Whiff! Whaff! The beautiful game may be coming home

Ping-pong tables are about to spring up all over London. Howard Jacobson celebrates an overdue sporting and social revolution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Boris Johnson made a good joke in Beijing a couple of years ago when taking over custody of the Olympics, reminding the Chinese that table tennis, originally called whiff-whaff, was ours before it was theirs.

"The French looked at a dining table and saw an opportunity to have dinner," he said. "We looked at a dining table and saw an opportunity to play whiff-whaff." In fact table tennis was also called gossima in the early days, and, given that Gossamer is the brand name of a condom, the Mayor of London missed out on an even better joke, perhaps calculating that the Chinese wouldn't get it.

The upshot of it, anyway, is that in the run-up to the Olympics Boris Johnson is making good on his promise and "bringing whiff-whaff home". One hundred table tennis tables are about to be positioned around the capital, in squares, railways stations, shopping centres etc; thousands of bats and balls will be provided, any number of related talks, lectures, quizzes, and even singalongs will take place, and, assuming all goes to plan, a great wave of ping-pong enthusiasm – Ping! the campaign is called – will break on London.

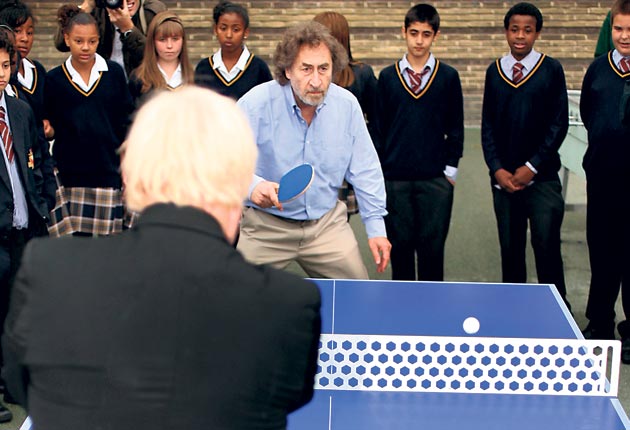

I pinged it with the Mayor the other day in the playground of the Burlington Danes Academy, where he was opening a schools table-tennis tournament, whipping the young players up into a ping-pong patriotism they could only partially share – "Can we beat the French?" "Yes!" "Can we beat the Chinese?" "No!" But I at least beat him, 11-5, 11-4, though talking to the Chinese television cameras afterwards he insisted it was 11-5 on both occasions. I told him that if every point mattered to him so much he should at least have undone the middle button of his jacket. He accused me of competitiveness. It was like having Ronaldo point the finger at you for diving. The Chinese television reporter wasn't wildly interested; she wanted to know whether the Mayor really believed that by putting tables all over London he could mount a serious challenge to Chinese ping-pong ascendancy by the time of the 2012 Olympics. "Of course not," Boris laughed – this was about fun not winning.

Our match was not a classic. Neither of us was in what you could call scintillating form, but he pushed the ball back low and deep and with enough backspin to keep me watchful. The crowd of school kids clapped enthusiastically, not so much amazed by how well the Mayor played as amazed he could play at all. I thought he had it in him to be a player: he enjoyed being at the table, commanded his space, had a good eye and quick reflexes, and glared ferociously between points, but probably lacked the necessary application. In the end it was my forehand smash that made the difference. In my youth I was known as the "Prestwich Hitter" – a description that read better than it sounded – and to be hitting again was proof that for me at least the Mayor's initiative was already working.

Even before the tables have gone up I know I'll be sorry when they are taken down. I want them to stay forever. In the parks and public spaces of the once great table tennis playing nations of Eastern Europe, and of course in China where the game now thrives, concrete tables are a common sight. We never had such amenities in this country, but it was always easy to get a game because every church hall and boys' club and workers' canteen had a table. Wherever there was a social club there was a table-tennis team. I was mad on the game in the 1950s as was every one I knew. I am still accosted in the street by people I don't recognise who remember the margin by which one of us beat the other in the Manchester and District League in 1956. If they tell me they beat me I dispute it.

Then came the passivities of television, and after that computers, and that was the end not just of table tennis but the social clubs in which we'd played it. Social? What's social? Can you get an app for that?

There are other reasons why the game's popularity faded. It became a sport. The charm of table tennis had always been that everyone believed they could play it. The first world table-tennis champion won his title Boris-like, in an unbuttoned cardigan. This was what pleased my mother about my playing it. Not too much running around in the cold. And that little ball couldn't do anyone any harm. In truth I dislocated my opponent's knee during the first competitive match I played, teasing him with a drop shot of such sweet perfection that he came charging in to collect it and collided with the table, but I didn't dare tell my mother that. I left her with the illusion that I was playing a game my granny could safely play.

I'd learnt it on the kitchen table – Boris's mention of a dining table gives away his upper class antecedents – using a cork bat and not worrying if the ball had a dent in it, and that sense of its being a family game never fully faded. Which might also explain why my school never honoured me at morning assembly, no matter that I was picking up cups and medals all over the county. To the school, I might just as well have been captain of the Lancashire Junior Patience team. Then the Japanese invented the sponge bat and suddenly the ball was travelling at the speed of light and you had to be an athlete to retrieve it. Almost at a stroke, table tennis went from being a parlour game to a test of the highest sporting prowess.

Many of us still mourn the passing of the earlier version, played with ponderously slow pimpled bats, and requiring of the players a sort of philosophical detachment, as though there was all the time in the world to win a point, and the musical to and fro of the ball was its own hypnotic pleasure.

Part of the reason so many great players came from what was left of the Austro-Hungarian empire was that table tennis suited their amused and introspective lugubriousness. It was more psychology than sport. We felt one another out, grew to know one another's idiosyncracies, enjoying the witty dialogue of the game, the ping to the pong, the sudden accelerations, the subtle variations of none too violent spin.

The new technology, first of sponge, then of sandwich, then of glue – for you strip your bat down now and reglue it to make it faster or slower, more sticky or more slippy, depending on what you know of who you're about to play – changed all that forever. Table tennis became more furious, less dialogic, more contemptuous. The sponge bats deadened sound. The first time I played against sponge it was like being ambushed by an invisible opponent. You couldn't hear his bat on the ball, and because its surface had a mind of its own you couldn't read what kind of stroke he'd played. Fear entered the game. A new unfriendliness. It was as though you didn't exist. You were simply someone the ball had to be driven past at uncanny speed. Eventually, the fun went out of it.

Unless, of course, you were of the new breed of player and loved the power the sponge bat gave you. Two shots were all it was meant to take now to win a point. You sent down a neurasthenic serve that had 15 different sorts of spin on it, including no spin at all, and if the guy at the other end managed a return, it was invariably high enough for you to murder. The great Chinese players of today achieve this – the three-ball kill – with both their feet off the ground, like predatory birds in flight. It's a spectacular sight, and if you have two players of equal power and athleticism pitted against each other, the contest can be breathtaking. But it's for connoisseurs. You have to know what it is you're watching. Put Federer up against Nadal and you don't need to have played much tennis yourself to appreciate what they're dishing out. With table tennis players of equivalent stature you do. And that's why we don't know their names. They are specialists of genius but their specialism leaves us cold. They are gladiators of the abstruse.

In China, where it doesn't look at all abstruse, their great players are houeshold names and whole districts will turn out to watch them play. That was once the case with table tennis in this country. Thousands packed the Albert Hall or Wembley to see the Hungarian Victor Barna try to backhand flick his way past the impregnable defence of the Austrian (but naturalised British) Richard Bergmann. They were both my heroes – the problem was deciding, in the course of a game, which one of them I wanted to be. Barna's flick was a sublime arch of the arm and turn of the wrist, as sudden as a snake bite, but ah! Bergmann was dancing so far back from the table he could have been playing someone else, picking the ball up from his toes and returning it low and dipping over the net. Photographs show the massed spectators engrossed in this contest, wearing the trilbies of film noir existentialists and smoking like the chimneys of Brno. Those were the days – when the final of a major table tennis championship could be played in a fug of tobacco!

But did whiff-whaff ever really go away? There remains, in hotels, holiday camps and schools, a remnant of the old table tennis which anyone can play. Burlington Danes Academy reports a resurgence of interest in the game. It is reputed to be hip, suddenly, in New York, and there are definite signs of its returning to sophisticated dining tables over here. Perhaps Ping! is all that's needed to have it up and running – slowly – again. If Boris Johnson succeeds in bringing back some of the game's old pleasures then players and non-players alike should be delighted. Just don't expect us to be ready to take on China at the 2012 Olympics.

Howard Jacobson's table tennis novel, 'The Mighty Walzer', is published by Vintage

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments