Stuart Lancaster resigns: A decent coach and man pays price for not being ruthless

One of England’s great developers of talent is probably now lost from the arena for all time

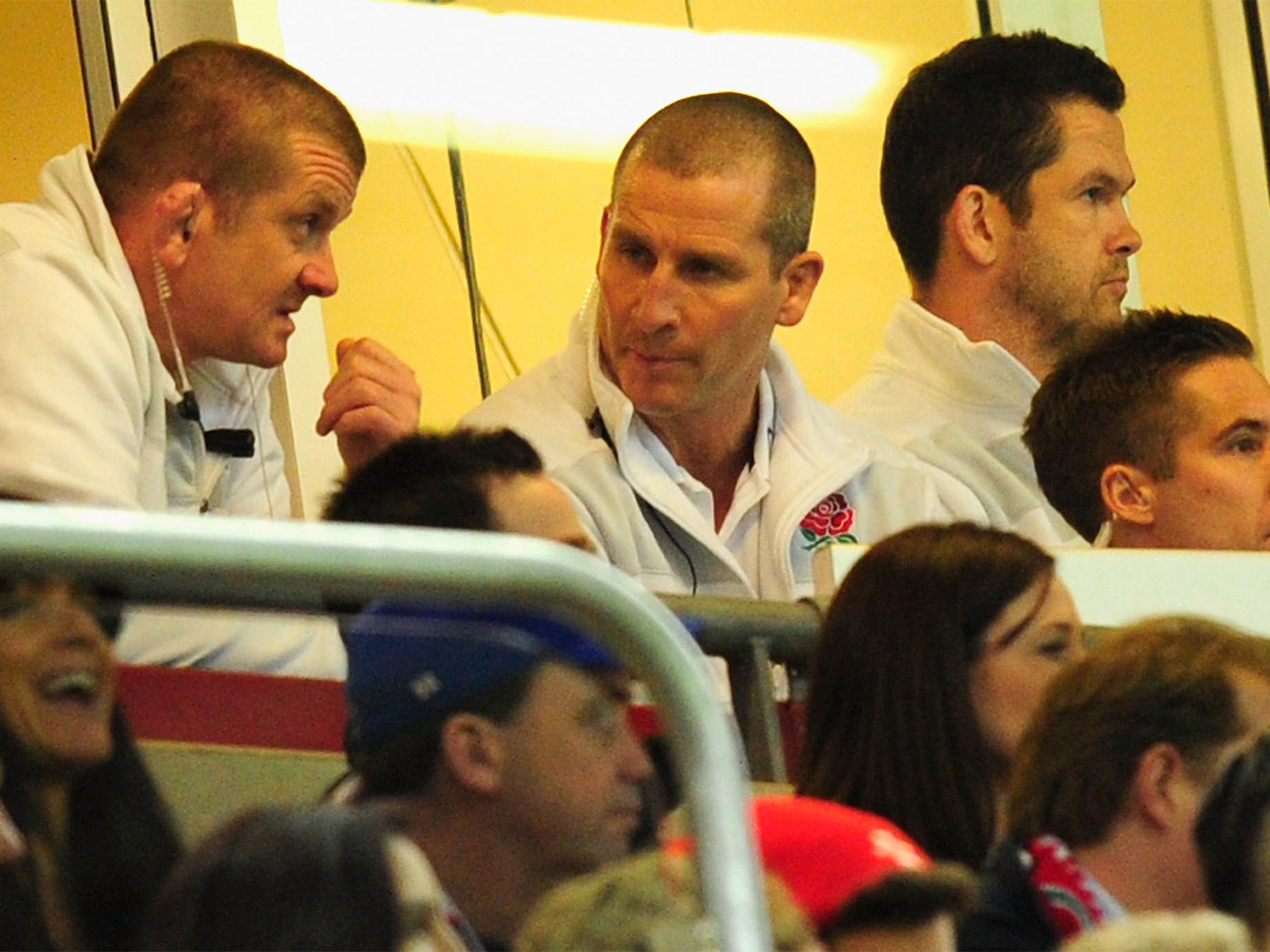

He seemed to know all along that it was over. That much was clear in some of the small details on that Saturday night in Manchester when Stuart Lancaster faced the ignominy of a dead rubber against Uruguay, the weakest team in the World Cup.

He appeared on the pitch as the England players warmed up that evening, reflective as he watched from beneath the posts. He had been at every press conference that week, ostensibly fronting up for his side’s failings yet also commanding the narrative while he could, before the last few dog days ran out on him. Lancaster had held far more of himself back before the disintegration of England, when we were left wanting more. The unturned empty pages of the black Collins A4 desk diary he always carried around with him – mid-term 2015-16: it would have seen him into the Six Nations – did not seem like an ironic commentary on this winter’s blank weeks, then.

The trouble with the arc of a story like Lancaster’s is that no one wants facts which deconstruct the received wisdom. No one will remember that Alastair Campbell’s Winners and How They Succeed cited him as one of the few who operate “outside of the comfort zone”, his appointment of Matt Parker from British Cycling an example of someone wanting to make his sport outward -looking. He has been branded the coach who drowned in management manuals, though there is infinitely more to him than that.

His relationship with those who write about his sport – much more honest than that of his predecessor Martin Johnson – was a metaphor for the way he got England back on track after the ignominy of the 2011 World Cup. You might want to demean his puritanical streak and sneer at the patriotism he wanted to inculcate, but it is easy to be wise after the event. English rugby needed putting back together again and he delivered in spades on that.

There was also the impact on the young players he gathered around him, which puts his successor in a very strong place for Japan four years from now. Some of them were in the midst of their A-levels when he took on the job and their ascendancy has not been a matter of luck: a golden generation plucked from a tree.

Ask his academy players at Leeds about Lancaster and they will tell you of an individual with a rare capacity for self-criticism, ready to search his soul for ways of being a better leader, motivator and communicator. Clear, unemotional, compassionate, hard-working, a delegator, possessing game intelligence: some of these qualities might seem mutually exclusive but they did not where he is concerned. To leaf back through the biographical details of those great days before the Twickenham storm gathered him up and spat him out was to grieve for the fact that one of this nation’s great developers of talent is probably now lost from the arena for all time.

When campaigns unfold in the manner England’s did, you usually see the real inside story from the battery of recriminations. There were very few this time. The tale of an unhappy Luther Burrell, whose associates revealed the tears he shed when omitted from the squad to make way for Sam Burgess, was significant. Very little more, though.

Lancaster was wise enough to know that World Cup cycles will make or break a soul and, for all that he might say to the contrary, he had contemplated what other horizons he would seek, if it all went wrong – and whether he would have continents to cross come winter. His self-analysis will, doubtless, give him cause to ruminate now on the fact that hard work and preparation and the cerebral can only take you so far.

The biography by the journalist Neil Squires, The House of Lancaster, which foretold with great accuracy the strengths and weakness which we know all about now, cited the testimony of Joe Bedford, signed by Lancaster when he got the first-team job at Leeds. Bedford adored the team’s organisation, the fact that “You’d never go into a game thinking: ‘where should I be?” But boy, Lancaster did love a meeting. “Yes, we did spend a lot of time in meetings.”

His England side felt submerged in analysis. There was a telling moment the morning after the Australia defeat when, by 10am, he had already attended a meeting of his management team and rewatched the game even before he sat down to talk about what had happened the day before. It was pointless. All hope had gone. Rigour can only take you so far.

Can he discover that accomplishments as a coach require more? It feels like a very long road back. A Sir Alex Ferguson or Steve Hansen would have taken the first flight to Toulon, sat down next to Steffon Armitage and told him that he – the best open-side flanker at his disposal – was going to be coming home to play for his country. Those men would also have had dismissed in cold blood those who were, frankly, not good enough: Chris Robshaw, Brad Barritt, Burgess. Ruthlessness in the white heat of international competition is innate. A meeting won’t make it. But the Lancaster story is a tragedy nonetheless. England needs its best coaches on the inside, developing the best players, not consigned to the plains of obscurity and a lifetime of regrets.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks