What my first experience of NFL says about the future of the sport in the UK

Razzmatazz, political protests and infinitesimal detail: the NFL offers a whole different kind of sporting experience that, whether or not we want it to, is beginning to leave its mark in the UK

For the NFL newcomer, the first sharp intake of breath comes when you walk through the “tailgate”, the dedicated fan park where spectators gather before the game. On the face of things, it’s fairly standard fare: the usual rip-off food stalls, numerous bars serving the fizzy water Americans so generously describe as beer, a big screen showing the pre-game build-up, an interactive zone where you can throw footballs like a quarterback or test your sprint against an NFL wide receiver. But what really catches the eye is not the volume of the attractions, but the volume of the crowd. A check of the watch: 2pm. A full four hours before kick-off, the Twickenham tailgate is absolutely rammed.

People literally can’t get enough of NFL in this country, and in more ways than one. Nineteen of the 20 games to have taken place in this country have completely sold out. In the decade since the sport first arrived at Wembley Stadium in 2007, its London series has grown from one game a year to two, then three, and now four. Next year there will be four again, possibly more. The NFL claims to have three million “avid” (once-a-week) fans in this country, and yet during a quick stroll through the tailgate, I chatted to fans from Italy, Taiwan and of course the United States.

And yet, unless you are a dedicated follower of the sport, you could quite happily live in complete ignorance of all this. Sunday’s game between the Los Angeles Rams and the Arizona Cardinals attracted just 84 words in the following morning’s Daily Mail, 60 in the Metro, 20 in The Daily Telegraph, nothing at all in The Times, The Guardian or the Daily Star. A sporting phenomenon is gathering pace with frightening speed on our own turf, before our own eyes. Except that in large part, those eyes have been closed.

Including mine. Until Sunday, I had never been to watch a game of American football before. I arrived at Twickenham, the home of English rugby union, bearing a vague Anglocentric scepticism and the usual cliches: that for all its razzmatazz and undoubted popularity, American football was a faintly ridiculous made-for-television entertainment featuring large pieces of furniture running into each other at concussion-inducing volume. I departed not converted, exactly, but convinced. Convinced that I was witnessing not just an irresistible spectacle, but very possibly a model for the future of sport.

The second sharp intake of breath comes when the team rosters are handed out shortly before kick-off. These are the sheets of paper listing the players on both sides, and until you have seen them all written out longhand - hundreds of names scrawled over both sides of an A3 sheet - you cannot really conceive of the gargantuan, metropolitan vastness of an NFL team. There were, for example, six separate players called Williams. It was like being handed a phone book, or the menu at a mid-market Chinatown restaurant.

Such is the minute, infinitesimal mechanisation of this sport, one in which almost every single conceivable aspect of the game has been isolated, honed, and given to a dedicated specialist, often with his own specialist trainer. The tight ends have their own coach. So too the inside linebackers. The pass rush specialist. The strength assistant. The safeties coach. This is sport as mass production, Adam Smith’s pin factory made athletic reality.

For me, the man with by far the most interesting job in NFL is the long snapper. Sometimes a team will want to punt the ball: kick it as far up the field as possible to gain yardage. Sometimes it will attempt a field goal: a kick between the posts, worth three points. (These two jobs are performed by two different specialist players.) Naturally, you need someone who can feed the ball to the kicker as quickly and accurately as possible.

This is where the long snapper comes in. The long snapper’s job is to fling the ball through his legs to the kicker, and… well, that’s it. It’s not the most glamorous role, nor is it the most physically demanding. But as Jake McQuaide, the Rams long snapper, explains: “The job is simple, but not necessarily easy.”

At college, McQuaide dreamed of being a tight end, but quickly realised he would never be good enough to make it as a pro. So he decided to focus on long-snapping. “It’s a repeat-motion job, like a golf swing,” he explains. “If you do it enough, you can get pretty good at it. Anybody who can throw a ball overhand should be able to learn how to do it.

“If a punter’s right-footed, the perfect snap is into his right hip. On a field goal, directly over the spot, with the laces pointing down the field. The harder part is being able to block. That’s what separates the guys who can do it for a college team from the guys who can do it professionally.”

McQuaide is an engaging, enthusiastic interviewee, and there’s a reason for that: long snappers don’t tend to get many interview requests. At the Rams training base in Surrey earlier in the week, reporters clambered over each other to get close to running back Todd Gurley, or star quarterback Jared Goff. By contrast, I had McQuaide to myself.

“That’s one of the best things about it,” he argues. “I wish I were good enough to be a guy who plays a position. But it was a way for me to keep playing the game I love, and do it for a living. You get to be in the NFL, get a great job, and you get to go the supermarket or the beach, and nobody stops you. There’s only 32 of them, but it’s a pretty sweet gig!”

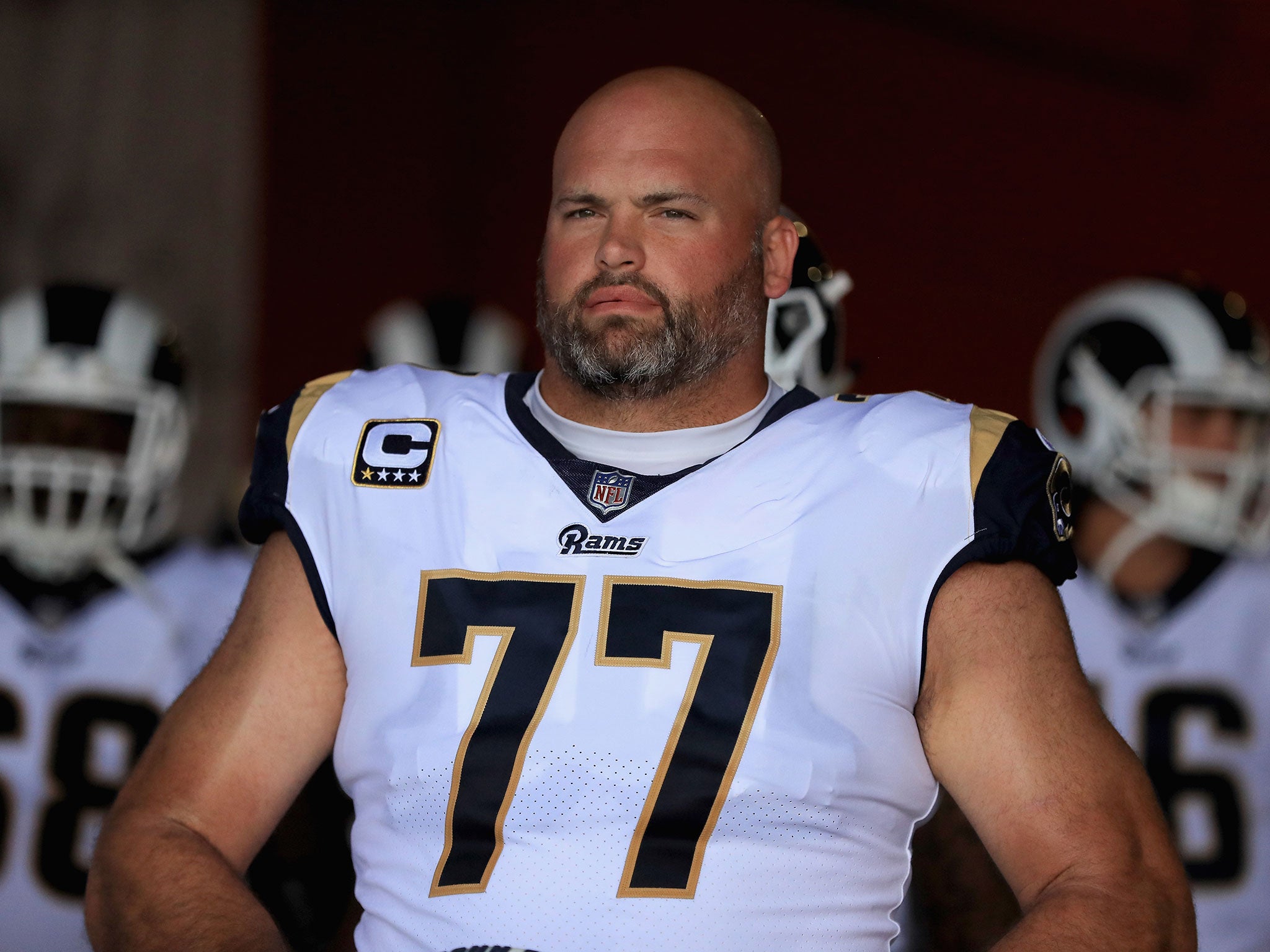

McQuaide’s tale is a reminder that this is a sport that really does take all sorts. Wide receiver Tavon Austin is a slight 5ft 8in and yet posted one of the fastest 40-metre sprint times in recent draft history. Andrew Whitworth, the heaviest player on the Rams roster, weighs in at just under 24 stone, and yet would still definitely beat you in a 100-metre race.

“I tell the young guys, my 100 per cent is probably 80 per cent, or 85, or 90,” he says. “Because I don’t have 100 any more.”

There is brain, of course, to go with the brawn. Virtually every NFL player has had a college education: McQuaide, for example, has a degree in aeronautical engineering. With a few notable exceptions, you don’t get really get to play this sport if you’re stupid. Before the start of the season, cornerback Dominique Hatfield tells me, every player gets handed the infamous “playbook”, the tactical dossier containing literally hundreds of intricate, finely choreographed routines, each one specifically calibrated to move the ball up the field a different way. You don’t get to keep the playbook. It’s too valuable for that. Players study it during training camp, memorise every play, and then give it back before the start of the season.

What if you forget a play?

“Then,” Hatfield says with a hollow laugh, “you get fired!”

For the first-timer, all this can make this an impossibly dense sport to navigate. Everything is a relentless assault on the senses, from the blizzard of meaningless statistics that pop up on the screen (“Arizona Cardinals 2-7 when playing on the East Coast at 1pm”) to the moment, right before the game, when all the players from both teams take the field, accompanied by enough soldiers to invade a small Latin American country. A reality TV star sings the Stars and Stripes. Robert Quinn, the Rams linebacker, is the only player still protesting the national anthem, raising a white-gloved fist in defiance.

Then all that gives way to pounding dance music, waving flags, an exceptionally excited announcer (“WHOSE HOUSE! RAMS’ HOUSE!”) and occasionally some legible football. It’s not a classic encounter. The Rams defence holds firm, carves out an early lead, and eventually they run out comfortable 33-0 winners. I take an instant liking to Gurley, the quicksilver running back who seems to run straight through tackles. I like the safety LaMarcus Joyner, who plucks an interception out of the air before being mobbed by jubilant team-mates all slapping him on the helmet, which is hardly going to help the NFL’s concussion problem.

To watch this spectacle is to glimpse a sport years ahead of many of its rivals in so many areas. The rulebook is extensive, byzantine and frequently highly pedantic (the one specifically outlawing “sexually suggestive” touchdown celebrations is probably my favourite), but largely unambiguous. Video technology is deployed in an enlightened, unintrusive manner. The referees issue their decisions not silently to players, but over the PA system to everyone. The NFL’s head of officiating will go on television to explain and defend the weekend’s decisions.

There is a refreshing lack of branding: the usual perimeter advertising screens and sponsored stadiums, of course, but the players and officials’ kits are almost entirely clean. There are still entrenched issues with concussion, with doping policy, with domestic violence, but the recent stand by players and owners against President Trump and police brutality has exposed a sport with a burgeoning social conscience that football or cricket could only dream of. If you could build a sport from scratch, it would probably end up looking a lot like the NFL.

Whitworth, who at 35 is not just the heaviest but the oldest player on the Rams roster, has been playing the game for more than two decades. What has been the biggest change? “The things they’ve done to take care of the guys from a health and safety aspect,” he says. “That’s going to be the thing that keeps this game successful. You’ve got to keep the guys healthy. You’ve got to have a bright future, something past football. As long as we continue to work on that, this game will continue to grow.”

In this country, at least, it will probably continue to grow regardless. There is talk of more games here, perhaps even a London franchise in the next few years. Amateur participation in this country has been growing around 15 per cent every year for a decade. Ten years ago, a kid from north London called Jermaine Eluemunor watched the first Wembley game on TV, decided to give the sport a try, and earlier this year was drafted by the Baltimore Ravens. NFL has already had an impact in this country. Now it is beginning to leave a legacy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks