It's the stroke of champions - so why is the single-handed backhand on the way out?

The explosive single-handed backhand is dying out in the modern, risk-averse game. But if today's young guns wish to elevate themselves to the heights of Sampras, Graf and Federer, says William Skidelsky, it's time to follow Stan Wawrinka's winning example and fire up the most thrilling shot in tennis

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At Wimbledon this year, one thing is certain: single-handed backhands won't be that easy to spot. There are some (very) high-profile exceptions: seven-times winner Roger Federer famously plays his backhand single-handed, as does his Swiss compatriot Stanislas Wawrinka (owner of probably the most lethal topspin backhand in tennis). At Roland Garros in Paris a few weeks ago, Wawrinka pulled off an unexpected triumph, beating world number one Novak Djokovic in the final of the French Open. Inevitably, his victory prompted questions about the single-hander's future: was this a glimpse of a possible resurgence for the one-handed backhand, the most glorious shot in tennis, or a mere death throe?

Wawrinka and Federer aren't alone in the men's game in pursuing this quaint and (many would say) outmoded shot. Elsewhere, there are ageing (and fading) exponents of the craft such as Richard Gasquet and Feliciano Lopez, as well as a clutch of youthful apprentices. But overall, double-handers significantly outnumber single-handers: at this year's Wimbledon, the figure will be roughly five to one. Meanwhile, among the women, sightings will be even rarer. Of the current WTA top 50, just two play their backhands unaided by a second hand.

Such scarcity is a shame, because, in contrast to all other strokes, it is virtually impossible for the single-handed backhand to look ungainly. Whenever it is unleashed, it's a free-flowing, pulse-raising delight. I vividly remember the down-the-line pass with which Federer saved a match point in his epic 2008 Wimbledon final against Rafael Nadal. The shot felt like a distillation not just of Federer's talents, but of all that is beautiful about the single-hander – with its exaggerated shoulder turn, coiling take-back, and sumptuous extension of the hitting arm. The single-hander, when struck well, is unique in giving the player access to blinding power with a seeming absence of effort.

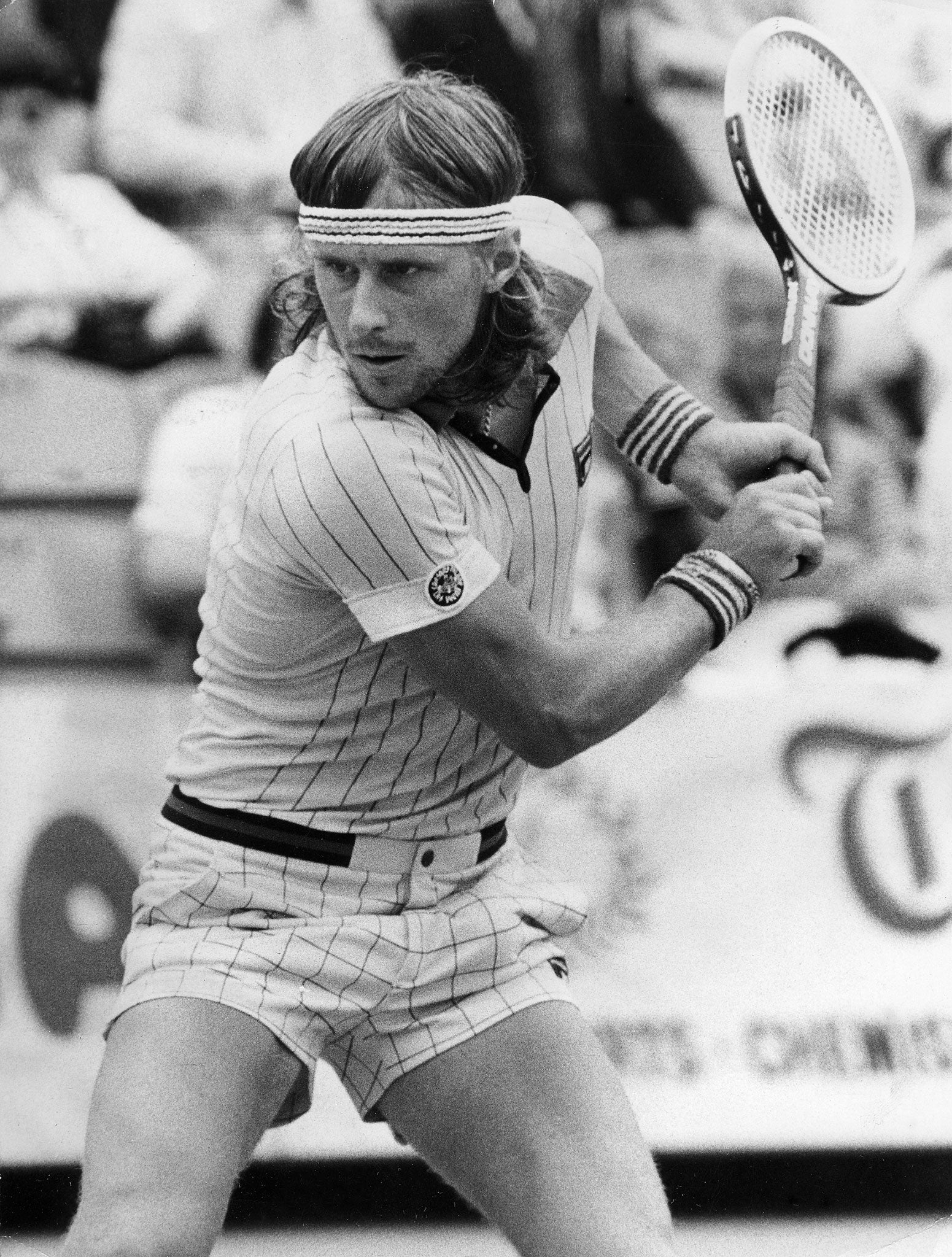

But tennis players aren't awarded points for aesthetic merit, and in recent decades the single-hander has suffered a dramatic downturn in fortunes. From being pretty much the only way to hit a backhand prior to 1970, the shot has gradually been eclipsed by the sturdier, more dependable double-hander. The shift began in the 1970s, when players such as Jimmy Connors, Björn Borg and Chris Evert popularised the two-fister. By the mid-1990s, single-handers were already a minority. In the ensuing two decades, the shot has fallen still further out of favour, to the point where some now prophesise its imminent extinction at the professional level.

What explains the decline? The standard view is that the double-hander's success reflects the fact that these days it's simply a more effective stroke. Over the past four decades, tennis has undergone numerous changes, and the sport's character has fundamentally altered.

First, rackets have been revolutionised: heavy, small-headed wooden frames have been replaced by lightweight, large-headed composite ones. As a result, players can swing faster and – crucially – load the ball with dramatically more topspin. Second, today's top players, like all elite athletes, are fitter and stronger (and taller) than their predecessors. Third, courts have slowed. Until the mid-1970s, three of the four Grand Slams were held on grass, tennis's fastest surface. Now only one (Wimbledon) is, and even the All-England grass is less lightning-quick than it was 15 years ago, when the authorities altered the seed mix to ensure that men's matches didn't descend into ace-hitting contests.

Although assessing the impact of these developments is far from easy, they have undeniably made the game more strategically defensive. Tennis today is much more baseline-oriented than it was. (Serve-and-volley, for instance, has all but vanished: remember the glory days of Stefan Edberg and his ilk?) As a consequence, consistency has become more valuable. Successful baseline play, for all that it may involve startling power, ultimately depends on the avoidance of error. The two-handed backhand may be a less destructive shot than the one-hander, but it is also more reliable: the extra hand on the racket means it is easier to handle incoming pace and spin, and to swing the racket along a predictable path. Crucially, too, players with double-handers are better equipped to deal with high-bouncing balls – which is especially important in the era of heavy topspin.

By contrast, the single-hander is a shot for gamblers and swashbucklers. The excitement of watching it stems not just from its inherent elegance but from the knowledge that the player is taking a risk. Unlike the two-hander, it demands – when hit with topspin – a full-blooded swing. There can be no half-measures: as soon as you start "pushing" at the ball, errors creep in. But the need for a full swing makes the shot inherently fragile. Get it the tiniest bit wrong, and you'll almost certainly miss. The upside of such riskiness is an increase in exhilaration. As someone who himself plays with a single-hander, I can say with certainty that there is no better feeling in tennis than using it to stroke the ball for a clean winner (not that, in my case, this happens often). For a tennis junkie, it's the ultimate high.

I suspect it's the single-hander's singularly dicey nature, rather than any inherent inferiority, that has relegated it to its current minority status. As elite sport has become more professional, the room for individual expression has diminished. Training a protégé is a massive investment, and coaches (and parents) want the surest route to future glory. Why saddle a youngster with a shot that may later prove a liability?

This logic particularly applies in the women's game, where single-handers are seen as especially vulnerable, given the strength required to play them (not that Justine Henin, possessor of one of the finest backhands in history, seemed to have much difficulty on this score).

So, along with the other changes to the game in recent decades, technique has become more uniform. David Foster Wallace noticed this in his superb 2006 essay "Federer as Religious Experience", in which he wrote of the modern power baseline game that, above all, it was "replicable: past a certain threshold of physical talent and training, the main requirements were athleticism, aggression, and superior strength and conditioning". He was exactly right. The dominant ethos of sport today is scientific rather than creative. Power has shifted from players to coaches: the holy grail is to find a reliable "method" for producing champions.

But this approach misses something, which is that, in tennis – as in all sports – the biggest prizes go to those who don't follow the conventional path. The rigid appliance of science may get you a very good player, but it won't very often result in a champion. The greatest players are usually innovators. This is true of Federer, and, in a less obvious way, of Nadal, who has taken the robotic imperatives of modern tennis to such demented extremes that, paradoxically, there is something revolutionary about him. It was true of Sampras and Agassi, of Graf and Seles, and of McEnroe, Lendl, Navratilova and Connors. All these players weren't merely good; they were different. They expanded the sport's possibilities.

And that's why the single-hander's future may well be less bleak than commonly supposed. For the game will continue to reward those who take risks. After all, even as the general popularity of the single-hander has declined, the shot has continued to hold its place at the apex of the game. The two dominant player of the 1990s, Pete Sampras and Steffi Graf, both had single-handers. In the Noughties, Federer won many more Grand Slams than anyone else, and Henin was one of the most successful women.

Just recently, it's true, the picture has looked different: only four major titles this decade have been won by men with single-handers, and there has been just a solitary victory for a single-handed woman (Francesca Schiavone at the 2010 French Open). But this doesn't mean that a future renaissance should be ruled out. In the run-up to this year's French Open, the consensus was that Djokovic's defensive, ultra-consistent game rendered him invincible. Yet Wawrinka beat him by overpowering him from both wings. His single-handed backhand was crucial to his hitting through Djokovic's defense. He won the title not in spite of, but because of, his backhand. Meanwhile, on the woman's side, Carla Suarez Navarro, possessor of a wonderful single-hander, has been enjoying her best ever season, breaking into the top 10.

So at this year's Wimbledon, lovers of the single-handed backhand don't need to look out just for Federer and Wawrinka, but also for Navarro and the Italian Roberta Vinci, not to mention Grigor Dimitrov and the talented young Austrian Dominic Thiem. And who knows? Maybe, in a fortnight, it will be a player employing this "throwback" of a shot who sinks to his or her knees in delight.

The Wimbledon Championships begin tomorrow. William Skidelsky is the author of 'Federer and Me: a Story of Obsession', published by Yellow Jersey Books, priced £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments