Are airships on the rise again?

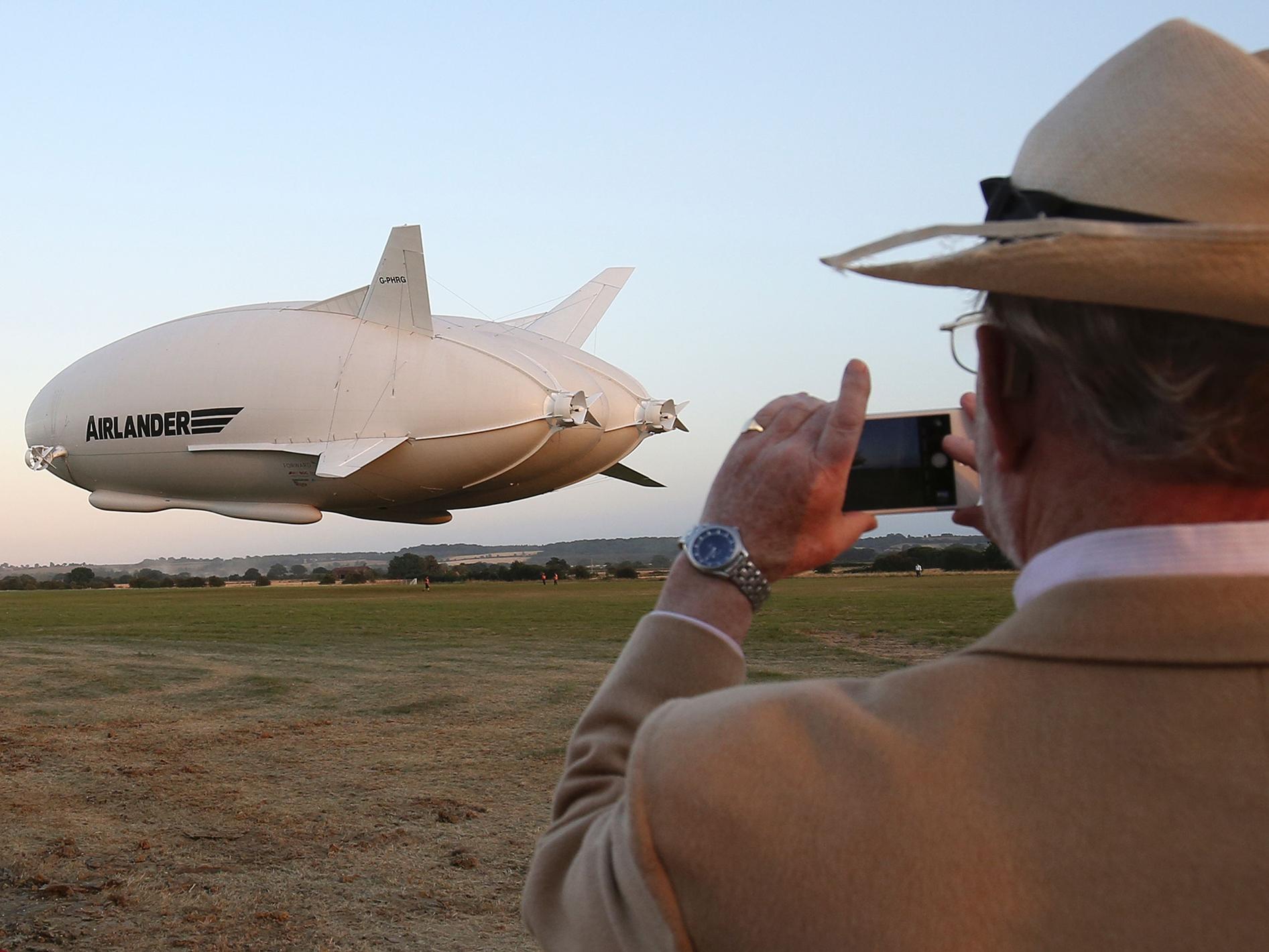

While images of the Hindenburg crash still torment the collective memory of the airship, Steven Cutts asks if Airlander 10 could change our minds and become the future

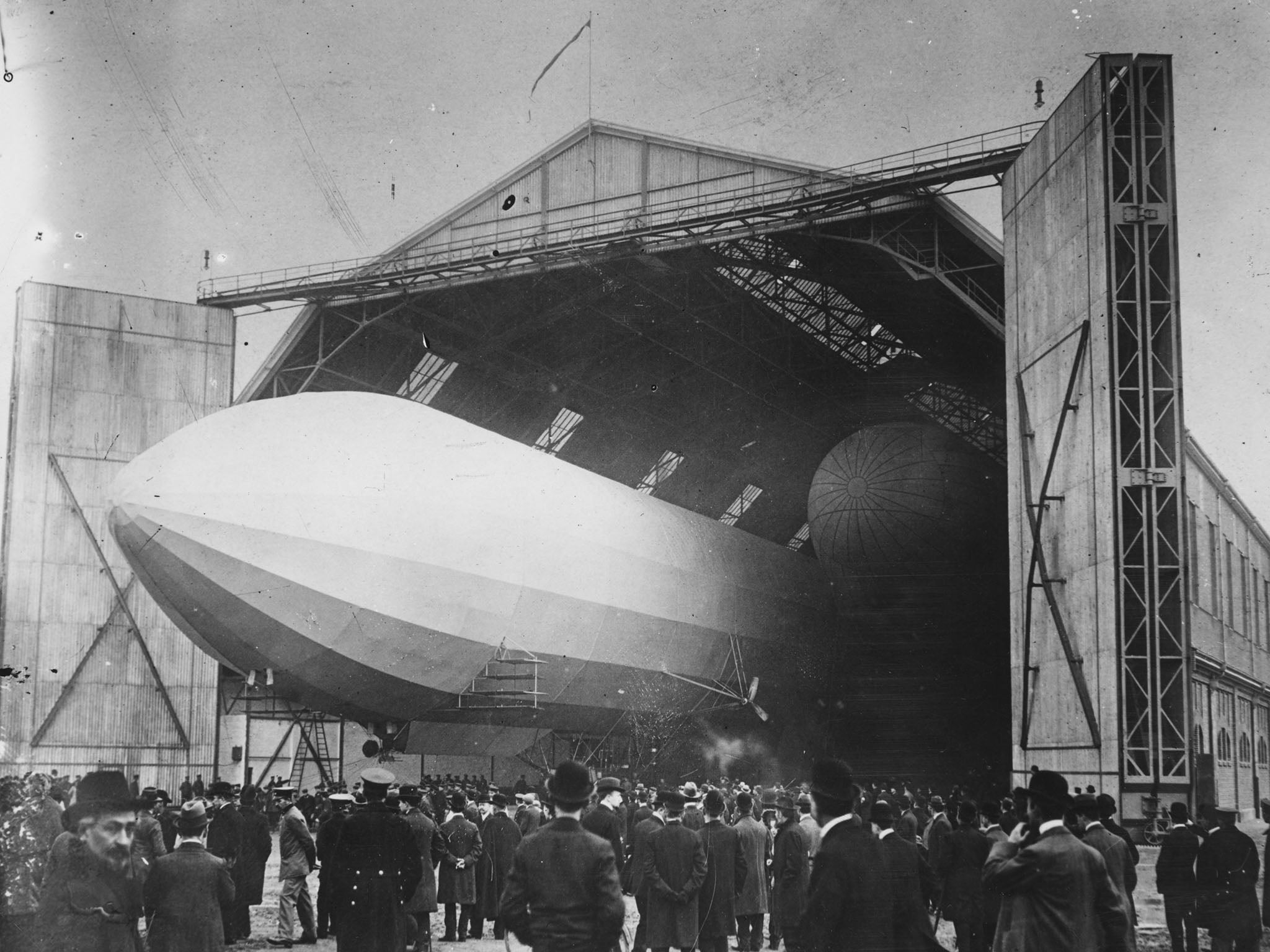

A concept that was once consigned to the engineering litter bin is about to be rediscovered. The airship is looking to make a comeback and there are several nations – including our own – trying to cash in. Although men have dreamt of flight since antiquity, it wasn’t until quite late in the 18th century that the first balloons carried a small number of people to high altitude. Most of them worked on hot air and this kind of flight is referred to as lighter-than-air transport.

A hundred years later, hot air balloons were a reasonably common sight but many experts felt that heavier-than-air transport was still a fantasy. Then, incredibly, a couple of bicycle repairmen in the US proved them all wrong, taking it in turns to fly their prototype vehicle off the beach in Kitty Hawk.

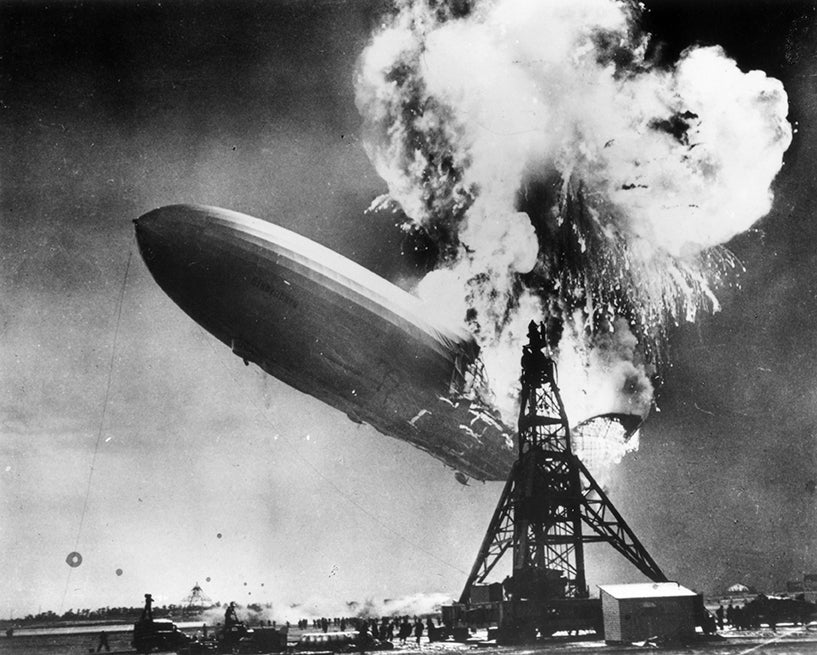

Overnight, the Wright Brothers changed everything, but besides heavier-than-air transport, they had also opened the minds of men to a machine that could move through the Earth’s atmosphere using propellers. Concerned about the range and cargo capacity of aircraft, many engineers started to experiment with airships. These were essentially torpedo-shaped balloons that were powered by onboard propellers. This kind of technology probably reached its zenith with the maiden flight of the gigantic luxury airship, the Hindenburg, that flew all the way from Europe to America where it managed to catch fire and explode.

Quite a lot of the Hindenburg was built out of animal skins and if we decided to revisit that technology now, we could use some much better materials with a much lower risk of failure. But the political and folk memory of the Hindenburg disaster isn’t going anywhere fast and both the public and legislators remain sceptical of a hydrogen-based airship.

Right? Well, maybe not. Ever since the 1960s people have been talking about the second coming of the airship and – in the course of the next few years – such an eventuality might just happen.

An airship has several advantages over a conventional aircraft. It can stay aloft for several weeks at a time and it consumes little in the way of fuel. It has the potential to take off and land vertically and shows no prejudice between a formal airfield or an unprepared lake or meadow. Landing on fresh snow is entirely possible in an airship.

With this in mind, the massive British aircraft Airlander 10 is currently being built by Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) in the UK. Airlander 10 is officially the largest aircraft in the world and has already been sent on several test flights. Their original design was intended to perform aerial reconnaissance missions for the US military. In an environment such as Afghanistan, the enemy is unlikely to have access to long-range anti-aircraft missiles or fighter planes and while a huge object like an airship might look like a sitting duck, its ability to fly at very high altitude would probably have kept it safe. Shortly after the first test flight, the Pentagon withdrew its support and a group of British engineers bought the prototype for the bargain price of $250,000. Later on, they managed to reboot the entire project in Bedfordshire, culminating in a series of colourful test flights, at least one of which ended in near disaster. Several months later and after a significant redesign, it crashed again, this time without any crew on board.

Artificial intelligence is rapidly approaching the point where it could drive an ordinary car down an ordinary road; the challenge of navigating the jet stream is quite minor in comparison. The immense, very high altitude airships of the future will function as autonomous drones

If it ever works properly, Airlander 10 could carry 10 tons of cargo. There are quite a lot of scenarios where 10 tons would be regarded as a commercially significant load. Oil exploration companies find themselves drilling in some very remote locations and their operating costs are often bloated by the need to build a purpose-built road. If the crew and drilling equipment could be delivered by air, then the price of an entire road could be struck off the balance sheet. Most experts believe that an airship would have much lower operating costs than a helicopter and this makes them doubly attractive.

So what’s the downside? Well, some people have asked fundamental questions about the availability of helium gas. Helium is completely inert which makes an onboard fire virtually impossible, but it isn’t the easiest substance to get your hands on. If we tried to really fill the skies with helium-filled airships, might not the total supply of helium run dry? Remember that we could always switch back to hydrogen, which has 30 per cent more lifting capability than helium and is a lot cheaper, but again, memories of the Hindenburg disaster are still present in the popular imagination and for the time being, any attempt to build a new airship is going to be based on the inert gas, helium.

Remember that airships were also defeated by fixed-wing aircraft and these have now achieved a remarkable safety rate. Even though the number of aircraft flying in the world forever increases, there are surprisingly few accidents. In 2017, (the safest year on record) only 44 lives were lost to airline accidents. The public has faith in aircraft but they don’t have faith in airships. If just one example of the next generation airship crashes with any significant loss of life, the entire industry will crash with it.

More recently, the British government has given a grant to the HAV to try to develop a battery-propelled version of Airlander 10. Technologies that don’t require fossil fuels are all the rage right now but there are potential benefits that go beyond global warming. An electrically powered Airlander would have the advantage of being almost completely silent, enabling it to fly over densely populated areas at night. On the downside, top speed would be less than 100 miles per hour and electric propulsion might decrease the operational range.

Sounds exciting? Well, yes, it is. The people watching the Airlander 10 test flights were all on edge and from the right angle, it looks like Thunderbird 2 come true. But it’s not easy to predict how quickly this particular future will be upon us

One major problem with the airships of old was landing. Because airships are lighter than air, they have a tendency to bob up and down when they approach the Earth’s surface. There are plenty of occasions where men on the ground struggled with ropes to secure some runaway balloon in a mild crosswind.

Most of the next generation of airships are described as hybrid aircraft where the central balloon section has been configured as a gigantic wing. The actual airship isn’t quite buoyant enough to take off and can only fly with the help of engines. Once it gets moving, the Earth’s atmosphere starts to flow above and below the fuselage and the entire vehicle functions as a wing. The positive side of this is that you can always be sure of a good landing. If you cut your speed and stop any vertical thrust, the strength of the Earth’s gravity is guaranteed to bring you down, albeit rather slowly in the case of a fully inflated airship.

Some design teams are looking even further into the future, imagining a world where ocean-going ships are all but abandoned and cargo can be transported through the skies using supermassive airships and almost no fuel.

The jet stream is a wind that blows from west to east, more or less round the clock. It is driven by the rotation of the Earth and the heat from the Sun and if you want to emulate Richard Branson and fly around the world in a balloon, the best way to do it is to ascend to high altitude and wait for the jet stream to catch you. If you cast your mind back a few years, several teams were attempting to circumnavigate the world in a balloon. They were all managing to fly at well over 100 miles per hour in spite of the fact that they didn’t have any engines. All of these balloons had allowed themselves to be captured by the jet stream.

Other researchers are now considering airborne freighters that would carry huge cargos around the world, always flying due east. Such machines would be more than 1,000 metres long. In this scenario, a massive hydrogen-filled airship might take off from England and ascend towards the jet stream. (You’d need to be about 10,000 to 20,000 meters up.) Once there, the airship combines the thrust from onboard engines with forces of nature and eventually descends over Japan. Back on ground level, it receives a new cargo and reascends, back into the jet stream using fuel and engines primarily for steering until it lands again, this time on the west coast of the US. A few days later, it returns to the UK across the midwest and then the Atlantic. Cruising speed is about 150 miles per hour, much less than the 400 to 500 miles an hour we’d expect from a conventional airliner, but vastly superior to the speed of an ocean-going boat and without concern for canals, rocks or national borders.

This kind of technology would require hydrogen-filled balloons which reintroduces the risk of an explosion, but some engineers are confident that new materials and technologies would be capable of negating the risk of fire. By the time these machines were flying, it is unlikely that they would require a human crew. Artificial intelligence is rapidly approaching the point where it could drive an ordinary car down an ordinary road; the challenge of navigating the jet stream is quite minor in comparison. The immense, very high altitude airships of the future will function as autonomous drones

Such advances might also downgrade the carbon footprint associated with global trade whilst actually speeding up the flow of goods. It is, however, critically dependent on our willingness to accept the idea of a vast hydrogen-filled balloon, circling over our heads on a daily basis.

Even as you read these words there are engineers in France, Germany and China working on exactly these concepts. Some of them are actually cutting metal. The legendary American company Lockheed Martin is in the process of building its own prototype and has actually signed contracts with aviation companies to deliver a flight-ready aircraft.

Sounds exciting? Well, yes, it is. The people watching the Airlander 10 test flights were all on edge and from the right angle, it looks like Thunderbird 2 come true. But it’s not easy to predict how quickly this particular future will be upon us. A comeback fight for the airship has been mulled over for nearly as long as the sequel to Top Gun and it still hasn’t happened. Even with computer-aided design and simulation, there’s no guarantee that any of these concepts will be viable in our lifetimes. The atmosphere is a cruel and unforgiving place and the Earth’s gravitational field isn’t going away. In just a handful of carefully planned test flights, the Airlander team managed to crash twice. Aerospace research isn’t any more predictable now than it was in the days of the Wright Brothers and neither are the risks.

So watch this space and don’t hold your breath.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments