorde project or the Channel Tunnel. Under pressure from Tony Benn (whose constituency was assembling the actual aircraft), it elected to cancel the Channel Tunnel, with the drilling teams just a few hundred yards out to sea. Concorde failed to achieve a single export order and it took the Thatcher government of the 1980s to build the tunnel we know today. If you want to live in a first-world country with all the benefits of a first-world life style, you can’t make mistakes on this scale.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments