‘Your identity disintegrates’: The mental strain of retirement and life after sport

Uncertain of what is to come, reflective over what has been and unsure of who they are as an individual, elite athletes can find it immensely difficult to adjust after stepping away from their sport, writes Samuel Lovett

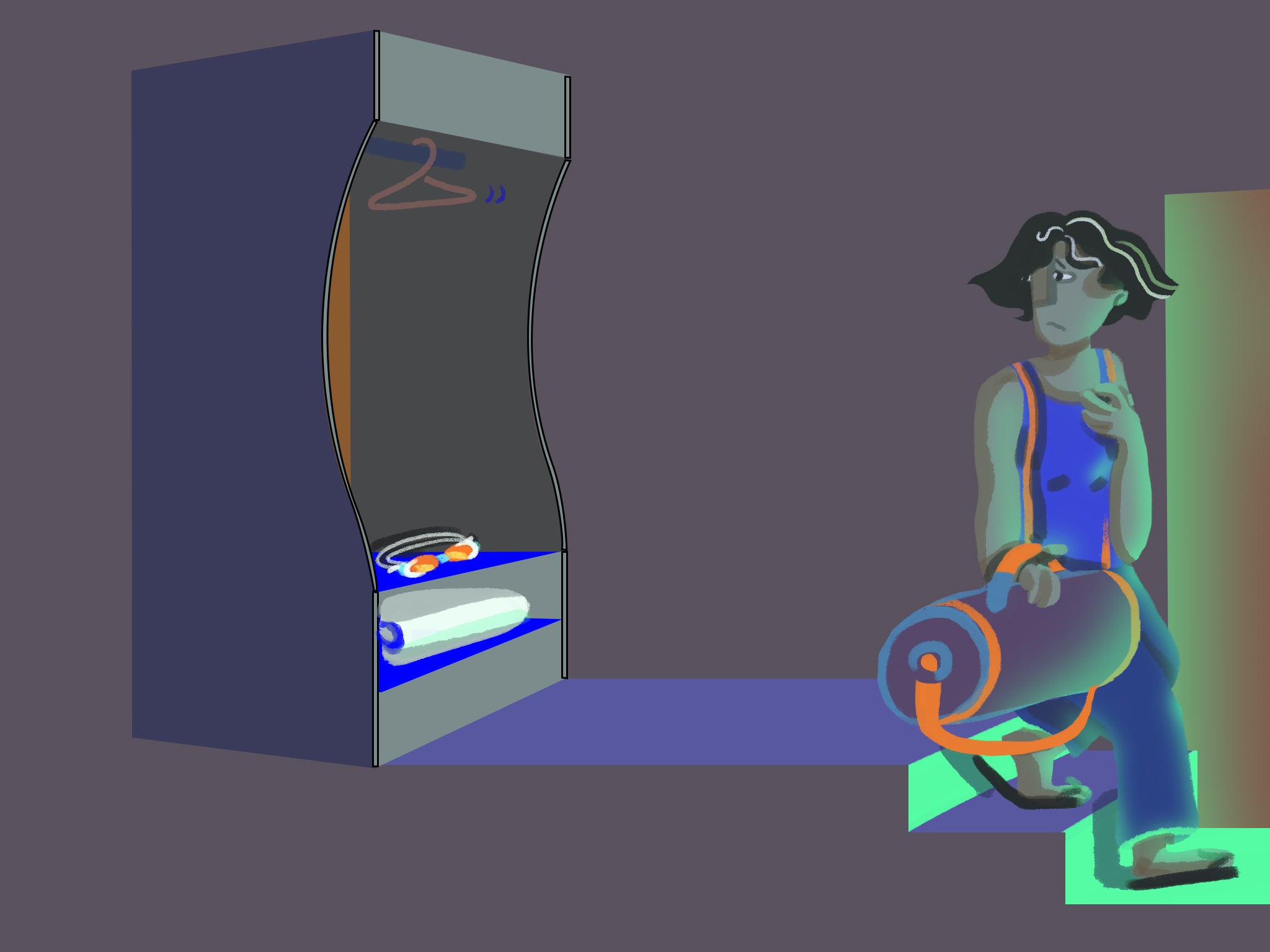

What happens when the spotlight dims? When the adulation and recognition fades, when the thrill of the game is gone, when the routine and familiarity of it all is lost. What then? What next? The transition out of sport can be a mentally arduous process for any athlete, raising doubts over self-worth and identity as the individual comes to grapple with their new reality.

Behind them, a life defined and shaped by the idiosyncrasies of sport. The highs, the lows, the fame, the fans, the sense of belonging, the sense of distinction, the pressure, passion and purpose.

Ahead of them, a life stripped of these qualities and experiences – their identity ‘guillotined’ before they can accept the reality of retirement. Uncertain of what is to come, reflective over what has been, these individuals can and do enter a space dominated by feelings of anxiety, depression and worse.

It’s an affliction that can strike down any sportsperson. From the one per cent who scaled unimaginable heights during their careers, affording them new opportunities after retirement, to those for whom professional sport lacked that polished and privileged touch – all are vulnerable in this time of transition.

Common sense tells us it’s this second group which would appear more susceptible. These are the footballers in the Women’s Super League who, on average, earn £26,752 per year. These are the rugby league players who, given the game’s demographics, statistically lack higher education. These are the tennis players ranked 100th in the world and beyond who are struggling to make a living.

Often, though, these individuals are already planning for life after retirement given their circumstances. Aware that their sporting lifestyle cannot last forever, and restricted by financial uncertainty, many know they can’t afford to live beyond their means and must be ready for what is to come. There is an impetus in these sports to prepare for the future.

“It’s something that is really important to do,” Ellie Simmonds tells The Independent. “It scares me some days. I want it to be a smooth transition to the next job. It’s a sport I’ve been doing all my life and I know it is going to end soon. I’m lucky I know what I want to do but the issue is how do I get there? I haven’t got a degree, I haven’t got anything like that. Once I retire, where’s my income going to come from? So it is a scary thought for sure.”

This forward-thinking is rare to come by in those hermetically-sealed sports where the focus is fixed firmly on success, where the money can be abundant and where every aspect of an athlete’s life, particularly in the upper echelons of that sport, is tended to by others. As a result, the shock of retirement can be seismic.

“I think it depends on the sport,” Gary Bloom, a leading sports psychotherapist, tells The Independent. “I see footballers with all their chips on one square, less so cricket and rugby because right from the get-go they’re encouraging their players to start thinking about the next step.”

But, in reality, sport, statistics and probabilities are all irrelevant. In that period of transition, every athlete can be at risk and every one of them must come to terms with leaving their old life behind, regardless of how long it takes.

The Independent knows of one former England international footballer who, having left the game more than 10 years ago, is still struggling with life after sport. Despite forging a successful career in the media and raising a happy family with his wife, this individual has yet to let go of his past.

In another case, a former academy player at a Premier League club attempted to take his own life after being mistreated by staff and later falling out of the professional game. He is currently receiving medical care but his experience, as with so many others, points to a parochial system that is still failing to take player wellbeing and duty of care as seriously as it should.

“This is just a personal view, and I hope I’m wrong, but if you think Gary Speed is going to be the last I disagree,” says Bloom. “I just hope to God I’m wrong. But we have to deal with this stuff. We have to look after our sportspeople. I had one ex-footballer crying on the phone to me recently. He was going to come see me but he didn’t and I’m worried.”

The manner in which an athlete leaves their sport can similarly shape their experiences in the years that follow. The turbulent nature of the transition can be heightened when forced to unexpectedly retire through injury. Equally, the failure to renew a contract – particularly at an early age – or the blow of being dropped from an elite programme, and having nowhere else to turn, can push many athletes over the edge.

Underpinning this sudden mental decline is the matter of identity, says Richard Thorpe, a therapist at Transition Consulting. It is the fuel to the fire.

“Identity is probably the primary issue in that transition out of sport – that’s the number one issue that other issues hang off,” he tells The Independent. “‘Who am I now? What is my self-worth?’ If you remove the sporting side, what is left? After spending so long identifying as a rugby player, footballer, cricketer, it’s like they’ve forgotten who they are as a person.”

Bloom goes further and suggests an athlete may feel like their identity has been “guillotined”. “Your identity becomes fused with that concept of yourself,” he says. “While you’re riding the crest of the wave that’s fantastic. But what happens when that stops? Then your identity disintegrates as it’s no longer wrapped up with being the thing that you’re best at.

“One of the footballers I’ve met, one of the things they hate most is being called an ‘ex-footballer’. It’s almost like an insult. Their identity is being guillotined and put aside.”

Then there’s the destructive self-criticism that comes with this unhealthy introspection. One of Thorpe’s clients, a famous former England cricketer, has fallen into this trap. Despite his success, this individual is plagued by thoughts of disappointment and underachievement.

“When you start to get into that head space, you start to ruminate, which is when your thoughts start to cycle in your mind and they spiral downwards,” explains Thorpe. “Rather than look favourably or positively over their career, they look at all the bad bits. ‘If only I didn’t get injured then, if only that coach didn’t come in, if only I did better in that game, I might still be playing.’”

This crisis in identity can equally spill over into an athlete’s relationships, culminating in more mental strain. “The issue with identity is that you attach your self-worth to it,” says Thorpe. “You believe the reason your friends are your friends is because you’re a pro rugby player; the reason your wife is married to you is because you’re a pro athlete. And that’s why divorce rates are very high, not necessarily because the women don’t like him anymore because he’s not a pro athlete; it’s the fact the athletes are struggling with their own identity and that creates stress in the relationship.”

Take into account the poor financial decisions an athlete can make over the course of their career, as well as the failure to properly prepare for the future, and it’s clear to see why those years in the immediate aftermath of retirement can prove to be so tumultuous.

The statistics confirm the issue at hand. According to the Professional Players’ Federation (PPF) 2018 survey, more than half of former professional sportspeople have had concerns about their mental or emotional wellbeing since retiring. In rugby union, it was revealed last year that: 52 per cent of professional players do not feel in control of their lives two years after they retired; almost 50 per cent had financial difficulty in the first five years; and 62 per cent of retired players have experienced some sort of mental health issue.

In football, research by XPro, a charity for ex-players, showed that three out of five Premier League players declare bankruptcy within five years of retirement. Thirty-three per cent end up divorced within one year of leaving the game.

Caught in this mental slide, athletes will often turn to vices – alcohol, drugs and gambling – to fill the void and reclaim the ‘buzz’ of their sporting career. “If you’re struggling with mental health, if you’re depressed, you’re always looking for a way to relieve the pain,” says Thorpe. “Alcohol tends to be one of the first [vices], or drugs because they give you an escape from this pain.”

Dame Kelly Holmes. Ollie Phillips. Andrew Flintoff. Mark Hunter. Frank Bruno. Catherine Spencer. Neil Lennon. Danielle Brown. Paul Gascoigne. Phelan Hill. The list of professional sportspeople to have suffered after retirement goes on. Some are instantly recognisable, most are not. But herein lies the point. Regardless of fame, riches and success – in whatever form they did or did not take – these figures found themselves helplessly drifting down a dark path after their careers had ended. All are vulnerable, all are susceptible. That this transition period continues to generate such pressing mental health issues demonstrates how far we still have to go.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks