Scientists create tiny devices that work like the human brain

'Compared to a conventional computer, this device has a learning capability that is not software-based'

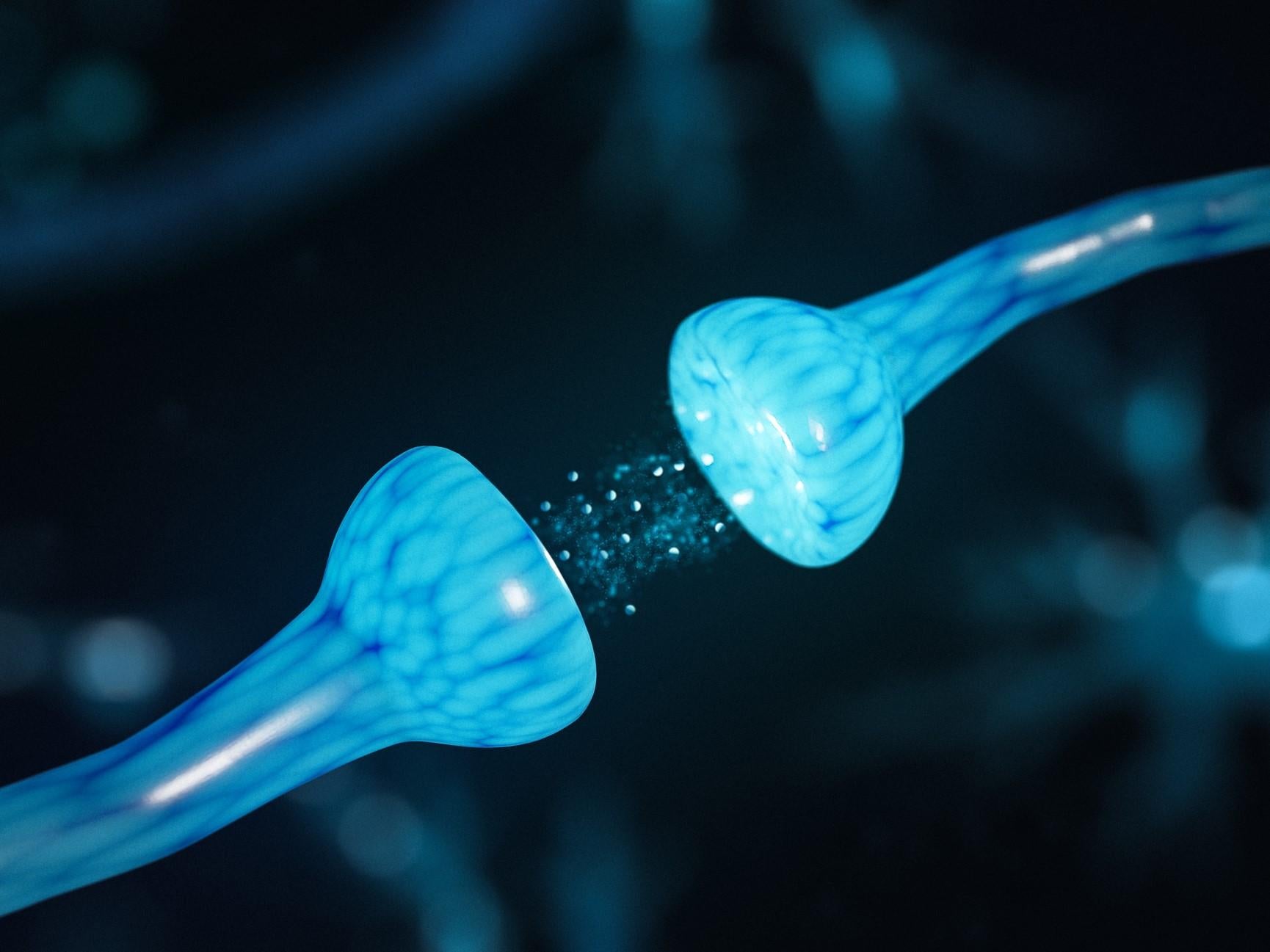

A major computing breakthrough has allowed researchers to develop ultra-low power devices capable of operating at the same voltage level as a brain.

Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst figured out a way to use biological, electricity conducting filaments to make an electronic memory device known as a memristor.

Using protein nanowires developed from the bacterium Geobacter, the scientists realised they could create a device as power-efficient as a human brain synapse. Details of the new technology were published in the journal Nature Communications.

"People probably didn't even dare to hope that we could create a device that is as power-efficient as the biological counterparts in a brain, but now we have realistic evidence of ultra-low power computing capabilities," said computer engineering researcher and co-author Jun Yao.

"It's a concept breakthrough and we think it's going to cause a lot of exploration in electronics that work in the biological voltage regime."

To test the nanowires, the scientists experimented with a pulsing on-off pattern sent through a tiny metal thread 100-times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

The pattern of positive-negative charge created an effect similar to the process of learning in a real brain.

"You can modulate the conductivity, or the plasticity of the nanowire-memristor synapse so it can emulate biological components for brain-inspired computing," Dr Yao said.

"Compared to a conventional computer, this device has a learning capability that is not software-based."

The biological nanowires offer many advantages over artificial silicon nanowires beyond simply requiring vastly lower amounts of energy.

The are more stable in water or bodily fluids, meaning they could be used for biomedical applications like heart rate monitor devices.

Dr Yu said they could even conceivably be integrated with existing biological processes for cyborg-esque functionality.

He said his team now plans to "fully explore the chemistry, biology and electronics" of the nanowires, adding, "This offers hope in the feasibility that one day this device can talk to actual neurons in biological systems".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks