First ever photo of black hole revealed by astronomers, changing our understanding of the entire universe

53 million light years from Earth, 6 billion times the mass of our sun and, until now, never before seen by humanity

The first ever photo of a black hole has been revealed by scientists.

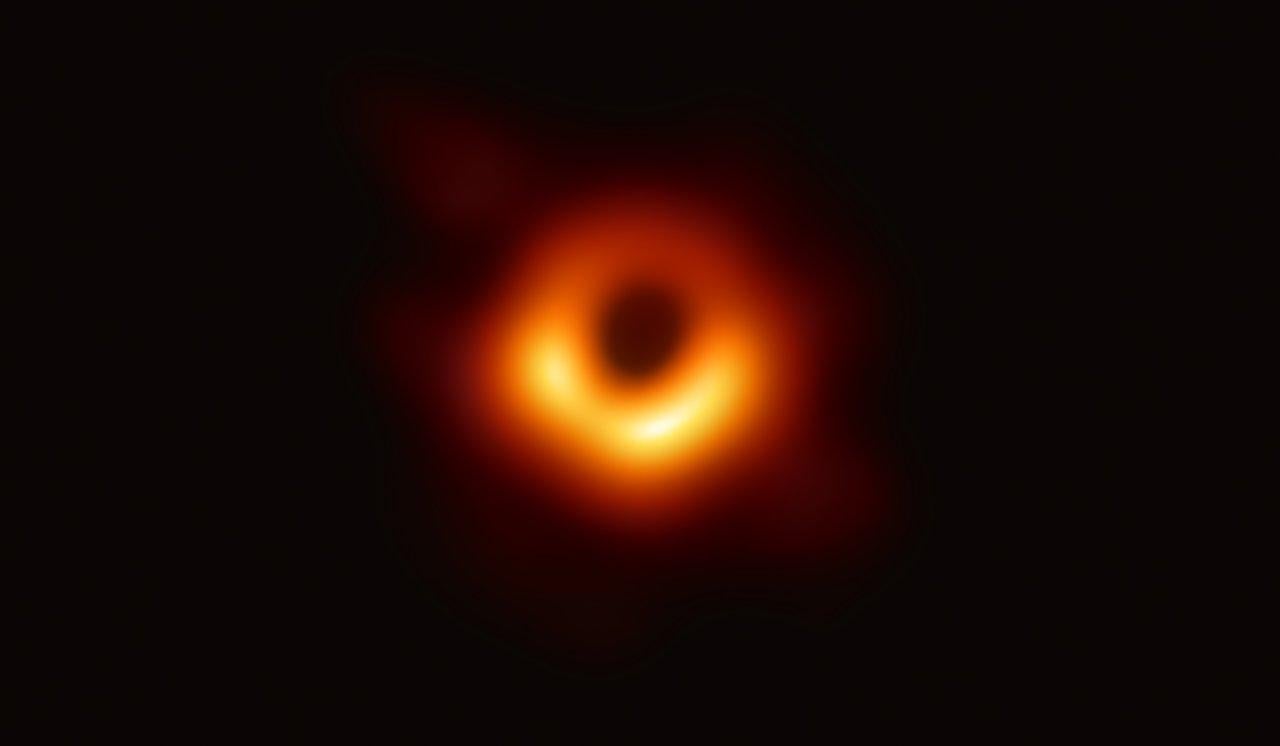

The stunning image, showing a flaming ring of yellow and red, helped advance our understanding of the universe.

Black holes are among the most massive and powerful phenomena in the known universe. But until now, we have not been able to see them because they drag in light.

“We have seen what we thought was unseeable,” said Sheperd Doeleman of Harvard. “We have seen and taken a picture of a black hole.”

Jessica Dempsey, a co-discoverer from the East Asian Observatory in Hawaii, said that when she first saw the image, taken two years ago, it reminded her of the powerful flaming Eye of Sauron from Lord of the Rings.

Unlike smaller black holes that come from collapsed stars, supermassive black holes are mysterious in origin. Situated at the centre of most galaxies, including ours, they are so dense that nothing, not even light, can escape their gravitational pull. This one’s “event horizon” – the point of no return around it, where light and matter begin to fall inexorably into the abyss – is as big as our entire solar system.

Three years ago, scientists were able to hear the sound of two much smaller black holes merging to create a gravitational wave, as Albert Einstein predicted. The new image, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, adds light to that sound.

Outside scientists suggested the achievement could be worthy of a Nobel Prize, just as the gravitational wave discovery was.

While much of what surrounds a black hole falls into a death spiral and is never to be seen again, the new image captures “lucky gas and dust” circling at just far enough to be safe and seen millions of years later on Earth, Dempsey said.

Taken over four days when astronomers had “to have the perfect weather all across the world and literally all the stars had to align”, the image helps confirm Einstein’s general relativity theory, Dempsey said. Einstein a century ago even predicted the symmetrical shape that scientists just found, she said.

“It’s circular, but on one side the light is brighter,” Dempsey said. That’s because that light is approaching Earth.

The measurements are taken at a wavelength the human eye cannot see, so the astronomers added colour to the image. They chose “exquisite gold because this light is so hot”, Dempsey said. “Making it these warm gold and oranges makes sense.”

What the image shows is gas heated to millions of degrees by the friction of ever-stronger gravity, scientists said. And that gravity creates an effect where you see light from both behind the black hole and behind you as the light curves and circles around the black hole itself, said astronomer Avi Loeb, director of the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard.

The project cost around £40m, with half of that coming from the US National Science Foundation.

Astrophysicist Ethan Vishniac, of Johns Hopkins University in Maryland in the US, pronounced the image “an amazing technical achievement” that “gives us a glimpse of gravity in its most extreme manifestation.”

He added: “Pictures from computer simulations can be very pretty, but there’s literally nothing like a picture of the real universe, however fuzzy and monochromatic.”

“It’s just seriously cool,” said John Kormendy, a University of Texas astronomer. “To see the stuff going down the tubes so to speak, to see it firsthand. The mystique of black holes in the community is very substantial. That mystique is going to be made more real.”

There is a myth that says a black hole would rip you apart, but Loeb and Kormendy said the one pictured is so big, someone could fall into it and not be ripped apart.

Black holes are “like the walls of a prison” said Loeb. “Once you cross it, you will never be able to get out and you will never be able to communicate.”

The first image is of a black hole in a galaxy called M87 that is about 53 million light years from Earth. One light year is 5.9 trillion miles, or 9.5 trillion kilometres. This black hole is about 6 billion times the mass of our sun.

The telescope data was gathered by the Event Horizon Telescope two years ago. Completing the image involved about 200 scientists, supercomputers and hundreds of terabytes of data delivered worldwide by plane.

The team looked at two supermassive black holes, the M87 and the one at the centre of the Milky Way. The one in our galaxy is closer but much smaller, so they both look the same size in the sky. But the more distant one was easier to take pictures of because it rotates more slowly, Dempsey said.

“We’ve been hunting this for a long time,” Dempsey said. “We’ve been getting closer and closer with better technology.”

Additional reporting by agencies

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks