Child becomes first patient to be cured of potentially fatal illness using 3D-printed biodegradable implant

The boy was one of three babies in the US who underwent surgery involving the insertion of 3D printed splints into their throats

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A three-year-old boy has become the first patient in the world to be cured of a potentially fatal illness with a biodegradable implant made to the patient’s exact specifications by 3D printing technology, doctors have said.

The boy was one of three babies in the United States who underwent pioneering emergency surgery involving the insertion of 3D printed splints into their throats. These were designed to keep their windpipes open while allowing the infants to grow normally.

The first operation was on Kaiba Gionfriddo from Ohio in 2012 when he was just three months old and suffering from tracheobronchomalacia, which affects about 1 in 2,000 babies and causes the windpipe to collapse periodically, preventing normal breathing and leading to profound health complications and premature death.

Scientists announced that all three boys have responded well to the treatment, with Kaiba now deemed to be effectively cured. His biodegradable implant has been partially re-absorbed by his body meaning that he no longer has to rely on it completely for breathing.

“We report that this engineering design has worked as intended and that the first [patient] to receive this implant three years ago appears to be cured of tracheobronchomalacia with the splint hat has not functionally degraded,” said Glen Green, who was part of the operation team at the C S Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

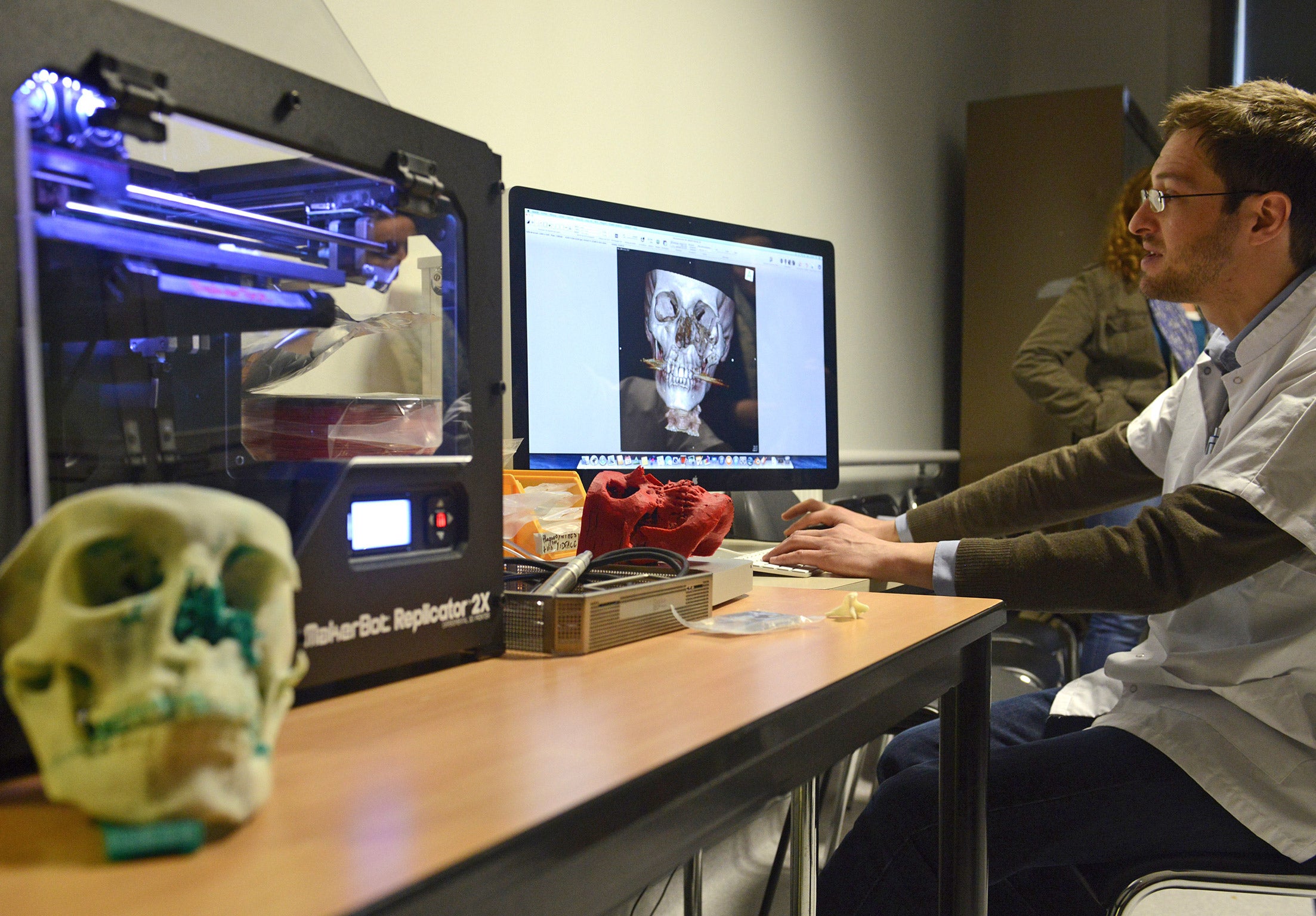

The implants were made from a non-toxic, degradable polymer printed layer by layer into its final three-dimensional shape based on information gathered directly from CT scans of each baby’s windpipe. The scientists fine-tuned the printing instructions for each device to suit the individual needs of each baby boy.

“These cases broke new ground for us because we were able to use 3D printing to design a device that successfully restored patients’ breathing through a procedure that had never been done before,” Dr Green said.

“Before this procedure, babies with severe tracheobronchomalacia had little chance of surviving. Today, our first patient Kaiba is an active, healthy 3-year-old in preschool with a bright future. The device worked better than we could have ever imagined,” he said.

April Gionfriddo, Kaiba’s mother, said: “The first time he was hospitalised, doctors told us he many not make it out. It was scary knowing he was the first child to ever have this procedure, but it was or only choice and it saved his life.”

The two other baby boys received their implants at the ages of 5 months and 16 months and, like Kaiba, they are now free of the normal restrictions patients have to live with, such as being treated with powerful drugs and placed on mechanical ventilators, according to the study in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“The airway splint is one of the earliest 3D printed medical implants. More importantly, this is the first 3D printed implant specifically designed to change shape over time to allow for a child’s growth before finally resorbing as the disease is cured,” Dr Green said.

Scott Hollister, professor of biomedical engineering at Michigan University, said that each implant was designed to accommodate the growth of each baby in what the scientists have called “4D” design.

“We were concerned not just with how the splint opens the airway when implanted, but also that the splint allows the airway to grow over time,” Professor Hollister said.

“Allowing growth is part of 4D material design, with the fourth dimensional design being how the splint opens during airway growth because of is geometry, and resorbs as time progresses to leave a normal airway,” he said.

The three boys were treated as emergencies because there was no other viable option. However, a clinical trial involving about 30 patients with 3D printed throat splints is now being planned, the scientists said.

The team also printed out polymer replicas of each boy’s windpipe and lungs so that they could practice on inserting the implant before the actual operation. The researchers said that it can take between one and two days between scanning a patient and producing an implantable device.

Dr Green said: “We are pleased to find that all of our cases so far have proven to improve these patients’ lives. The potential of 3D-printed medical devises to improve outcomes for patients is clear, but we need more data to implement this procedure in medical practice.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments