The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Arm: The hidden tech giant powering the rise of Apple’s iPhone

Arm has achieved indispensable status: 13 million software engineers write code that runs on its chips, and it sits at the heart of the iPhone while remaining largely in the background. Now it is coming into public view with a planned blockbuster public listing in America, reports James Ashton

Apple is the most recognisable consumer brand of the age, an electronics juggernaut whose phones and computers redefined their categories and crushed the competition. But world-beating success has been powered in part by a low-profile, surprisingly ubiquitous company that plays a key role in its partner’s success.

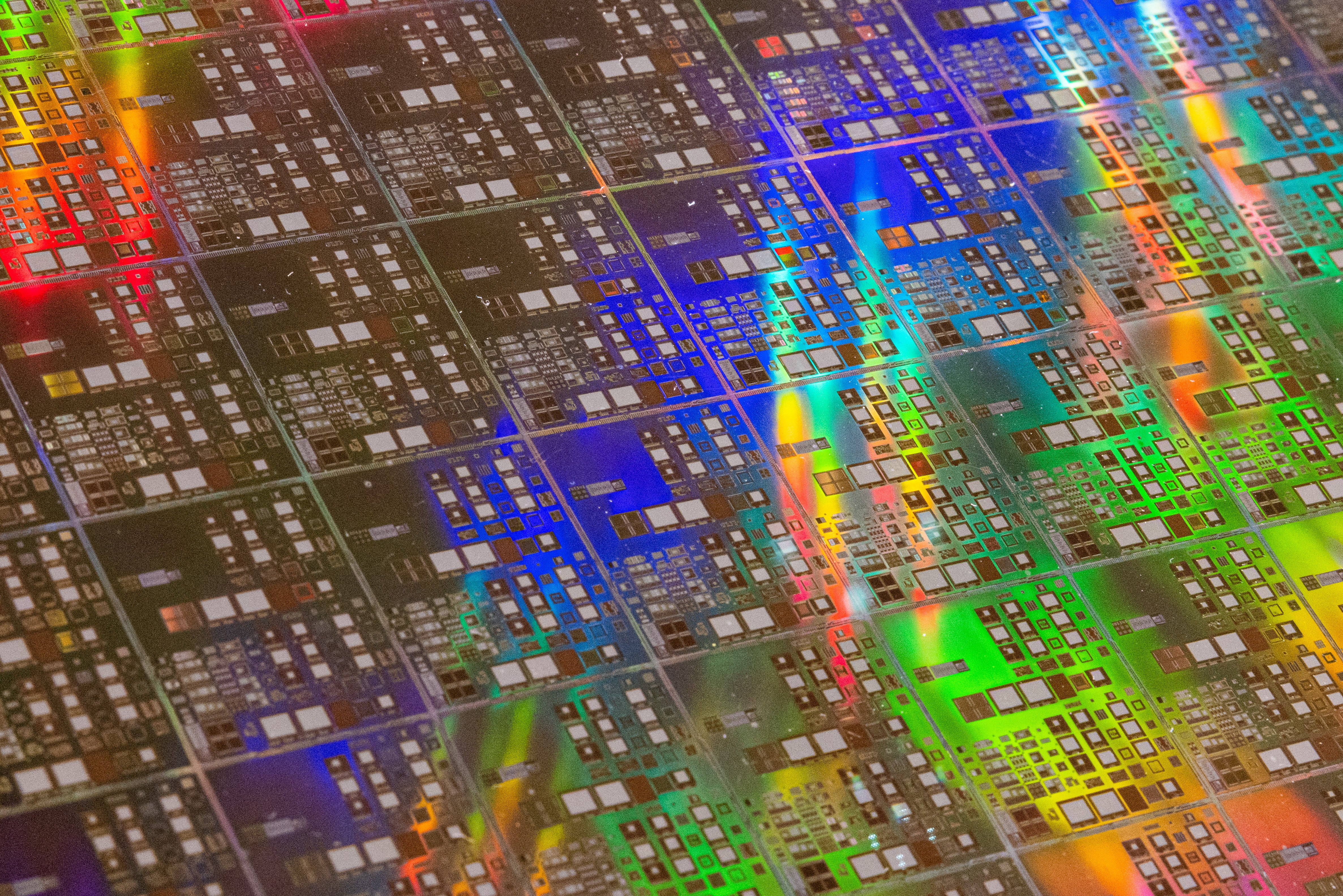

Apple sold something like 300 million iPhones and iPads last year. Every one of them is powered by processors built on designs created by Arm, a British chip company. It has licensed its blueprints an astonishing 30 billion times – not only for Apple devices but for laptops, industrial sensors, cars and computer servers.

In recent years, as more and more devices have become smart and require more and more microchips, Arm’s business has flourished. The company’s volumes have doubled in six years.

This autumn, interest in Arm may even briefly eclipse Apple on Wall Street, where its Japanese owner SoftBank aims to raise up to $10bn from a listing that could spark a revival for new issues if it goes well. And in a transaction that might value Arm at $70bn, Apple may once again become a cornerstone investor, just as it did at the beginning of their relationship when Arm was founded more than three decades ago.

Arm’s secret sauce is a rulebook, otherwise known as an instruction set architecture (ISA). This digital-era Ten Commandments comprises a few thousand instructions that can be configured into four billion possible encodings. They determine how a microchip’s central processing unit (CPU) – the “brains” of the device – is controlled by software.

As the semiconductor industry has become fiendishly complicated, chipmakers have opted to buy in ideas rather than design everything themselves. Just like building a skyscraper, packing billions of transistors onto a sliver of silicon, repeated layer on layer, requires a floorplan. Hence Arm’s designs, which it sells for a few cents a time, became a must-have.

The ISA’s predictability helps software developers write more efficient code. Its simplicity means the processing system operates at low power – a vital attribute in the energy-sapping world of electronics where demand for greater performance and more functionality only increases with time.

Apple has always been troubled by issues of efficiency and price, and that concern was the basis of its relationship with Arm from the beginning. Rewind to 1990, in the years following co-founder Steve Jobs’ departure, when the company was looking beyond the Macintosh computer to new growth markets. Many years before the iPhone was dreamt up, Apple was on the hunt for a better processor for a portable device that was under development. The chips designed by the mighty American telecoms company AT&T for what was known as the Newton were too costly and lacked power.

By a circuitous route, Apple discovered a project under way across the Atlantic at Acorn, the Cambridge-based business that was a one-time rival in the home computer market. To leapfrog its pack of competitors, Acorn’s top engineers had come up with a stripped-down processor – the Acorn RISC Machine (ARM) – which delivered 25 times the performance of the top-selling BBC Micro computer that had made Acorn’s fortune. The trouble was it didn’t have the money to exploit its potential.

For a modest $2.5m (then £1.5m), Apple struck a joint venture with Acorn to give the retitled Advanced RISC Machines its independence. To keep costs down, it set up shop in a 17th-century barn in a village several miles outside Cambridge. The deal was championed by Larry Tesler, Apple’s chief scientist and creator of the cut, copy and paste function, who joined Arm’s board.

Incidentally, RISC stood for reduced instruction-set computer, a processor genre that acknowledged that 80 per cent of the time a chip used just 20 per cent of its instructions, so the rest could be dropped and tasks were broken down into a handful of simple instructions instead.

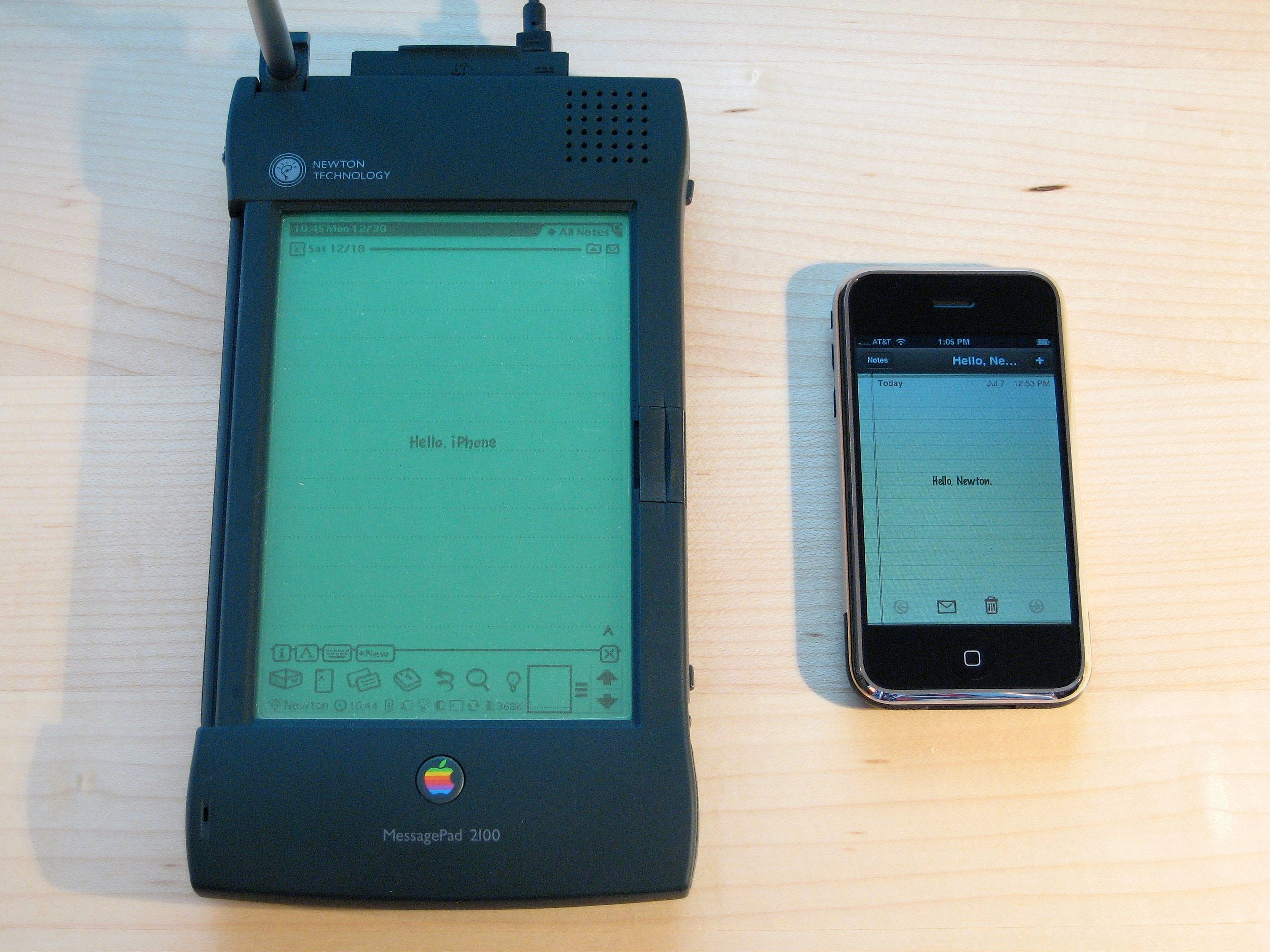

Three years on, Arm designs appeared in Apple’s Newton device, which was branded MessagePad and chiefly remembered for its patchy handwriting software and its plastic stylus used for jotting down notes on screen. But the return of Jobs to Apple in 1997 sounded the Newton’s death knell.

Apple was far from the behemoth it is today. It needed cash before it could spend heavily on big new ideas. Fortunately, Arm could help in that department too. After some fallow years, the company’s fortunes were transformed when its designs found a home in Nokia’s mobile phones, reducing energy consumption to the extent that batteries could be shrunk and handsets became truly pocket-sized. The following year, Arm floated its shares in London and New York, achieving a $1bn valuation on their debut.

It was handy timing for Apple. When Jobs began to reassert his grip on the business in the autumn of 1997, cash reserves had shrunk to $1.4bn and its debt rating – an indicator of a company’s cost of borrowing – had junk status. That October, it was cut again by the credit ratings agency Standard and Poor’s.

Jobs negotiated a $150m injection from Apple’s old foe Microsoft, but by selling its Arm shares gradually until 2003, it earned another $838m to tide it over. In an interview before his death, Tesler admitted: “The most successful part of the Newton project was the Arm,” adding that: “We made more money off the Arm from our stock than we lost on the Newton.”

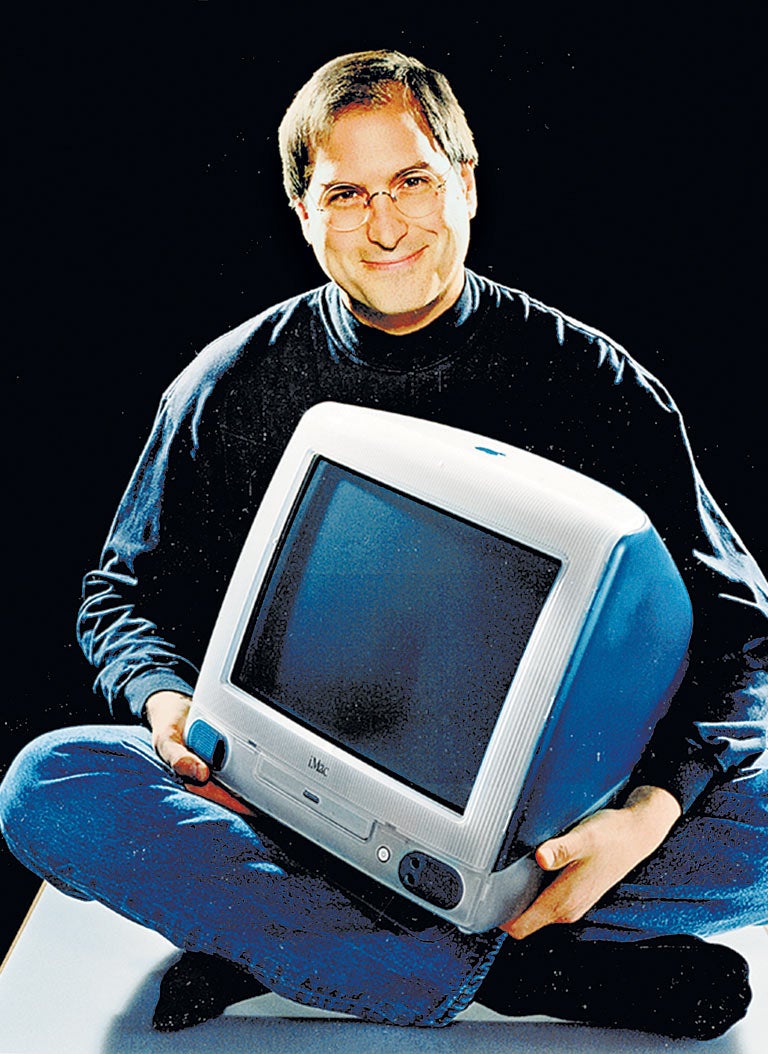

By that point, the second phase of Apple and Arm’s relationship had begun. Apple’s reboot kicked off in 1998 with the iMac, a futuristic, egg-shaped Macintosh computer, the first product to carry the imprint of the British designer Jony Ive. Then came ambitions for a music device to trump the crop of MP3 players that were already on the market.

To lead development, Apple hired Tony Fadell, a headstrong computer programmer and rock’n’roll fan who had grown up listening to Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones and Aerosmith. In the rush to get what would become the iPod to market in time for Christmas 2001, employing Arm’s technology once again appeared to have been purely coincidental. Fadell hunted for a company whose work could provide a base for the new device and settled on PortalPlayer, a Santa Clara-based start-up that had adopted the variety of Arm designs first developed for Nokia.

Despite strong overtures from US chip giant Intel, which began supplying the chips for the Macintosh computer in 2005, Apple stuck with Arm for the iPhone that launched in 2007, as well as 2010’s iPad. As Arm sought new partners and to develop new applications for its ISA, it was a powerful calling card.

Even better news came in 2020 when Jobs’s successor, Tim Cook, announced that the technology giant was dropping Intel chips from the Mac in favour of “Apple silicon”, its own in-house chips developed on Arm architecture – signalling the third phase of the pair’s collaboration.

From focusing on the look and feel of its products, Apple calculated that microchips had become a huge differentiator to its business and too important to leave to the microchip industry alone. Apple wanted to build the chips itself. Over more than a decade it has set about becoming a fully-fledged semiconductor designer, producing its own chips to handle cameras, AI, and for its watches, TVs and headphones.

It has done so by acquisition, recruitment and the assembly of a portfolio of thousands of wireless technology patents, ranging from protocols for cellular standards to modem architecture and operation. As it has reduced its reliance on industry giants Intel and Samsung – and now Qualcomm – people who know Apple well estimate it employs at least 4,000 chip engineers.

But alongside Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC), the expert chipmaker, it has maintained and indeed tightened its relationship with Arm. In 2008, Apple requested an architecture licence from Arm, which meant it could significantly vary its own designs from Arm’s blueprints rather than just license the standard building blocks. It was a key plank in Apple’s plan to take greater control of its destiny. At that stage, Arm had only granted a handful of such licences, and all to traditional chip companies. More would follow.

Today, billions of dollars have been expended on the race to be different across numerous product categories. But every microchip designer, whether a long-standing player or relative newcomer to the field – including Apple, Amazon, Samsung, Qualcomm, Google, Huawei, Alibaba, Meta and Tesla – has Arm in common.

These digital titans have gone to great lengths to outsmart each other, hiring the best designers and buying firms with the leading intellectual property. But jettisoning external suppliers has not yet extended to dropping Arm – although RISC-V, a royalty-free alternative, is growing fast. For now, Arm’s architecture is too complicated and cost-effective to reinvent and, anyway, the industry has invested too much in it.

This importance explains what the fourth phase of Arm’s relationship with Apple could look like – and the difficulty in getting there. The heavily indebted SoftBank has been trying for four years to sell some or part of Arm. A lucrative combination with the AI chip specialist Nvidia was blocked by regulators after its other major customers complained they would be put at a disadvantage. For the same reason, historic speculation that Apple would one day acquire Arm has always looked wide of the mark.

Arm, a kind of “Switzerland of semiconductors”, has achieved indispensable status. Some 13 million software engineers around the world write code that runs on its chips, which shows up on iPhones and other devices every day. Everyone wants to own a piece of Arm – but to date, no one can agree how.

To underpin the share price, SoftBank is trying to entice some of its biggest customers to become significant investors as Arm’s stock is sold on the Nasdaq this autumn. Many have worked with the company for years – but none has the shared history that Arm has with Apple.

James Ashton’s book, ‘The Everything Blueprint: The Microchip Design That Changed the World’, is published in the US on September 26. It can be pre-ordered now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks