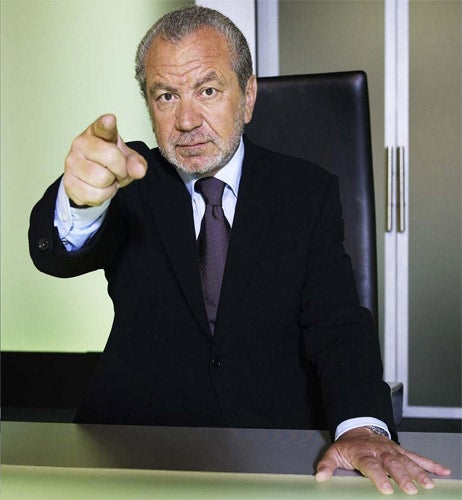

You're hired!: Apprenticeships are the best way to ensure fair access to the professional world

Apprenticeships have all but died out out over the past few decades but now they're coming back

A few decades ago, the concept of an apprenticeship was widespread in Britain, primarily as a way for young people from working-class backgrounds to learn the ropes and enter into a skilled blue-collar profession. In recent years, championed by the Government (and boosted by Lord Sugar's television programme of the name), "the apprentice" has been making a welcome return. For too long, they were largely absent from business and the professions.

In the case of the accounting profession, the model of the professional apprenticeship effectively disappeared by the beginning of the 1970s as growing numbers of young people chose to take degrees or go into further education, and graduates increasingly became the preferred recruiting targets of firms.

A rebalancing could be about to begin, prompted by the possibility that rising tuition fees may deter able school leavers from taking degrees and also by the desire of professional bodies and firms to identify ways of helping talent to develop, irrespective of background.

It is already harder now for young people from poorer backgrounds to enter the professions than it was 10 years ago. That is unfair. It is also an unhealthy place for any profession to find itself in. Why? The obvious point is that an enormous amount of talent is being ignored. The second point is that a failure to address the issue risks the development of an increasingly rarefied professional class.

Drawing a narrow group of people from narrow elites does not give any profession the best chance of engaging with and understanding those that it serves. A homogeneity of class, ethnicity, income group and education contributes to a particular mindset. This can be a strength as well as a weakness, but any organisation or profession is organic. It develops through new thought and fresh approaches. The innovation that can be achieved with different mindsets working together stands a better chance of becoming a reality with professionals from diverse backgrounds. There is also a competitive imperative. Strong professions are fundamental to economic development. Whether it's doctors and nurses ensuring a healthy workforce, or engineers creating modern infrastructure, national economies gain a competitive advantage from effective professions and they are a factor in influencing investment decisions.

Currently, the UK has such an advantage. But the world is changing. Many professionals come to the UK from countries where pay, conditions and opportunities for career development are poor. Economic growth in emerging economies will mean in the future that fewer professionals will leave those countries.

The flipside of this also applies. My own profession, accountancy, is increasingly influenced by global standards and rules. The skills of UK accountants are in high demand from other countries around the world, especially in the emerging economies. Other UK professionals are similarly sought after. Professions have always been about the importance of judgment rather than expediency. That must be preserved. If we do not have sufficient professional pathways for talented people in the UK, the risk must exist of bidding wars to shore up skills shortages. A professional class that becomes driven by financial incentive would not be worthy of the title.

To prevent these issues becoming a reality, entry to the professions must be as open as possible. That means firms such as my own changing the way we recruit, which is why we have announced a new scheme for school leavers whereby we will pay for students to take a university degree and obtain a professional accountancy qualification, while also paying them a salary.

I believe that increasing numbers of employers will start to find ways of contributing to the costs of higher education. GlaxoSmithKline, for example, recently announced that it would pay off the tuition-fee balance of graduates joining them. For companies to contribute to the cost of equipping young people with the skills they need makes good sense, and relieves the financial burden on both the individual and the state.

Employer involvement could also help to allay another fear that sometimes deters talented young people from less advantaged backgrounds from entering higher education: the worry that they will struggle to find a job at the end of it. The problem of graduate unemployment has been well documented in the press and doubtless makes some think twice. If you are potentially going to take on significant levels of debt, the knowledge that you should have paid employment on qualification is certainly a great reassurance.

It is a clear aim of the Government to increase and improve social mobility in this country. The Milburn report of 2009 laid bare just how much needed to be done in order to increase fair access to the professions. Now, I believe that we can begin to see real seeds of change, brought about in part by economic necessity. I have been encouraged, too, by the willingness of other institutions to work together in order to introduce this change. KPMG's school-leaver scheme requires the active participation of universities (Durham, Exeter and Birmingham) and professional bodies (the chartered accountancy institutes of England and Wales and of Scotland, the ICAEW and ICAS) – and all parties have been genuinely keen to get involved and work together to create new solutions.

Commitments such as these are just one example of how professions can begin to address the challenges of ensuring fair access. We want to broaden the circle of people who hear those wonderful words: "You're hired!"

Oliver Tant is UK Head of Audit for the accountancy firm KPMG

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks