Medicine and economics graduates are the highest-paid in the UK, study finds

Concern emerges the statistics are 'rife with inequalities' as ongoing gender pay gap is brought to light

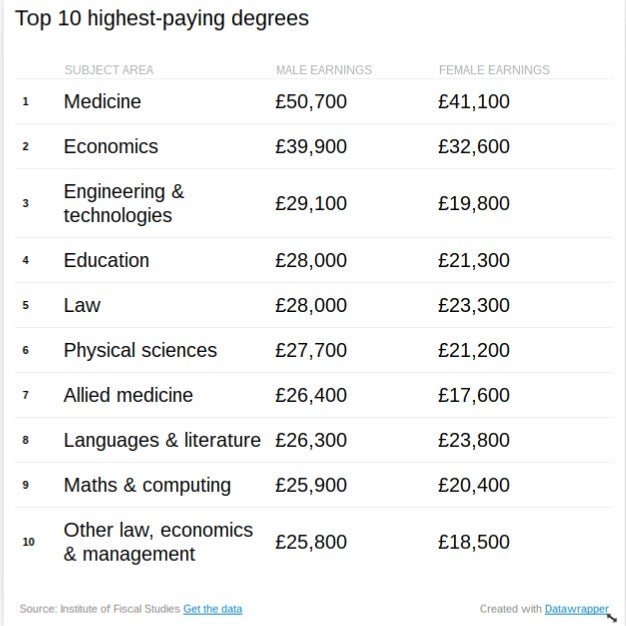

Working professionals with degrees in medicine and economics have emerged as being, on average, the highest-earning graduates in the country ten years after leaving university.

Male medical grads are earning an average amount of just over £50,000, while former male economics students are taking home around £40,000 each year, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies’ (IFS) study into graduate earnings.

Despite still being among the highest-paid category, female medical professionals, on the other hand, are earning just over £41,000, and women economics grads are making, on average, £32,600.

Those armed with qualifications in the fields of engineering and technologies, education, and law have gone on to make up the rest of the top five highest-paid graduates.

However, concern has emerged the statistics are “rife with inequalities” as females consistently emerge as being paid less than their male counterparts, even if both studied the same course at the same university.

On average, women graduates are pocketing around £3,000 less each year than men ten years after completing their studies.

Head of the National Union of Students (NUS), Megan Dunn, said the figures are not because women are “not as good as men,” but are, instead, the result of years of sexist and structural oppression that “starts right from birth.”

She said: “Although these statistics are terrible, they come as no surprise. We know from our own research and work with students that women face persistent sexism throughout education - and then in the workplace.

“The gender gap is caused by a range of issues and there is no quick fix. Employers need to be held to account for their equalities practice and provide training for all staff to help overcome these issues.”

At the other end of the spectrum, creative arts grads with degrees in subjects such as dance, drama, art and design, or music, have come out as being, on average, the nation’s lowest-earning. Ten years on from completing their studies, these former students were found to be earning no more than those who didn’t attend university at all.

Male creative arts grads were found to be earning just under £17,000 per year, while females are taking home just £12,400. Those with degrees in veterinary sciences and agriculture-related subjects, as well as mass communication grads, are also among the lowest-paid.

The key result to have emerged from the IFS study, though - which took place over several years - is that graduates from richer backgrounds are earning significantly more after graduation than their poorer counterparts, despite completing the same degrees from the same universities.

Jack Britton, a research economist at the IFS and an author of the paper described the top finding as being “of crucial importance” for policymakers who are trying to tackle social immobility.

He said: “[It] shows the advantages of coming from a high-income family persist for graduates right into the labour market at age 30.”

Addressing the pay gap between rich and poor, Universities Minister, Jo Johnson, said the Government accepted there was still a long way to go to improve social mobility, and added: “We have seen record application rates among students from disadvantaged backgrounds, but this latest analysis reveals the worrying gaps that still exist in graduate outcomes.

“We want to see this information used to improve the experience students are getting across the higher education sector.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks