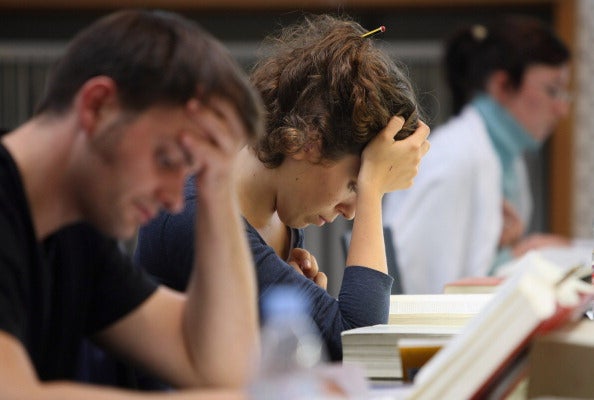

Students, and not just universities, must take responsibility for the success of their studies and career

'I propose potentially severe contractual punishments depending upon the offence; fines, marking down, suspensions, expulsions, and the withholding of degree certificates'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dear student, you’re in. Well done. However, coughing up nine grand a year doesn’t entitle you to a decent degree and job. You have to work for it.

I still owe £18,000, having graduated with a linguistics degree in 2003. A future of signing on, narrowly avoiding a call centre induced lobotomy, and years of poorly paid office work probably didn’t feature in the prospectus.

If I could do it all again, I’d choose a course with an obvious future now, like law, probably at the University of Law as it’s offering a 50 per cent tuition fee rebate to students who don’t get a job nine months after graduation. A cynical marketing ploy? Possibly. A sign of the changing relationship between student and university? Definitely.

Students are paying top-dollar. It’s a buyer’s market. Institutions’ futures ride on them enrolling and doing well at, and after, their studies.

Students are officially customers now and higher education is a business. In this increasingly competitive sector, universities need to up their game to remain attractive. Providing effective careers advice, investing in flashy buildings that adorn marketing literature, and offering study abroad options that meet increased demand is vital.

Universities must provide clear and accurate information to students who are armed with rights, backed by consumer law and unafraid of complaining.

Power rests with students. As an admissions officer, yearly I see students escape their ‘contract’ with their chosen university at the drop of a hat to find another in Clearing. But this kind of power, aided by the student number cap removal that sees many Russell Group universities in Clearing and well-known ones desperately tossing unconditional offers and cash at students, is dangerous. This year’s undergraduates even disregarded the January Ucas deadline, according to one VC.

Such behaviour empowers, but massively increases, students’ expectations. They, not just universities, must take responsibility for the success of their studies and career.

With league tables taking the helm (especially in crucial overseas markets), undergraduates must step up to the plate and take advantage of the opportunities university presents to improve their prospects. Disengaged students and directionless graduates threaten a university’s league table position by poor degree results and not finding work.

The University of Manchester offered me much, especially as I only had a few lectures a week. But I shunned it all for lie-ins, daytime TV, and beer. I was the laddish student that William Richardson, general secretary of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference, recently criticised. Then, I graduated with a sense of entitlement that saw me only apply for jobs paying £20,000-plus.

Now, I take responsibility for my lazy university days, aimless 20s, lack of job satisfaction, and debt. The University of the West of Scotland’s talk of offering failing students tuition fee rebates and guaranteeing its graduates jobs is the result of competition. But this only tilts power further in favour of students and reduces their sense of responsibility.

From my experience, those who engage at university reap the rewards; student ambassadors, study abroad participants, and those who forge links with employers at university have all gone on to great things. Opportunities exist for all and achievements can now, thanks to universities, be documented and shown to employers in the form of a Higher Education Achievement Report.

Universities should not be held automatically accountable for a student’s failure, just because getting a degree costs a fortune and politicians have brainwashed a generation into a consumerist approach.

Shared responsibility is vital as students are vocal in questioning the worth of their study. Over half of respondents to a recent NUS survey thought their degree was not value for money. Yes, students can put in what they want as they are eventually footing the bill (hopefully, anyway, for taxpayers), but their university should not be damaged because of a lazy approach.

To restore this power balance and shift responsibility onto students, we need legally binding student charters with terms and conditions. Not the airy-fairy current ones. Charters would detail students’ responsibilities and their university’s expectations of them that must be met.

I propose potentially severe contractual punishments depending upon the offence; fines, marking down, suspensions, expulsions, and the withholding of degree certificates.

Students would be obliged to go to personal tutor meetings, mandatory careers advice, and lectures (with attendance counting towards a module’s mark). They would have to attend taster sessions on extra-curricular developmental opportunities like sports, societies, and study abroad. This differs to the current hands-off university approach but could improve a learner’s chances and address the perception that vital international students are not wanted.

Fostering this kind of engagement should improve university staff’s awareness of a student’s progress and any difficulties.

Such charters would offer students the best possible return on their investment, equipping them with the knowledge, experience, and qualifications to step out into the kind of meaningful future a university prospectus would proudly proclaim.

Twitter: @snoop2003 WordPress: JohnPaulWilson1

John Wilson is a university admissions officer and freelance journalist. He studied a BA in linguistics at The University of Manchester and a Masters in journalism at The University of Winchester.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments