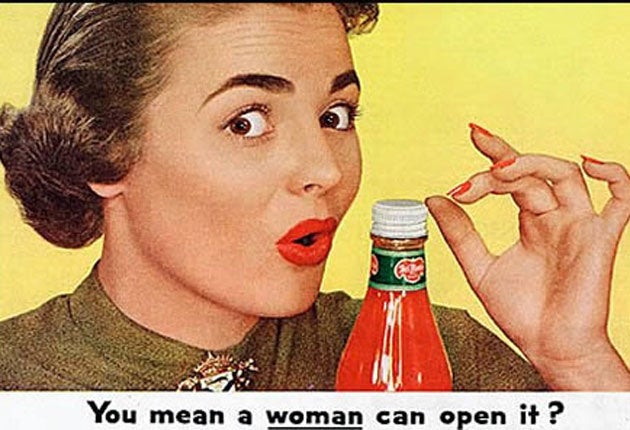

Unfortunately, academic sexism is alive and well

Male academics rarely suffer more than a bit of rudeness, but women have it far worse, according to Luke Brunning

Philosophers have been thinking about harassment and sexism more than usual recently. The Chronicle of Higher Education recently announced the shock departure of the philosopher Colin McGinn from the University of Miami where, philosophically speaking, he was the star player.

McGinn was reported to have resigned following allegations of improper emails to a female graduate student. The boyfriend of the woman concerned reportedly claimed that several of the emails contained sexually explicit content, some pertaining to masturbation.

Instead of undergoing a faculty investigation into his conduct, McGinn is said to have decided to resign after a preliminary inquiry by a university official. He denies any wrongdoing and has not been charged with sexual harassment.

This resignation surprises in several ways. First, a ‘big name’ has resigned; academics rarely resign. Second, and more sadly, many academics are simply surprised if any action was taken in the first place. The position of graduate students is remarkably fragile, especially in subjects like philosophy where women are dramatically underrepresented. A survey by the Society for Women in Philosophy notes that 46 per cent of undergraduates are women, in comparison to 31 per cent of PhD students, and 24 per cent of permanent academic staff.

Finally, McGinn’s response to the matter has caused prolonged discussion In a series of blog posts with ‘context’ as a prevailing theme, McGinn tells us that the allegations followed a close pedagogical relationship with the student as part of the ironic and 'taboo-busting' ‘Genius Project’ which he initiated. This had the aim of improving students’ philosophical abilities through conversation and the occasional game of tennis. The need for this project is perhaps explained by McGinn’s pronouncement that 'graduate students are not what they used to be'.

In the most revealing post, however, McGinn states he has received lots of support from women and proffers an explanation of the controversy shadowing his resignation. He suggests that men leap to conclusions on the basis of poor evidence, or conflate their fantasies with the actions of others, because the male mind 'tends to be crude (in several senses) and dichotomous'. Women, by contrast, 'understand the varieties of human relationships better than men; they appreciate the subtleties and nuances of different kinds of affection between people'. According to McGinn, this explains his support.

This argument, to me, juxtaposes crude and dichotomizing sex and gender essentialism with a subtler contraction, for implicitly McGinn casts himself as subtle and nuanced, and his student as less so (and he claimed that America failed to understand irony…).

Finally, we are told that McGinn values people who are provocative, shocking, and who use irony to jolt people out of complacency within our culture. John Paul Sartre, Phillip Larkin, Martin Amis, and Bertrand Russell are named as inspiring men with characters that stand 'against stifling social norms and dull conformity'. McGinn names no women as sources of inspiration, nor catches the irony in appealing to known misogynists in defending himself against allegations of improper conduct.

The facts surrounding McGinn’s resignation are unclear. But his attitude is not unique. His response is indicative of how far we have to go to tackle allegations of harassment and sexism in academia more generally.

Academic sexism

Academic sexism and harassment is complex, and takes many forms, as is well documented in my subject, philosophy. I am privileged, and only hindered by rudeness, and the crudity that masquerades as academic rigour. But my friends and peers suffer harassment and sexism on a daily basis.

As any Oxford student can tell you, lechery is not extinct. Misogyny, too, thrives and is frequently accompanied with a general hatred of graduate students. Academic sexism, fuelled by implicit bias and the belittling of women as sources of knowledge and expertise, is also rife.

These are familiar categories. But the fallout from McGinn’s resignation, whether the allegations are true or not, prompts me to offer two lesser-known manifestations of insidious academic sexism: the pedagogue and the false-ally.

The mind of the pedagogue is awash with heady thoughts of the good old taboo-busting days. Often they are sexist letches in the possession of sophisticated conceptions of ‘good teaching.’ Pedagogue bingo would include words like: ‘dialogue’, ‘cut and thrust’, ‘rigour’, ‘candid’, ‘enabling promise’, ‘mentoring’, ‘penetrating’, ‘irony’ and so on. Many pedagogues are well intentioned, not explicitly sexist, and certainly not lecherous. Yet their understanding of what it is to do 'good philosophy' or 'good English literature' distorts the prevailing atmosphere in a way that hinders both women and men.

Secondly, we encounter the false ally. This category is particularly egregious because it is possible only because female academics in general, and feminism in particular, are beginning to be valued positively.

For the false ally, the company of female academics, and the chance to be associated with their research, is a tremendous commodity. It has use-value in a changing academic climate where explicit sexism is not tolerated.

False allies bear a self-serving relation to the promotion of female academics’ interests, perhaps due to guilt at their past involvement in their marginalisation. They crave to be seen with female graduates and academics, but do little to promote them in the academy, and pay only marginal attention to the funding and content of their work.

The eagerness of the false ally is counterproductive; their enthusiasm for the promotion of academic conferences, book projects, and administrative initiatives unfurls at the expanse of women who are better pleased to lead, or who have greater expertise. When a ‘big name’ feminist visits, you’ll find the false ally dining alongside her while the researchers most interested or indebted to her work grasp after sandwiches in backrooms.

Campaigns like the Everyday Sexism Project evidence a rising groundswell of opposition to sexism in wider culture. Slowly, similar views are being articulated in academia. It is high time that cleverness and ironising provocation were replaced with a redoubled effort to encourage more female graduates to say in academia. We can worry about creating geniuses at a later date.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks