Brooks Koepka: Golf's world number one who always came second

Seizing long sought-after recognition as golf's best player might act as a catharsis for Koepka

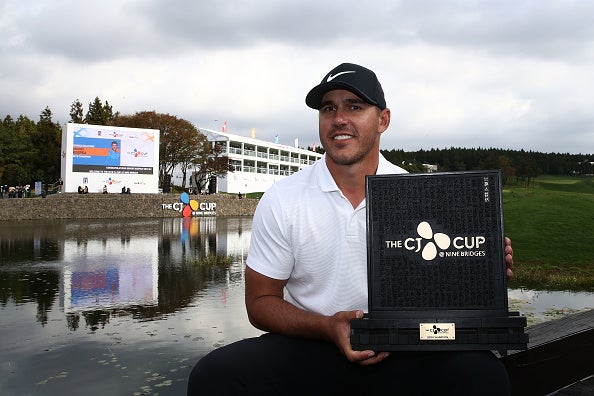

Entering the final day at the CJ Championship with a four-shot lead, only the most foolhardy fan would have questioned golf’s indomitable closer, Brooks Koepka.

One glance at the game over the last 18 months tells you that when the brawny Floridian takes stranglehold, there’s not a bullpen from Major League Baseball to South Korea’s KBO League capable of impeding the great-nephew of legendary shortstop Dick Groat.

So a win amongst South Korea’s pine-strewn paradise, colloquially known as the Taj Mahal of golf, and Koekpa’s long overdue promotion to officially being crowned golf’s premier world wonder seemed a formality.

Yet still, the manner of his victory, an eagle on the par-5 finale to secure the perfect strikeout and hold off Gary Woodland’s late charge, was tailored to Koepka like a mitt to his fingers. A man embittered, almost phobic, of finishing second in anything or to anyone.

But that determination doesn’t stem from transcending societal restriction and circumstance, as is the way with many great sportsmen and women. No, in fact Koepka was a hard-jawed and handsome teenager who attended a private high school in Palm Beach and his drive is fostered by a belief that he is persistently underappreciated, which has equally deep roots in his character. The underdog mentality is spurred by a lifetime of second-place finishes.

Even golf itself was a reluctant second for Koepka - a jet-setting burden forced upon him after being stripped of a baseball career when involved in a grim car crash aged ten which, according to his father, “left him looking like he had done six rounds with Muhammad Ali”.

As a teen Koepka lagged behind the country’s best junior talents. He was rejected by his favoured university, failed to win a tournament in his first three years at college and was better known for his protein-powered temper tantrums. He was overlooked for a position on the Walker Cup team and failed to qualify for a place on the PGA Tour.

While Jordan Spieth emerged as Tiger Woods’ sweet-cheeked successor, Koepka ostracised himself from American golf and joined Europe's lower-rung Challenge Tour, trekking the continent, sleeping in cars and sharing hotel rooms while wondering if the first-tee announcer would again add an unwanted extra syllable to the pronunciation of his surname.

When he won his first tournament in Spain, just a few weeks after joining the circuit, Koepka left the trophy behind in his hotel room. It was plastic, worth little more than a bowl of paella, and he considered it unworthy even as a keepsake.

But when more victories soon followed and Koepka was crowned the European Tour’s Rookie of the Year, he expected to arrive on the PGA Tour as the subject of at least a little transatlantic fanfare. Instead, as he held aloft his maiden trophy of true silverware on the tour, he was eclipsed by Spieth’s two majors. And even now he finds himself playing second fiddle to better-known stars like his friend, Dustin Johnson. Jilting memories as fans waltzed straight by him in a Jupiter gym last year to get Johnson’s autograph, ignoring the Floridian as though he were nothing more than his best buddy’s bodybuilding coach rather than a man with twice as many majors.

Another slow needle inserted during acupuncture. Another compass point to reinforce the orientation - the overlooked, the underappreciated, the outsider, the rejected - which makes Koepka such a cold and lethal player.

Still to this day Koepka thinks “golf is kind of boring”. That he is certainly not one of those scrawny “golf nerds”. He is a baseball man, bloodline to a precocious home-run hitter, a golfing stranger by definition of his machismo.

Koepka’s celebrated coach, Butch Harmon, caustically calls his star pupil the most underrated three-time major champion in history. But Koepka often seems to contrive that identity himself; the mental silhouette who ignores him, who enrages him, who trifles at the deprivations which boil his blood and pump through his biceps, without which victory can’t follow.

Take when he declined to go on the US Open champion’s customary press tour, saying it wasn’t really his kind of thing, before lashing out when the media didn’t ask him for an interview just over a year later.

“[The media] has their guys they wanna talk to,” Koepka said. “I’m not one of them and that’s fine. I don’t need to kiss anyone’s butt….Come Sunday, I won’t forget it when everyone wants to talk to me because I just won. I don’t forget things.”

Koepka might always have to feel second to be first. And that very trait may always leave him second in the eye of the public too. The less than a little endearing traits - impassive and monosyllabic - which allow him to be such a ruthless and unremitting performer. Maybe finally seizing the belated recognition of being the world’s best player can act as a type of catharsis for Koepka.

More likely though, it is a two-fingered salute. A South Floridian spit at all those fans who left the green to follow Tiger before he finished putting, the captains who left him out of the President’s and Walker Cup teams, and even the car which denied him the career in baseball chasing his great-uncle’s insuperable legacy. To them, Koepka can now raise two-fingers because he is indisputably the middle one, the number one.

“He knows how to put that little chip on his shoulder,” Bob Koepka said after his son became the first man to defend the US Open for almost three decades this year. The real question is whether Koepka can ever take it off?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks