Ahead of the game: Sony's PlayStation convinced us that video games are more than just child's play

Friday sees the launch of the PlayStation4. In the almost 20 years since its first incarnation, gaming has changed beyond recognition and it's thanks, in part, to the fact that the console was aimed at adults

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Compare these two adverts. In October 1992, Nintendo proudly tells British gamers about the arrival of the SNES (Super Nintendo Entertainment System). To a throbbing accompaniment, a clean-cut youth materialises in a virtual-reality arena that owes something to The Running Man.

"You are about to experience the future!" a booming voice proclaims, reverberating around the chamber as our hero spins through a series of screenshots. "Never before have you had to cope with advanced 3D graphics!" The gamer's head spins 360 degrees. Then he is dressed up as a robot.

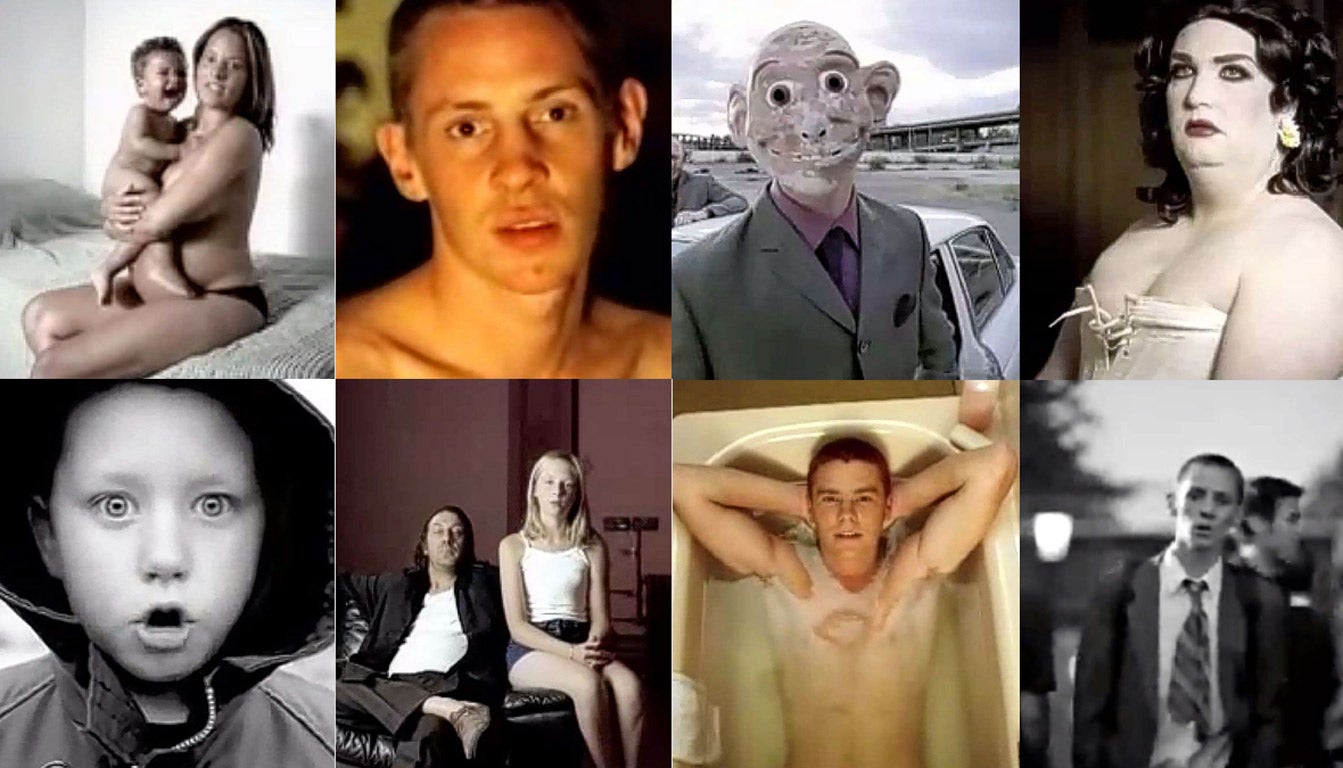

Then there's "Double Life", an ad which appeared on our screens in 1999 and in which a series of eccentric individuals deliver a kind of monologue relay describing what they get up to in their free time. "I won't deny I've engaged in violence," says a dubious looking hard nut. "You may not think it to look at me," says a battleaxe transvestite; a skinhead woman and bug-eyed child continue: "I have commanded armies, and conquered worlds." Fauré's Requiem plays in the background. There are no robots, no Europop, no gameplay footage. This is an ad for the PlayStation.

As the PS4 launches, and a new branding battle for gamers' loyalty begins, Double Life still feels bold. In 1999, four years after the PlayStation first launched, gamers were still a species of bedroom-dwelling ne'er-do-wells with no place in adult society, and you might even have called the ad radical. And it pointed to a branding insight that defined a new era, setting the scene for a change in the video games market. "Since then, it has gone from teenage geeks to something that's accessible to everyone," says Stephen Cheliotis, chairman of the Superbrands council.

In the 1990s, though, the aim was not to appeal to everyone, it was to give the hopelessly lame video-games market some limited flavour of cool. As the Nintendo 64 maintained its focus on the core audience, Sony spotted an opportunity. "They quite cannily noticed that a lot of people in the market were actually in their teens and twenties, not children," says Alex Wiltshire, a video-games writer who used to edit Edge magazine. "They were the people who had played on their Spectrums in the Eighties, and they were still interested."

From the very beginning, the PlayStation, which went on sale in December 1994, felt different. "The competitors were skewed towards kids," says David Wilson, head of PR for Sony's UK games division. "Sega and Nintendo had these platform, cartoon-character driven games, and Mario vs Sonic was everything. To begin with, PlayStation didn't have a mascot in that way."

What it did have was Wipeout, a trippily futuristic racing game that chimed more with the era's club culture than it did with anything produced by Disney. A sense of what the developers were on to came in the 1995 cyber thriller Hackers, which featured Angelina Jolie and Jonny Lee Miller playing the game at a rave; meanwhile, real clubs were installing consoles for their clientele.

Most of Sony's marketing efforts followed the same approach, in a formula the games writer Simon Parkin calls "exciting, provocative and, at times, appropriately transgressive". At Glastonbury one year, they handed out PlayStation postcards with perforated strips that could be torn off and used as roaches. Even cute Crash Bandicoot wasn't safe: David Wilson recalls that cards were printed up with a phone number and the phrase "Randy Bandy new in town" and put up in phone boxes. Such stunts, Parkin says, were "designed to appeal to mainstream players... They are there to convince people who are interested in music or in cinema." The ultimate aim, he concludes, was to "somehow de-stigmatise games to people who might otherwise be suspicious of their cultural, personal or artistic worth".

Another milestone that counted, at the time, as subversive came in the only character that would be anything like a mascot for the console: Lara Croft. She represented a significant development: a female character in a game doing something other than being saved. "I was 12 when Tomb Raider came out," says games critic Cara Ellison. "It was an important threshold that said, hey, this is for you as well. I'd never seen a heroine like that before – I started to think about consoles as something that grownups would have." Sure enough, in 1997, Ms Croft appeared on the cover of The Face – a defining venue for cool of the era.

It was in such an atmosphere that ad agency TBWA started work on Double Life. Copywriter James Sinclair recalls working on the commercial with creative director Trevor Beattie: "It was one of the best things we ever did. The brand was so exciting. The idea of 'lives' in games, that you lost one and you got another one, that there were no consequences, was just brilliant."

Interestingly, he suggests that the sophistication of the pitch may partly have been forced by circumstance. "We wanted to do anything we could to avoid having the games in the ad because they looked so fake, they broke the spell. Their power was all about imagination. It's like looking at photos of your holiday or a big night out. It was a great night, a great holiday, but when you look at the pictures and you're not engaged in the experience, they don't work."

As the console matured, and was ultimately superseded by the PS2 in 2000, the flow of edgy branding exercises continued; some of the results were appalling. The internet overflows with slideshows of infantile PlayStation ads from across the world – sexist, racist, and just plain unpleasant alike. Sometimes, too, the attempts at counterculture have caused a backlash, as when graffiti artists across America took offence at Sony's crass invasion of their territory with some Banksy-inspired versions of the PlayStation Portable.

More recently, the PS3 and now PS4 have tried to move the console still further "out of the gaming ghetto", as David Wilson puts it. To do so, they have downplayed the youth culture pitch in favour of a more family-orientated approach that has arguably diminished its brand across the board. "They've followed this trajectory that has led to the console being completely blandified – you can't pin any cultural identity on it at all," says Alex Wiltshire.

One reason is that the PlayStation has gone from maverick fringe product to one of the key pillars of Sony's strategy, which makes risks harder to justify. Another, Wiltshire points out, may be the inevitable maturation of the wider market. Those Spectrum players are in their late thirties now; they want to play games with their kids. Besides, nobody tries to sell DVD players or televisions by emphasizing their identity – instead, they leave that to the content. "Game culture has matured massively," Wiltshire suggests. "You have a far greater gamut of meaning among titles than you ever had before. If you're interested in arty games, you have that. If you want violent games, you have that." Perhaps the console itself doesn't need a persona any more.

Despite that reduction in mischief-making, Sony still feels a little bit different. Players are connected to this history, so much so that one of the most widely watched pieces of PlayStation publicity on YouTube this year is a video that shows the console's evolution over the last two decades through a single front room.

Meanwhile, launch ads for the PS4 and Microsoft's Xbox One have been running online for a while. In Microsoft's ad, the likes of Steven Gerrard and Star Trek's Zachary Quinto invite you to join them in a multimedia paradise, where game-playing is just one of a range of family-friendly activities engaged in by a self-consciously diverse selection of consumers. The PS4 ad, in contrast, features no celebrities – just spaceships and car chases and gunfights. "This," the narrator shouts, "is for the players."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments