How we uncovered Europe’s oldest bone tools

Matt Pope explains how a team from UCL discovered the oldest bone tools in Europe and reveals what they can teach us about their makers

Boxgrove in Sussex is an old stone age site, and it is where the oldest human remains in Britain have been discovered – fossils of Homo heidelbergensis. Part of an exceptionally preserved 26km-wide ancient landscape of stone, it provides a virtually untouched record of early humans almost half a million years ago.

The most perfectly preserved area of the site is known as the “Horse Butchery Site”, a spot where a large horse was slaughtered and processed some 480,000 years ago. Since 1994, we’ve worked on bone and stone artefacts from here – some of which are the earliest in Europe – as part of a multidisciplinary team led by the UCL Institute of Archaeology. This has given us important insights into the lives of the mysterious H heidelbergensis, which we have just released in a book.

My own research focused on the stone artefacts – more than 1,750 pieces of knapped flint. The tools, along with bones from a single large female horse, were discovered more than a quarter of a century ago, and the location of each artefact was plotted to the nearest millimetre.

This level of recording was achieved without laser survey equipment and digital photography – the two mainstays of modern archaeological site recording today. Instead, the excavation team used overhead photography, a darkroom set up in the local pub and pen and ink to meticulously record the position of each stone tool and fragment of bone.

Before being able to interpret what the early humans were doing at the site, we had to understand the deposits preserving the remains. These investigations revealed that the sediments themselves appeared to be inter-tidal marshland, which formed on the edge of a lagoon during a warm climate stage. As the early humans were butchering the horse, a high tide came in, preserving the site just as it was when the hominins moved away.

Preservation like this is very rare in any archaeological period, even recent ones. The fine silts buried the site over one or more high tides without moving the artefacts or bones any appreciable distance. This meant we could reconstruct early human behaviour at a revealingly high degree of resolution.

My job was to piece back together the stone artefacts from the site – a process is called “refitting”. Each stone flake removed by an ancient human will only fit, uniquely, to other flakes removed from the same block of flint immediately before and after it.

Refitting can give you a blow-by-blow picture of how an individual made a tool, readjusting and problem-solving, sometimes shifting position as they spent perhaps 10 or 15 minutes making each tool.

We don’t know where they slept, how they looked after their dead or what they ate alongside horses

From the refitting, we were able to document the manufacture of eight large cutting tools (known as handaxes or bifaces), the modification of other pre-existing tools and preparation of flint blocks brought to the site.

When combined with refitting of the bone, our detailed study revealed a remarkably intimate insight into a day in the life of these elusive people. While all the activity centred around tool making and horse butchery, we could track detailed movement during the day.

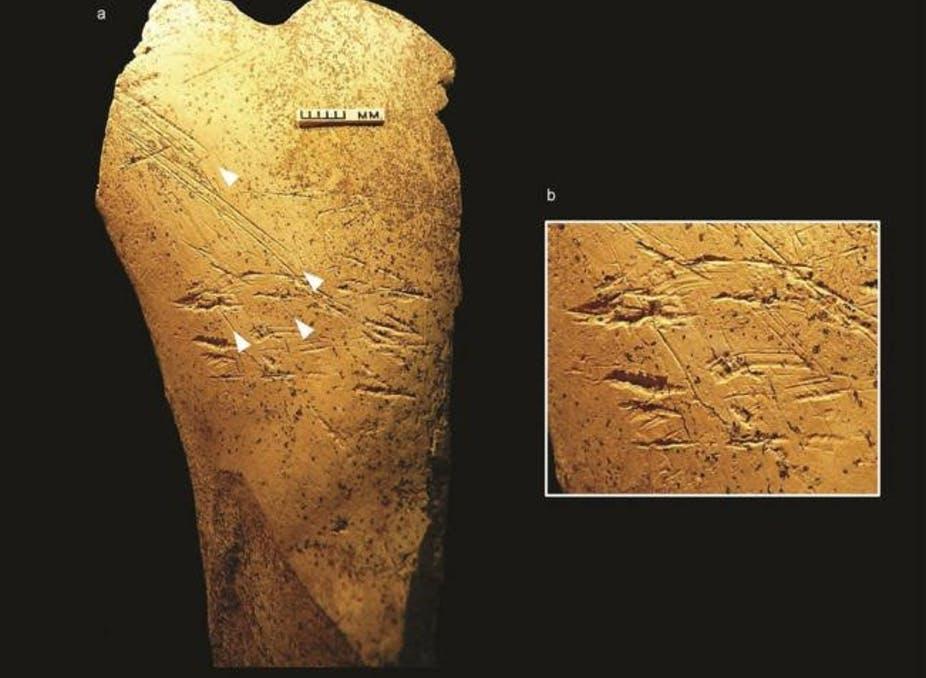

We saw that flakes were moved from piles of waste material on the edge of the site to be used in removing meat from the animal. Parts of the horse were also used as bone tools (see lead image) to make new tools, as revealed by incidental impressions of horse knees and legs left as shadows in the waste flakes. This suggests that the people understood the properties of organic materials.

The movement of flakes, the manufacture of large cutting tools and the bringing of older, weathered artefacts and blocks or raw material to the site suggested that a relatively large number of people were involved in the butchery. Given the extensive processing of the horse carcass, we believe it may have included an extended family of maybe 30 or more individuals.

This is incredibly valuable information because we know so little about other aspects of the Boxgrove people’s lives. For example, we don’t know where they slept, how they looked after their dead or what they ate alongside horses. The archaeological record is mainly focused on where their activities accumulated durable materials, such as stone and bones, which heavily frames our view of early humans.

As a result, our narratives sometimes focus on compartmentalised areas of early human life, such as ecology or technology. But a locale like the Boxgrove Horse Butchery Site reminds us, when looked at in detail, that all aspects of human adaptation are mediated through our most powerful evolutionary adaptations: social life and culture.

The Boxgrove people, like all other human species, were capable of sharing time, care and knowledge in all parts of their life. These connections, even in the most routine of daily tasks, have always contributed to our success and resilience.

Matt Pope is a principal research associate at UCL. This article was first published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks