'What could it be?': You've heard of black holes, but what about blue holes?

Scientists will venture into one of the deepest blue holes ever discovered this month, but what exactly are these mysterious holes in the ocean floor? Heather Murphy reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

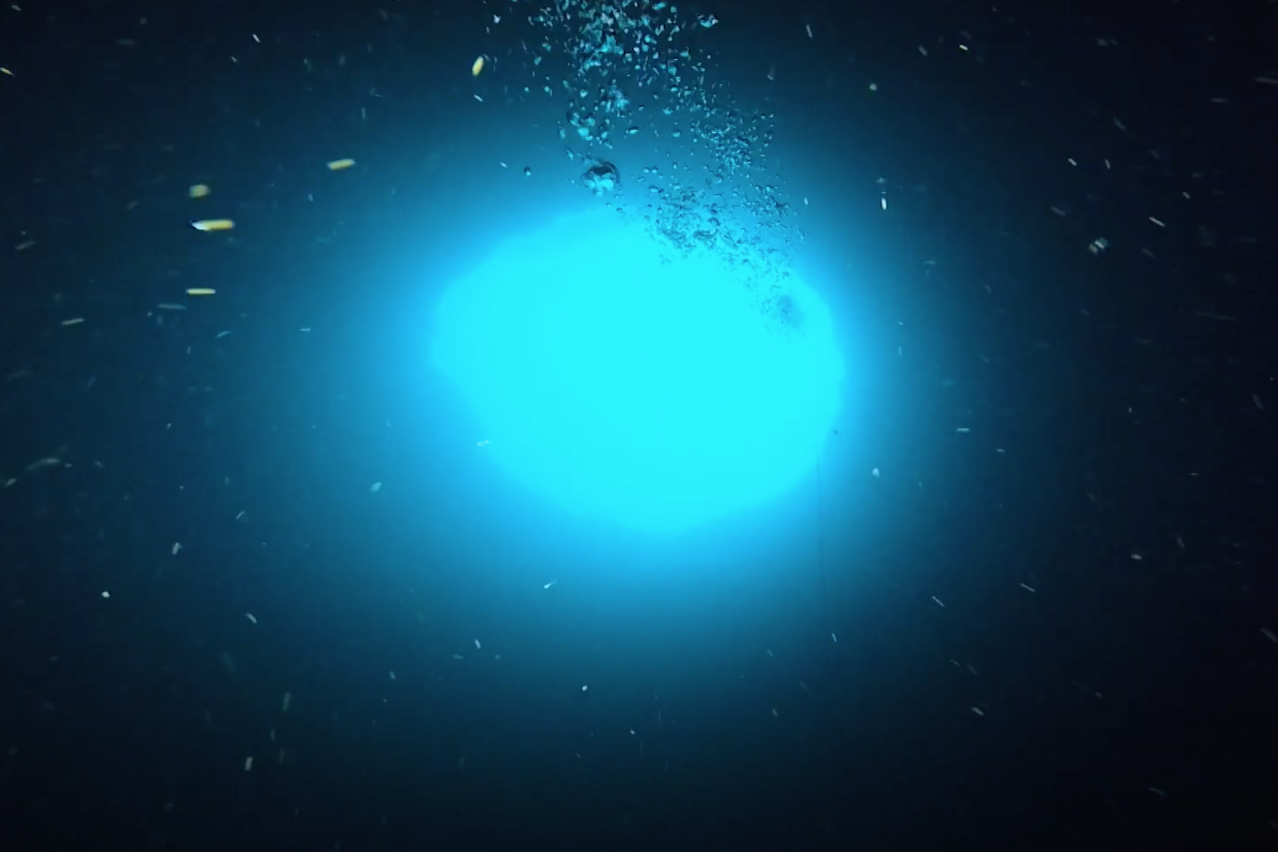

Your support makes all the difference.Sprinkled across the ocean floor, invisible from the surface, are hundreds — or maybe thousands — of sinkholes. These “blue holes”, as scientists call them, do not swallow up everything incapable of fighting their gravitational force, like their black hole cousins. But to those who study them, they are nearly as intriguing.

Last week, one particular blue hole off Florida’s coast — the Green Banana — captured the imagination of many a land dweller. Headline after headline has offered a variation on the theme: Scientists are flocking to a mysterious blue hole. One publication asked: “What could it be?”

What it is is the Green Banana, one of the deepest blue holes ever discovered, according to Jim Culter, a senior scientist at Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, and it’s on the verge of being studied in the most comprehensive way yet.

Scientists will venture into the Green Banana’s depths this month, when they hope to answer longstanding questions about whether the sinkhole — which extends around 275 feet, like an hourglass-shaped 20-storey building anchored in the ocean floor — connects to other sinkholes and whether fresh water flows within.

The scientists leading the mission to the sinkhole, which begins 155 feet below the ocean’s surface around 50 miles off St Petersburg, agree that the name, the Green Banana, sounds like a bar in Key West. According to Larry Borden, a longtime commercial fisherman and boat captain who has known about the Green Banana for decades, the name emerged in the mid-1970s after a boat captain saw a green banana skin floating by a known “spring”, as fishermen referred to the underwater sinkholes back then.

They were called springs, Borden says he had heard, because in the 1530s, when Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto was hanging out in the area, fresh water streamed out of the holes.

Spear fishermen who gathered near the holes centuries later, including Borden, wondered how deep they were.

Eventually, Borden told a diver friend, Curt Bowen, about the Green Banana, and in 1993, Bowen became one of the first people to dive to the bottom and map the blue hole. An article in Advanced Diver Magazine, which Bowen owns, posited that there were so many sinkholes on the floor of the Gulf of Mexico that if it were possible to drain it, “it would probably look like Swiss cheese”.

The excitement comes from the idea that this is exploration. We don’t know what we will see down there, biologically and chemically

Nearly 30 years later, scientists still don’t know just how porous it is.

Culter says scientists have verified about 20 underwater sinkholes on the west coast of Florida alone, but there are probably twice that number. Part of what makes them hard to count is also what makes them so intriguing, says Emily Hall, a scientist at Mote Marine Laboratory leading the mission: They are difficult to spot from above.

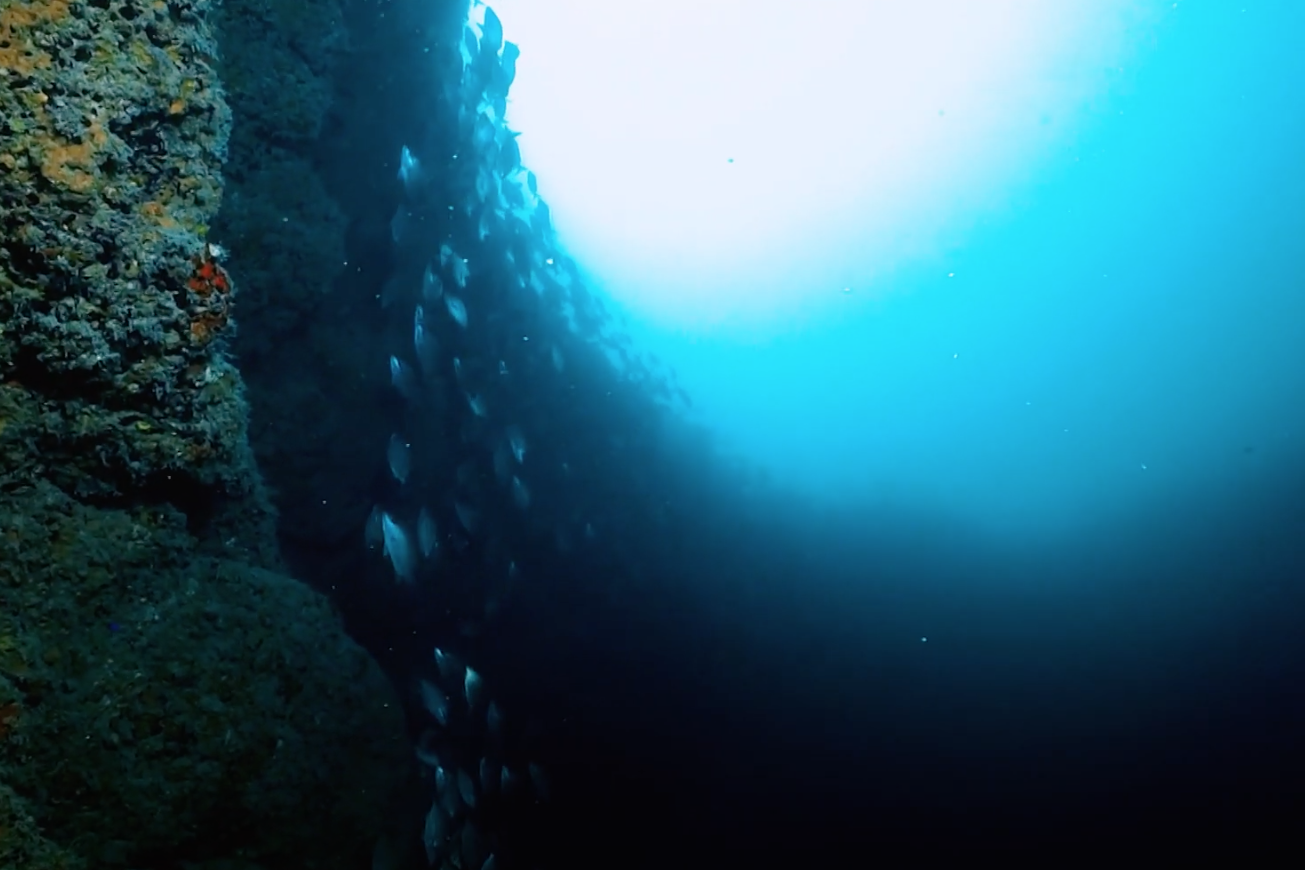

“You’re in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico and you don’t see anything all around,” Hall says. And then, after diving for quite some time, “This hole opens up, and it’s booming with life.”

There seems to be something about the unusual seawater chemistry in blue holes that is particularly good at facilitating life. Pools of fish, oodles of sponges and an array of plants are common within these “oases”, as Hall calls them. The water inside is also often atypically clear, which is part of why they are beloved by divers.

One reason that so little is known about them, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is that their entry points are often narrow — before they broaden out — making it impossible for an automated submersible to enter.

In this month’s mission, which NOAA is funding, the plan is to carefully lower a 600-pound lander inside. The lander, shaped like a triangular prism, and divers will collect water and sediment samples and complete a biological survey, Hall says.

“The excitement comes from the idea that this is exploration. We don’t know what we will see down there, biologically and chemically,” she says. “We have an idea. But every time we go down there, we find something new.”

The team recently explored a nearby blue hole, around 350 feet deep, known as Amberjack. They were surprised to discover two dead smalltooth sawfish, an endangered species, at the bottom.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments