Meet Dave Ryding: Team GB’s world-class skier who learnt his trade on an indoor artificial ski slope in Lancashire

Exclusive interview: ‘Rocket Ryding’ is one of Britain’s best hopes for a medal in Pyeongchang at his third Winter Olympics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In total, Dave Ryding’s Olympics will last less than two minutes. In that time Ryding - Britain’s best alpine skier in a generation - will have twice plunged 572m down the Yongpyong Alpine slalom course, weaving his way in and out approximately 60 different gates which require constant changes of direction, and negotiating challenges ranging from strong winds to treacherous ice.

“A slalom run is about 55 seconds long on average,” Ryding explains, in our interview. “You’re hitting gates less than a second apart from each other. So to get an idea of what it’s like, just try jumping from side to side, once every second. It’s hectic when you get going.”

Hectic is something of an understatement. Ryding’s chosen discipline is one of the most technical in the entire Winter Olympics, a game of precision, daring and calculated risk, where skiers compete against the clock, and differences the width of a fingernail make all the difference between glory and disaster.

“To put it into perspective for you, our skis pass each gate by about a centimetre,” Ryding says. “There’s no margin for error. And then you throw in ice, rapidly changing weather, steep terrain. Basically, no other sport will ever compare to alpine skiing. Maybe motorcross or downhill mountain biking or something like that, but even then there’s still way more variables in skiing.”

The 32 year old, nicknamed ‘Rocket Ryding’, is one of Britain’s best hopes for a medal in PyeongChang, his third Olympics, after establishing himself in the top ten on the elite World Cup circuit in the past couple of years.

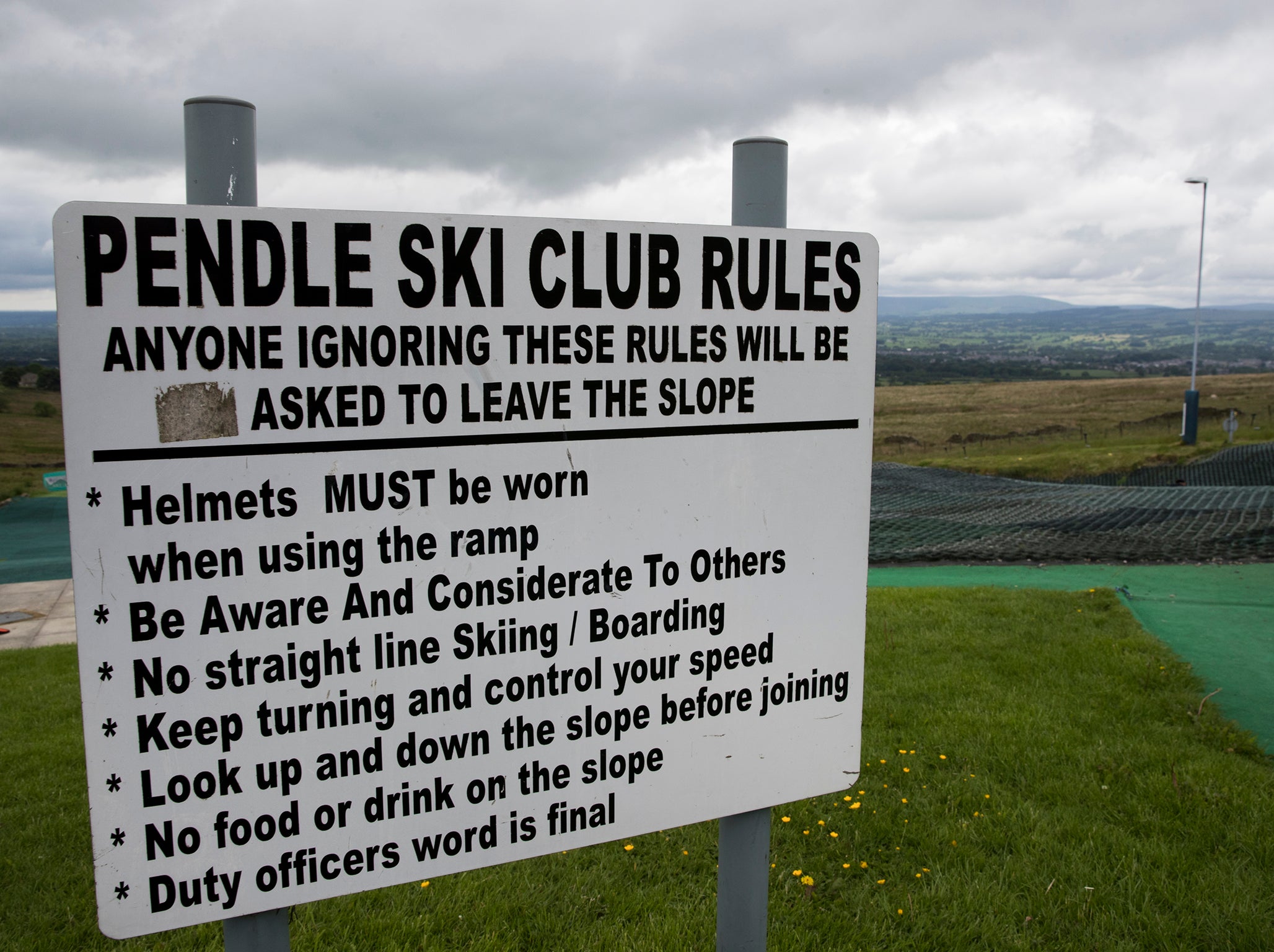

But Ryding’s ability to mix it with the best in the world from Austria, France, Switzerland, skiers who were born and bred on alpine snow, is all the more remarkable when you consider that he learnt his trade, not in the mountains, but on indoor artificial ski slope in Pendle, a picturesque town in Lancashire. And at 20, an age when most young prospects are already touring the European circuits, Ryding was still training in the English countryside, with his sole experience of snow coming on a family skiing holiday when he was 16.

"Compared to the rest of the top guys at the Olympics, I’m pretty unique as the only skier who wasn’t brought up on snow," Ryding says. "No one else started on a dry slope and skied there until they were 20.”

Ryding admits his fledgling ski career would have died before it even began if it hadn’t been for his dad Carl, a self-taught skier who coached his son and gave up his job selling women’s lingerie at a market to retrain as an engineer so he could fund Ryding’s early forays onto the Europa Cup circuit, the lower echelons of international skiing.

“It’s a bit like the lower levels of the professional tennis tour when you start off,” Ryding says. “There’s a few spectators, little prize money and the competition’s intensely tough. I was lucky as my family sacrificed a lot to allow me to ski full time, and a couple of local companies and my ski club took a chance on me and said they’d like to try and support my bid to make it onto the World Cup circuit.”

However, money was tight and for almost a decade Ryding lived out of a suitcase, travelling Europe and preparing his own equipment, something almost unheard of for an international skier. “For years it was just a coach and myself going around, living out of each other’s pockets for 300 days of the year which also puts a strain on things. And every day I’d have to spend 2 hours doing my own skis, prepping for the next day, whereas the people I was racing against didn’t have to worry about any of that stuff as they all had servicemen doing their skis for them.”

So rare are elite British international skiers, that Ryding found himself an object of curiosity at most races. “After Alain Baxter (the Scottish skier who won bronze at the 2002 Olympics before having the medal taken away for failing a drugs test), we had a period where there was no one doing anything so a lot of European skiers don’t expect to get beaten by a Brit,” he says.

One of Ryding’s favourite stories, illustrating the contempt with which British skiers were regarded, was when Rainer Schonfelder, an Austrian veteran who won the 2004 World Cup slalom circuit decided to quit skiing for good after being beaten by Ryding at a race in 2012. “It was a pretty small race back then, and after I made the podium at the World Cup event in Kitzbuhel last year, Schonfelder actually came up to my coach and said, ‘Now look at Dave! Maybe I shouldn’t have stopped.’”

But by 2014, Ryding was close to the end of the road. He’d competed in two Olympics, but at 29, years of grind had worn him down. “As a kid my dream was always to be ranked in the top 30 on the World Cup circuit,” he says. “That was my big goal. I won the Europa Cup in the 2013 season, but still didn’t get any support from UK Sport. And then a year later, I finished 31st in the World Cup standings, still preparing my own skis. I’d missed the top 30 by one point and I was devastated. So I was thinking, ‘Can I really do this? I’ve tried everything. I’m 28 years old.’”

After a week of heart-to-heart conversations with his family and coach, Ryding opted to give it one more shot. And then came the phone call he’d long been waiting for. “I’d had a few top thirty finishes and some people at the federation took note and decided to support me and provide my own serviceman. I guess I’ve proved it was worth their investment.”

After coming second in Kitzbuhel last year, the first British skier to make a World Cup podium since 1981, Ryding has consolidated his rise with five top ten finishes this season. But he still isn’t satisfied. “I’m a bit frustrated as I don’t think I’ve shown exactly what I’ve got on race day,” he says.

“There’s a lot of tactics in skiing. Last year I was just trying to ski and do my own thing. This year I took the decision to try and mix it with the best, and I’m taking a few more risks which haven’t always paid off. I was leading the first race of the season after the first run, and then was still leading when I crashed halfway down the second run. And then two races later I was actually winning the race at the very last split, made a mistake in the last 7 seconds and finished sixth. So things are there, but I’ve just not quite done it. Hopefully I can save those two perfect runs for the Olympics.”

Ryding knows that getting into the medals in PyeongChang will come down to the very finest of margins, and no little luck on his side. “They create a different course for the first and second runs, and you get thirty minutes to inspect it and decide where you think you can risk. Sometimes you get tricky terrain or difficult gates in different places on the piste so it’s not always easy to get it right the first time. All you can do is push out that gate, go with 100% intensity and trust in yourself.”

But whatever happens, Ryding’s unlikely rise has earnt the respect of the alpine skiing world, with even the legendary Marcel Hirscher paying tribute to his ability. “Marcel’s a great skier but a good guy too,” Ryding says. “His dad used to coach at a dry ski slope in Holland so he understands where I come from and what I've had to do to get here. He’s quite a gentleman, always been very complimentary to me.”

Back in 2002, a 15 year old Ryding watched in awe as Baxter briefly claimed his unlikely Olympic bronze. 16 years later, a repeat of the feat would cap the remarkable rise of a man who has made it to the top in his own unique way.

“I remember Alain getting his medal and seeing him get four World Cup top ten finishes,” Ryding says. “At the time it was only watching him that made me think this crazy dream could actually become a reality. I’ve gone on to have nine top ten finishes and a World Cup podium, but I’m still criticising myself all the time. I believe I can do more, it’s just a case of doing it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments