The science of sprinting

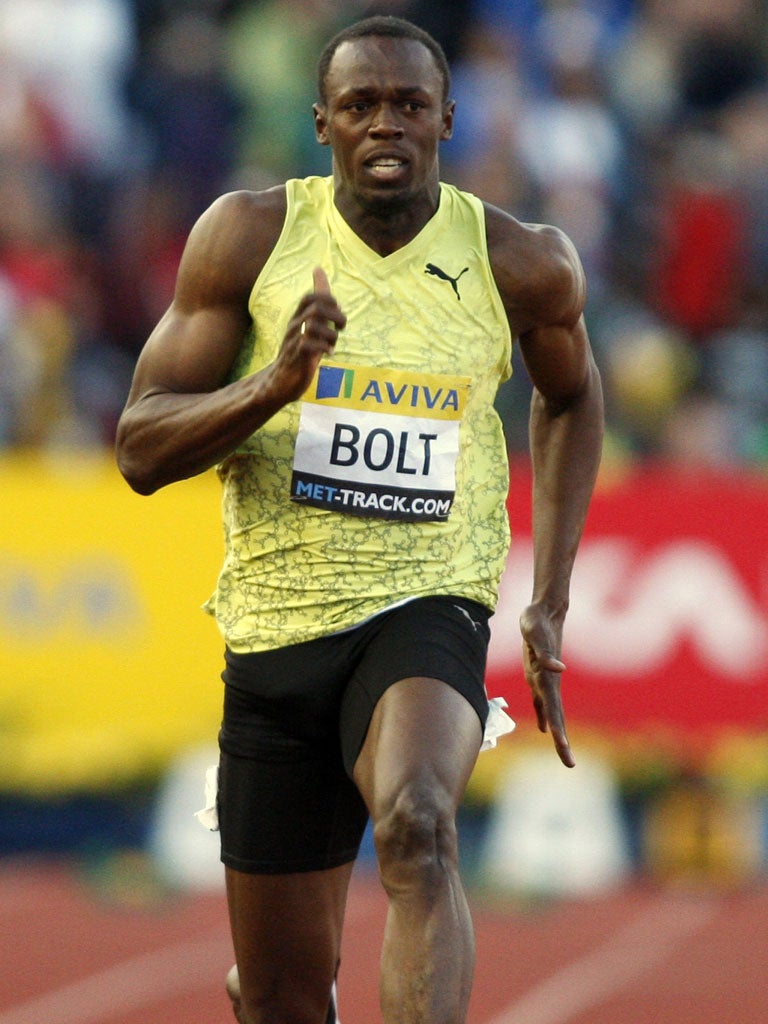

What is it about Usain Bolt – who begins the defence of his Olympic title today – that gives him an edge over his stockier, more powerful rivals? Steve Connor investigates

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Usain Bolt, the fastest man on earth, takes to the starting blocks for the 100 metres race tomorrow night people may wonder whether there will ever be a more perfect sprinter.

Body shape, muscle strength, the relative lengths of legs, heels and toes, as well as a fine-tuned nervous system to pull the whole thing together, are just some of the biological attributes that make a world-class runner.

At 6ft 5in, Bolt is taller and leaner than most top sprinters but still conforms closely to the scientific predictions for what enables someone to run breathtakingly fast over short distances – in his case a record 9.58 seconds for the 100 metres.

The American sprinter Carl Lewis, a former Olympic champion who holds nine gold medals, is three inches shorter than Bolt yet was almost a stone heavier than the Jamaican athlete when Lewis held the 100 metres world record in the 1980s.

Alan Nevill of the University of Wolverhampton believes that Bolt epitomises the changing shape of world-class sprinters who are getting more "linear" – taller and leaner than their shorter, more muscle-bound predecessors.

"The body shape of male sprinters seems to have changed over the past decade or so. Taller, more linear individuals are emerging as the better sprinters and we think it's got something to do with increased stride length," Dr Nevill said.

Sprinters with longer legs have longer strides – an advantage in the middle stages of the race when they have reached their top speed, which they must maintain until the finish line.

Shorter, more powerful legs are better in the earlier, acceleration stage, but Bolt can evidently compensate for his slight disadvantage over his shorter, heavier competitors.

Sprinting is an extreme form of running requiring a combination of physical and mental attributes that can be honed by intensive training. Yet most experts would agree that a world-class sprinter is born rather than made.

In Bolt's case, it helps that he is from Jamaica. Studies have shown that black athletes with West African ancestry have significantly more "fast-twitch" muscle fibres, which tire easily but contract more quickly than the "slow-twitch" fibres commonly found in long-distance runners.

"To be a great sprinter you need leg muscles that are dominated by fast-twitch muscle fibres because they shorten the muscle quickly and generate power," said Professor Steve Harridge of Kings College London.

"Marathon runners have more slow-twitch fibres, which is one of the reasons why you are never going to turn Paula Radcliffe into a great sprinter, or Usain Bolt into a good long-distance runner," Professor Harridge said.

Weight training can make fast-twitch fibres thicker and stronger but there is no evidence to suggest that it is possible to convert one type of muscle fibre to another by training alone.

Scientists have also found that there are certain natural variants of a gene called ACTN3 that can boost the performance of fast-twitch muscle fibres. Again, whether you have the "sprint gene" or not depends on whether you have inherited it. Some nationalities, such as Jamaicans, are known to have a higher prevalence of the sprint gene than other groups.

Genes are also involved in determining the length of a person's Achilles tendon and toes. Good sprinters have shorter tendons than expected for their height, and their toes are proportionately longer. This allows their calve muscles to do more work in the acceleration phase of the sprint.

But training is also important in bringing out the best in what a sprinter such as Bolt has inherited. It can make muscles stronger, but also improves their ability to store energy in the form of creatine phosphate, a substance that allows them to produce short, powerful bursts of muscle activity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments