'Brain training' game helps people with schizophrenia live a normal life

The computer game was based on scientific principles that are known to 'train' the brain in episodic memory

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A computer game designed by neuroscientists has helped patients with schizophrenia to recover their ability to carry out everyday tasks that rely on having good memory, a study has found.

Patients who played the game regularly for a month were four times better than non-players at remembering the kind of things that are critical for normal, day-to-day life, researchers said.

The computer game was based on scientific principles that are known to “train” the brain in episodic memory, which helps people to remember events such as where they parked a car or placed a set of keys, said Professor Barbara Sahakian of Cambridge University, the lead author of the study.

People recovering from schizophrenia suffer serious lapses in episodic memory which prevent them from returning to work or studying at university, so anything that can improve the ability of the brain to remember everyday events will help them to lead a normal life, Professor Sahakian said.

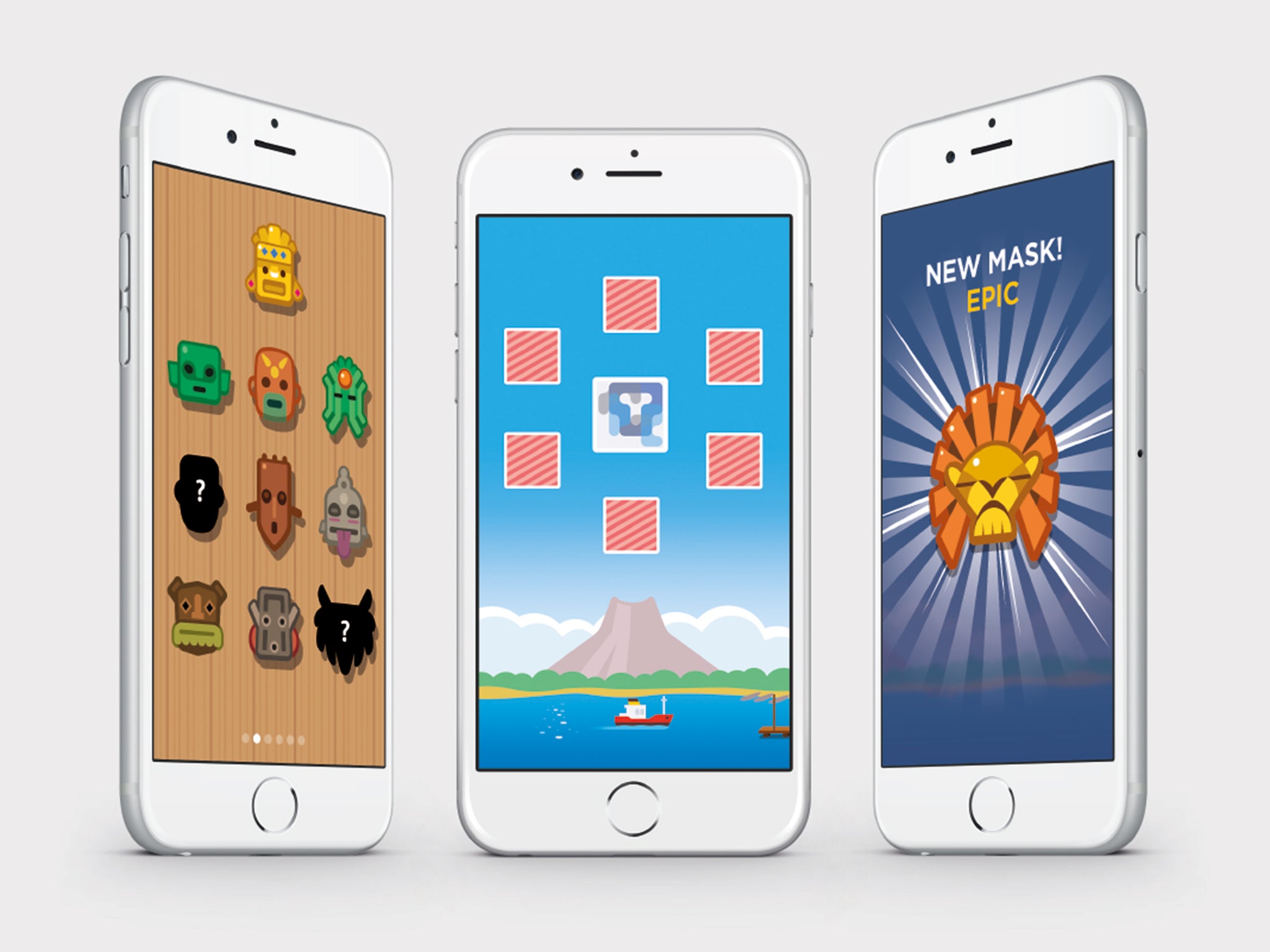

“This kind of memory is essential for everyday learning and everything we do really both at home and at work. We have formulated an iPad game that could drive the neural circuitry behind episodic memory by stimulating the ability to remember where things were on the screen,” Professor Sahakian said.

Schizophrenia affects about one in every hundred people and results in hallucinations and delusions – it is estimated to cost the NHS about £2bn a year in treatment alone, with wider costs for society such as lost work.

Although the main symptoms can be treated with anti-psychotic drugs, there is no proven drug therapy for treating losses in episodic memory, which has led scientists to find ways of training the brain through computer-based games.

“We need a way of treating the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as problems with episodic memory, but slow progress is being made towards developing a drug treatment,” Professor Sahakian said.

“So this proof-of-concept study is important because it demonstrates that the memory game can help where drugs have so far failed. Because the game is interesting, even those patients with a general lack of motivation are spurred on to continue the training,” she said.

Game designers worked alongside the Cambridge researchers for nine months to develop a gaming app called Wizard, which plays on the idea of having to remember different locations of characters on the screen of an iPad. Patients were involved in the game design to ensure they would understand it and enjoy it, Professor Sahakian said.

The study, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, involved 22 schizophrenia patients who played the game for eight hours over a period of four weeks, with players of the game being compared with non-players in terms of a psychological test known as global assessment functioning (GAF).

“The GAF measures participants' social occupational and psychological function. Importantly, the patients with schizophrenia enjoyed playing the game and were motivated to continue. The group that played the game was approximately four times better in terms of their memory than the group that did not,” Professor Sahakian said.

Professor Peter Jones of Cambridge University, the leader the study, said: “These are promising results and suggest that there may be the potential to use game apps to not only improve a patient’s episodic memory, but also their functioning in activities of daily living.

“We will need to carry out further studies with larger sample sizes to confirm the current findings, but we hope that, used in conjunction with medication and current psychological therapies, this could help people with schizophrenia minimise the impact of their illness on everyday life.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments