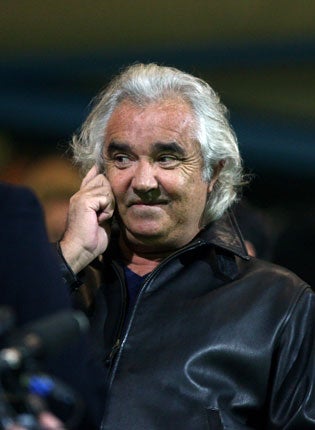

Flavio Briatore: The ego who landed... with a crash

Poll of the Decade: In the first of our series of features revealing the results of our online survey into the good guys, wrongdoers and key moments of the past 10 years, Flavio Briatore is named villain of the decade

Flavio Briatore, the son of two primary school teachers from northern Italy, started out as a ski instructor in the Maritime Alps, which exposed him to the rarefied air of the wealthy elite. It would also provide excellent training for the slippery slopes he would negotiate so adroitly until 16 September 2009, when his Formula One team announced that: "The ING Renault F1 Team... wishes to state that its managing director, Flavio Briatore, and its executive director of engineering, Pat Symonds, have left the team."

Despite protestations of innocence – and an appeal – from Briatore over Crashgate – at the 2008 Singapore Grand Prix an FIA inquiry found he ordered Renault's Nelson Piquet Jnr to crash deliberately in order to hand team-mate Fernando Alonso an advantage – those 26 terse words brought his colourful career to a clinical, but necessary, end.

Five days later, the FIA announced its verdict: "For an unlimited period, the FIA does not intend to sanction any international event... involving Mr Briatore... or grant any licence to any team or other entity engaging Mr Briatore in any capacity whatsoever. It also instructs all officials present at FIA-sanctioned events not to permit Mr Briatore access to any areas under the FIA's jurisdiction."

Ever since Briatore's arrival in Formula One in 1989 as a self-confessed motor racing ignoramus, the one-time insurance salesman played fast and loose with the tenets of competitive sport. The Crashgate scandal that blew up this year sealed his fate and also ensured Briatore topped The Independent's poll as sports villain of the decade. As one voter wrote, "Any man who can make Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley look saintly has to be the villain of the decade."

Controversy marked Briatore's early years with the Benetton team, particularly during the 1994 season when they were frequently under suspicion or investigation by the FIA.

The reintroduction that season of refuelling stops provided Briatore with an opportunity to cut corners in the chase for points. At the German Grand Prix, Jos Verstappen's car caught fire during refuelling, injuring the Dutch driver and four pit crew. The subsequent investigation found that the team had removed a fuel filter in order to allow quicker refuelling, but because of a disagreement over whether this had been authorised by an FIA official, Benetton escaped punishment.

Such an incident eerily foreshadowed the events 14 years later when Piquet Jnr crashed at Marina Bay. Briatore's escape from punishment in 1994 confirmed the Italian's belief in his own infallibility; the sport's governing body created an ego that cannot be dismissed as a mere pantomime act.

Despite a movement towards greater driver safety and improved car reliability in the early 1990s, Briatore was rarely afraid to let his true feelings be known. Wearing his ignorance of the sport's finer points like a badge of honour, he proclaimed: "All the team owners are orientated towards the technical side rather than the entertainment side, and this is a big fault."

Briatore's psychology allowed no room for growth or redemption but how did a man with so little regard for motor sport come to lead Renault and Benetton to seven world championship titles and hire two of Formula One's biggest stars, Michael Schumacher and Alonso? His move from the ski slopes to the city brought him into contact with businessman Attilio Dutto. In the wake of Dutto's Paramatti company going bankrupt, Briatore was convicted of fraud and sentenced to four and half years in prison. True to character, his story now becomes as murky as the machinations of an FIA investigation. To avoid prison, he fled to the Virgin Islands before returning to Italy in the mid-Seventies following a legal amnesty.

While working in Milan prior to his prosecution, Briatore continued to make influential friends. It was here he met the fashion entrepreneur Luciano Benetton. When Benetton opened a series of US franchises in 1979, he chose the 29-year-old Briatore to head the operation. A key part of the brand's success – and the original source of Briatore's wealth – was its controversial advertising campaigns. Briatore's attitude to them reveals the psyche he brought to bear on the sport over the last decade.

"We decided to do something very controversial that people would pick up on – 50 per cent of people thought it was great and 50 per cent thought it was awful, but in the meantime everyone was talking about Benetton," said Briatore of billboards that featured horses mating and collages of genitals.

His rise to Formula One's highest echelons owes much to a combination of bravado and opportunism. When Luciano Benetton appointed Briatore as commercial director of his Formula One team in 1989, the influential team owner asked a certain Bernie Ecclestone to look out for him. Eighteen years later, the two men, Ecclestone and Briatore, would take over at Queen's Park Rangers, where Briatore has already seen eight managers come and go in his role as club chairman.

Following his FIA ban, the Football League launched an investigation to decide whether Briatore still passed its "fit and proper person" requirement. The Football League board discussed the matter on 8 October and declared that it would be awaiting responses from Briatore to certain questions before commenting further.

Briatore surrounded himself with brilliant people but, as the respected engineer Symonds' role in Piquet Jnr's crash proves, the force of his power can make villains out of even quiet men. Any villain must either redeem himself or suffer for his villainy. After Alonso and Piquet Jnr qualified down in 15th and 16th respectively for the Singapore Grand Prix last year, Piquet's leaked testimony stated he had met with Briatore and Symonds to discuss engineering a crash.

The result of all the scheming was the team's first victory since Alonso himself had taken the chequered flag at Suzuka 33 races before.

The leaked transcripts from the team radios were illuminating. Drivers typically rely on the pit-lane board to keep them up to date with what lap they are on, but in the build-up to his premeditated crash, Piquet Jnr is repeatedly heard asking, "What lap are we in, what lap are we in?"

The strong finish to the season saw Alonso and, more surprisingly, Piquet Jnr remain at the team for 2009. However, Briatore's sacking of the Brazilian after the Hungarian Grand Prix in July, following 10 scoreless races in a row, would set in motion his own demise. After Piquet Jnr went public with his version of events, Briatore had a final shot at redemption. Instead, his last act of villainy was to accuse Piquet Jnr and his father, the former world champion Nelson Snr, of false allegations and blackmail.

Once removed from Renault, Briatore continued to deny any wrongdoing. "I was just trying to save the team," he said. "It's my duty."

Villains of 2009: How the other contenders fared

With twice as many votes as his nearest rival, Flavio Briatore's status as the sporting villain of the decade is assured but how did the other contenders fare? The freshness of Tiger Woods' fornications saw him pull in 13 per cent of the vote but come the Masters in April, sports fans everywhere – and the golfers who rely on him for increased prize money and sponsorship – will surely forgive all in the hope of witnessing his unique Augusta mastery once again.

With his orchestration of 'Bloodgate', Dean Richards, the disgraced former Harlequins coach, matched Briatore's supposed planning ability. That he polled just six per cent of the vote suggests an acknowledgement that Tom Williams and his botched bite of a blood capsule created no chance of endangering lives, although beneath that farce lay serious issues regarding sporting morality and abuses of power.

The presence of four cavalier businessmen on the list tells you all you need to know about how the sporting landscape has changed since the turn of the century. There is no more memorable depiction of the last decade's wanton lust for money than Sir Allen Stanford landing his monogrammed helicopter on the Lord's outfield. After showing off his chopper, Stanford and cricket legends Sirs Ian Botham and Viv Richards were photographed in front of a giant Perspex box stuffed full of filthy lucre – pornography for the Noughties.

Leeds United may be riding high at the top of League One but the mention of Peter Ridsdale's name still provokes a response in nine per cent of voters; not surprising given that tales of his contractual generosity have already entered football folklore. The last businessman on the list made it his business to corrupt athletes by peddling the steroid THG. For that act of villainy, Victor Conte polled 11 per cent, which also applies to the BALCO athletes: Marion Jones, Tim Montgomery and Dwain Chambers.

Conte exploited athletes looking for the competitive edge, unlike the late South African cricket captain Hansie Cronje who sold his side's competitive spirit to Indian bookmakers. Like Conte, he polled 11 per cent of the vote, but they both finished behind runner-up Thierry Henry, who picked up 15 per cent of the vote. The Barcelona striker earned infamy – and France a place at the World Cup – through an instinctive wave of the hand, but at least he didn't risk anyone's life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks