Racing: Echoes of Red Rum as Ginger hits the front approaching the last

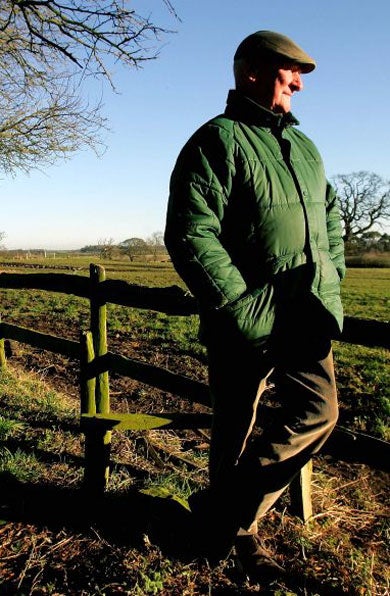

Ginger McCain, as famous for his eccentricities as for his triumphs at Aintree, is readying his runners for a final tilt at national glory

Ginger McCain has such a tireless instinct for self-parody that it seems difficult to know how to react when he suddenly has to be taken so seriously. As the trainer of Red Rum, after all, his name is synonymous with one of the most quixotic sporting adventures of the last century. And McCain always embraced his role with the same disdain for precedent as the horse himself.

By the time he won his third Grand National, the whole country knew that Red Rum was stabled in a cobbled yard behind a car showroom in Southport, and that he was trained on the beach by a former taxi driver. This McCain character had once chauffeured a lion to London, and taken Frank Sinatra around Southport in search of a hairbrush. "An insignificant little man," McCain remembered. "I always thought Bing Crosby was better."

Between them, horse and trainer made it hard to know where reality ended, and caricature began, and that certainly seemed to suit Ginger. As a result, however, McCain became victim of a different, more corrosive orthodoxy. There was a common suspicion that Red Rum was a freak who had stumbled into unique, capricious harmony with his oddball trainer.

In truth, McCain did not always discourage that assumption. As the years went on, the animals he ran at Aintree seemed steadily less deserving, while his opinions grew steadily more provocative.

All of a sudden, however, McCain is commanding fresh deference from a sport that has tended to treat him like a cherished but batty old uncle. Two years ago, he became the first trainer to win the National for a fourth time, with Amberleigh House. This is a man who took 12 years to win a selling plate - the worst type of race there is - and who would typically have no more than two dozen horses in his care at any time.

And now, in his final season before handing over to his son, Donald, he has somehow come up with another perfectly credible contender for the great race. With an impudence that might have been borrowed from his trainer, Ebony Light thrashed one of the Cheltenham Gold Cup favourites, Kingscliff, at Haydock last month. He had been dismissed at 33-1, but jumped and galloped so eagerly that he had the race wrapped up with half a mile to run.

Ebony Light, moreover, is merely icing on the cake. With 26 winners on the board, and more than two months still to go, McCain has already passed the best score he ever managed back in the Seventies. Fifteen years ago McCain left Southport to rent stables in the manicured parkland of Cholmondeley Castle, in Cheshire, and it finally seems as though his horses are going upmarket, too.

Typically, he manages to find cause for exasperation in the yard's success. He sits on his sofa, a big, cursing, florid man surrounded by dozing dogs, and fulminates over the declining standards of stablework. "The horses are running out of their skins and I don't know why," he said. "I go to the racecourse and they have got coats on them like seals, bloody beautiful coats, and I can't accept it, I can't believe it, because they're not being done as they should be done. The truth of it must be that the others are being done bloody terrible."

Donald, as mild and reflective as his father is cheerfully intemperate, smiles indulgently. He does not particularly mind what the horses or their stalls look like, so long as they are fit and healthy enough to win races. Whatever else he may be, McCain is a man of generous spirit and happily gives his son much credit for what has been happening. Donald in turn attributes it to an extension to their all-weather gallop. One way or another, the horses are undeniably flourishing. "It's not because they are very good," McCain said. "It's because they are very fit and they are seeing their races out."

McCain has a restless sense of mischief. On the other hand, when he is being outrageous it tends to be because he is outraged. There is no mistaking his authentic vexation with a changing world, where he is expected to respect health and safety officers, the rights of foxes and, even - Gawd help us - women. Suddenly they are everywhere. They have broken out of the kitchen and even get in his way on the racecourse, where they serve as stewards, judges, starters.

"Woman starter? Like that silly cow with the hat and the skirt," he said. It is not clear what she is supposed to wear instead. "People like that poncing around. How can men have any respect for things like that? There are women I respect. I can't think of any, apart from the Queen, but there must be."

He can go on like this for hours, and some people react like a cat meeting a bulldog, arching their backs and hissing. But it is far more sensible to sit back and enjoy the show. His execrations move on to the timidity of modern life. The previous week he had twice been obliged to take a horse home when racing was abandoned, first because of a fire in a garden shed adjacent to Ayr racecourse, and then because the track doctors had been needed to escort a young jockey to hospital from Uttoxeter.

"All right, it's sad the boy got kicked," McCain said. "He's got a broken nose, cracked a cheekbone, perhaps. But you can swallow a lot of blood before it kills you. In the old days, jockeys were expendable. We didn't call off meetings if one got hurt, we wrapped them up, slung them in the ditch, and buried them if they started to smell."

The public at large is apparently no less effete. "All these safety precautions on racecourses - railed off here, railed off there, in case somebody gets kicked," he said. "Bloody hell, let a few of them get kicked, they'd keep out of the way then. It's gone right over the top, it has."

Beryl, his wife, has mended one of his dentures with superglue. Sometimes she must wish that she had applied it to his lips instead, as when a throwaway remark about the competence of women riders before the National last year caused nearly as much rumpus as the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand. McCain in turn records that his friend, Harvey Smith, advised him to get rid of Beryl because she is too old to breed, and too savage to keep as a pet.

But she is never more fierce than in protecting her husband, with his heedless relish for being misunderstood. She winces at every breezy reference to the ignorance or sexual orientation of those he encounters on the racecourse. "Nice little man," he said of one. "But he's starting to have opinions, and he's being robbed blind, too."

He yearns for the days when half the world map was coloured red, when cavalry officers brought their habits of discipline and decision-making to the racecourse, when the Waterloo Cup drew bigger crowds to the North-west than even the National. Now coursing has been banned, and Aintree itself might not have survived without Red Rum.

"What can you respect these days?" he asked. "You're not allowed to believe in yourself, in your country, anything." But then, surprisingly, he shows that he does not expect to turn back the tide. "That's part and parcel of life," he shrugged. "Things go like that, from the Romans onward."

His consolation is that so long as anyone has any interest in the National, his name will endure. What he can never understand is why it seemed to be forgotten during the years after Red Rum. The old horse helped to keep him afloat in retirement, but McCain was in serious difficulty by the time he left Southport.

"We always knew we were capable of doing it, if we had the right horse," he said. "A lot of people thought I was a one-horse trainer. I couldn't give a toss. If I only had one horse, didn't I make a good job of it? Truly it didn't bother me. But when we won the fourth National, where in the old days we'd all have been whooping, it was pure satisfaction."

If anything, McCain feels that adversity made him a better trainer. "They say good horses make good trainers, and they do to a point," he said. "But anybody can train good horses. You've got to struggle through all your bad-legged horses, your moderate horses. Winning a seller with a cripple - that's very satisfying. I have never been jealous of anybody: not for their women, or their money. But I have envied people nice horses."

In his autobiography, McCain wrote that he had failed to match other trainers in the gentle art of "kissing bottoms and bullshitting". He confessed: "I don't think I have ever been considered a really good trainer within the racing world."

He has already redeemed that perception, with Amberleigh House, and perhaps Ebony Light could yet make his last laugh the loudest of all. Yes, Red Rum was a freak, but McCain believes the horse could never have achieved as much elsewhere. In his boyhood, he saw how the old horses pulling shrimpers' carts in the bay renewed their crippled limbs in the salt water. "In a normal, run-of-the-mill training centre, Red Rum would never have lasted," he said. "I needed him, but he needed Ginger McCain, and he needed Southport."

Red to Amber: The life and times of Ginger McCain

* PROFILE Born 21 September 1930. Married in 1961 to Beryl. Two children, Joanne and Donald. Took out a permit in 1952 to train his own horses behind the garage of his motor trade business premises at Southport. Became a public trainer in 1969. Moved to Bankhouse Stables, Cholmondeley, near Malpas, Cheshire, in 1990.

* BIG RACE WINNERS Aintree Grand National four times: Red Rum (1973, 1974 and 1977) and Amberleigh House (2004); Scottish Grand National: Red Rum (1974).

* BEST HORSES TRAINED Amberleigh House, Glenkiln, Honeygrove Banker, Hotplate, Imperial Black, Kumbi, Red Rum, Sure Metal.

* FIRST WINNER Trained for 12 years before sending out his first winner - San Lorenzo in a selling chase at Aintree on 2 January 1965.

* FINAL GRAND NATIONAL RUNNERS Ebony Light, 33-1 winner of last month's Peter Marsh Chase at Haydock, is set to join Amberleigh House as McCain's last runners in the Grand National on 8 April.

* GINGER ON AINTREE "You can have your Gold Cup days at Ascot with all those formal, up-nosed people, and you can have your Cheltenham with all your county types and the tweeds and whatever, this is a people's place and a people's race."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks