China is building a train that’s faster than a plane – but will it work?

More than a decade after Elon Musk’s Hyperloop pipe dream, China’s biggest missile manufacturer may be finally about to realise it, writes Anthony Cuthbertson

In 2013, Elon Musk published a 58-page proposal for a brand new form of transport. Having popularised electric cars as the boss of Tesla, and ushered in a new era of private space travel as the owner of SpaceX, the billionaire believed there was a better way to deliver mass transit than trains, planes and buses.

He called his solution Hyperloop Alpha, and he claimed it was safer, faster, cheaper, cleaner, and even more resistant to earthquakes than the current alternatives. “Short of figuring out real teleportation, which would of course be awesome (someone please do this), the only option for super fast travel is to build a tube over or under the ground that contains a special environment,” he wrote in the white paper, which can still be found on Tesla’s website.

Despite detailing a proposed route between Los Angeles and San Francisco, Musk never intended to actually build or fund it himself. Instead, he made the design concept open source, encouraging others to advance its development and bring it to reality. More than a decade later, and halfway around the planet from where it was originally intended, Musk’s pipe dream may finally be about to be realised.

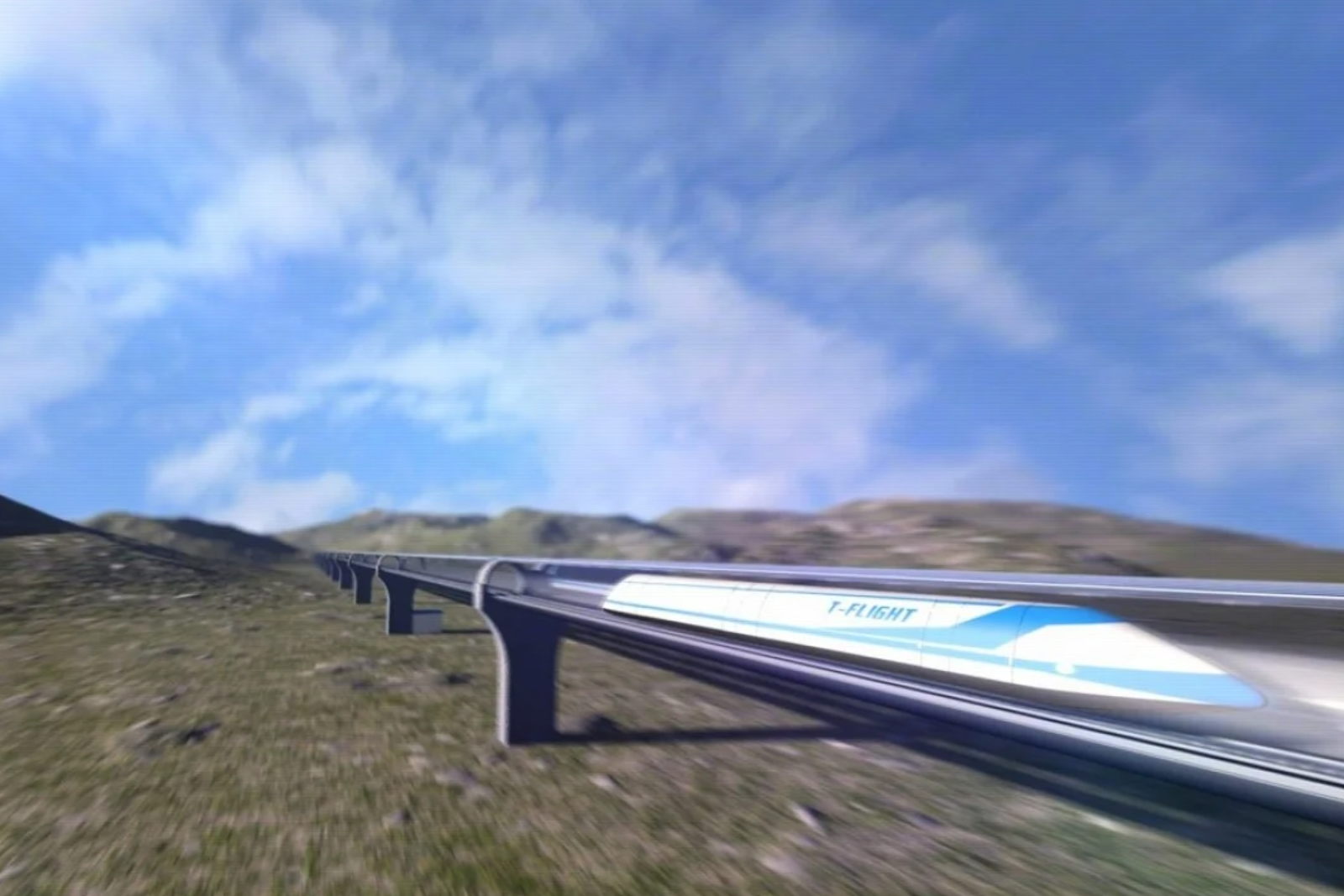

China’s biggest missile manufacturer has shot into contention as the top candidate for delivering the world’s first hyperloop system, recently unveiling a vacuum-tube maglev train capable of travelling 623 kilometres per hour (387mph). This is roughly twice the speed of a Japanese bullet train, though the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) claims its T-Flight vehicle has the potential to reach speeds of more than 1,000 kph – faster than the average cruising speed of commercial planes.

It is not the first attempt to build a hyperloop system. The initial excitement surrounding Musk’s proposal saw several well-funded startups make an attempt at it, though each came up against various technological and regulatory constraints.

One of the most high-profile casualties was Hyperloop One, which raised more than $450 million in its quest to create the futuristic transportation system. After securing partnerships with the likes of Deutsche Bahn and General Electric, the venture saw early success with the unveiling of a test track near Las Vegas in 2016.

The following year, entrepreneur and airline founder Richard Branson joined the board of directors and injected enough investment to rebrand the project Virgin Hyperloop. An initial focus on passenger transport pivoted to freight, before the endeavour fell apart. In December 2023, Bloomberg reported that the company had declared bankruptcy and was shutting down.

Other efforts include Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HyperloopTT) and Hardt Hyperloop, which are both planning to build test tracks in Europe this year. One of the biggest remaining roadblocks towards commercialising the technology is a lack of understanding from lawmakers about how such a nascent and unproven transport system fits in with the existing infrastructure. There is also a fear that such a bold undertaking could end up like the famous Monorail episode from The Simpsons.

“There is a lot of risk aversion,” Richard Geddes, a professor of policy at Cornell University and co-founder of the Hyperloop Advanced Research Partnership (HARP) told news site Smart Cities Dive in 2020, the year that Virgin Hyperloop successfully tested a passenger pod on the Nevada test track.

“Nobody really wants to sign off and say yes, this technology is safe for human travel, and then have some horrible accident occur. There’s a lot of risk aversion in the regulatory process anyway, but if you’re adding this element of it being a completely new technology that hasn’t been tested, then it’s going to be even slower.”

This is one reason why countries with authoritarian regimes or single layers of government can offer a way to implement such projects at scale without too much resistance. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are both pursuing hyperloop proposals, with Professor Geddes telling The Independent that their “vast wealth, relatively flat landscape and nature of the government” offer a path to push through big projects.

China’s CASIC has both the state backing and the funding to realise such ambitions in a relatively short timescale. More importantly, there is also the demand, with an increasingly urbanised population approaching 1.5 billion, spread across cities that take up to 56 hours to drive between. One route proposed by CASIC is between Beijing and Wuhan, a 1,200 kilometre journey that currently takes four hours on a high-speed train. The company claims the T-Flight could achieve it in 30 minutes, though gives no word on cost.

The only remaining obstacle, it seems, is the technology itself. The current speeds of CASIC’s T-Flight prototype are already record breaking for a maglev train, though it has only been achieved on a test track with no passengers on board. “Science and technology progress step by step and some aspects of this project are still in unchartered territory in China,” Mao Kai, CASIC’s chief designer on the T-Flight project, told the South China Morning Post following the latest test run. “Every step is challenging, and it’s a complex system.”

As the hype surrounding hyperloop has diminished, so too has the hope that such an ambitious transport system will ever be built. The word hyperloop has become a by-word in tech circles for overly ambitious projects that have no chance of ever materialising. Yet despite the misgivings, the promise of cheap and efficient transport means that efforts still persist.

“Hyperloop has a number of incredible benefits as a new mode of transport, including energy usage, speed and safety,” said Professor Geddes. “There’s too many smart people working on it and too much capital behind it for it to not be realised.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments