The tech revolution in cars has stalled. Why?

Apple and Tesla have hit serious bumps in the road in their promise to change the way we drive, writes Andrew Griffin. So how long will we have to wait for the car of the future?

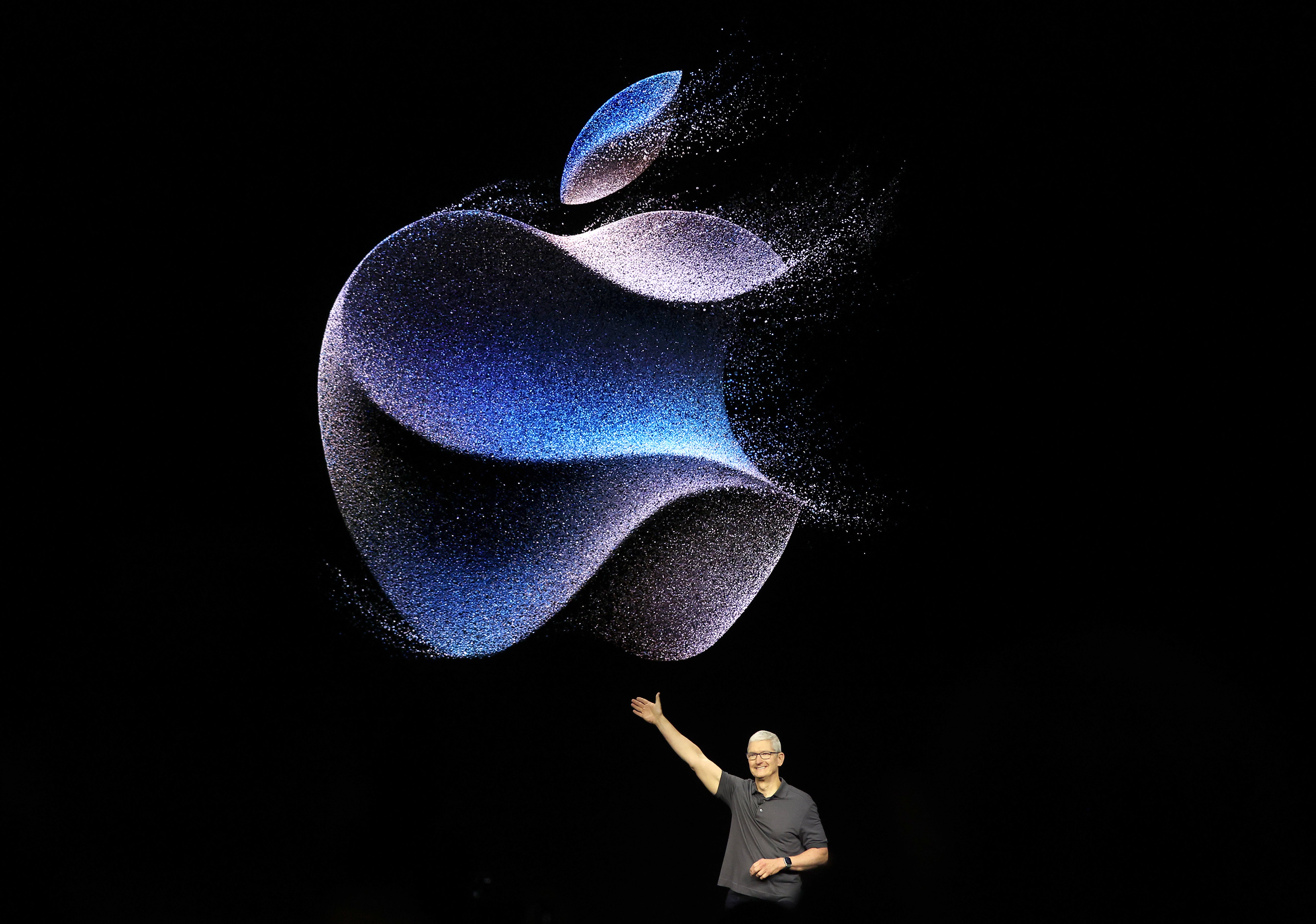

Roughly 10 years ago, Apple believed it could build the best car ever made; better even than the futuristic-at-the-time Tesla Model S. In recent weeks, that dream was seemingly over following reports that indicated Apple was shutting down its car project. Tesla’s future was in question, too, as sales and its share price slid.

Apple wanted to build a car that could drive itself. Owners could instead focus on the wide-ranging infotainment systems that would presumably be built in. Apple has already been working on those: its CarPlay system, like competitor Android Auto, is now integrated into most new cars and has led to a revolution in car infotainment.

Apple’s car was supposed to be a competitor to Tesla – but Apple might be happy not to be competing in that market. In the last three months, Tesla shares have plunged more than a third, and the company announced this week that it has sold far fewer cars than it had hoped to.

At the same time, Tesla has been looking to bring back some of the excitement with new models, including the Cybertruck, introduced as a concept in 2019 and starting to arrive with customers in recent months. As those first drivers have received them, excitement has flourished but so has controversy – early recipients have complained about the technology inside of the car, and critics say the sharp edges and large design of the truck’s outside mean that it is unsafe for other road users.

But it isn’t only the obviously futuristic vehicles that have left consumers frustrated with the incursion of technology into their cars. Last year, a major survey showed that drivers were unhappy with their vehicles, pointing to changes to the infotainment system as their main complaint.

JD Power’s Automotive Performance, Execution and Layout (APEAL) Study has been running for 28 years – but last year was the first time that overall satisfaction declined for two years in a row.

The problem seemed not to be so much the cars themselves but the technology found inside their dashboards. In 2020, 70 per cent of drivers preferred to use their built-in system for listening to music, for instance; last year, that had fallen to just 56 per cent. Instead, they are turning to systems that allow them to mirror their phone, in the form of CarPlay and Android Auto.

Those technology companies are pushing further and further into car dashboards: the next-generation version of Apple’s CarPlay is set to start arriving this year, and will be able to take over the whole dashboard, though car makers will be able to give it their own look and feel.

But some companies have rejected that onward march of tech companies into their cars and looked to ditch CarPlay, apparently looking to ensure they keep control of their own dashboards rather than hand it over to Apple and Google. That hasn’t always gone well.

Last year, General Motors said that it was ditching CarPlay in its 2024 models. It gave a variety of reasons: ensuring control of the whole car would make for better features, it said, but it also noted that it could get new subscription revenue from those tools. The change was controversial: it was met with a host of criticism, and early reviews of the first cars to make the change complained that the new infotainment system came with problems.

Changes to the inside of the car have proven controversial for years. Perhaps the most obvious was when Tesla swapped its round steering wheel for a flatter “yoke” – it made the cars look more futuristic, but also led to users complaining about U-turns and other manoeuvres. It was supposed to be a new change to the default design of the car, but customer complaints meant that Tesla had to make it optional, and then it started allowing customers to pay to have the yoke changed back to a round one.

It isn’t only the wheels that have seen the march of progress, with the sticks and stalks that are arrayed around them also affected by technology changes. In recent years, carmakers have moved away from physical controls and towards touchscreens; air conditioning and other features have gone from sticks to swipes.

Last month, European regulators said they were launching a plan to try and encourage car companies to bring those physical controls back. “Almost every” carmaker has moved controls onto touchscreens, “obliging drivers to take their eyes off the road and raising the risk of distraction crashes”, NCAP’s Matthew Avery told The Times.

NCAP will not require vehicle makers to use physical switches. But it will instead introduce new rules from 2026 that mean a car can only achieve the highest safety rating if it has physical controls for turn signals, the horn, the windshield wiper and other features.

The move away from switches and onto touchscreens is no doubt partly a cost-saving measure: one touchscreen can control multiple functions, while the introduction of physical switches and buttons can quickly add up at scale. But car companies might also feel they are moving towards a time where cars are less like machines and more like computers, the kind of revolution that has been happening since electric vehicles became mainstream and infotainment turned smart.

But that revolution too appears to be stalling. Part of Apple’s decision to ditch its car project appears to have resulted from the fact that building a fully self-driving vehicle is incredibly difficult; Tesla’s woes stem partly from a broader slowdown in the electric vehicle market, as consumers worry about charging infrastructure and other problems.

The car of the future is not arriving quite as quickly as manufacturers might have hoped. But customers might be very happy for them to apply the brakes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments