James Lawton: Calzaghe summons spirit and will to join boxing's pantheon

In some areas Hopkins was undoubtedly the more assured performer

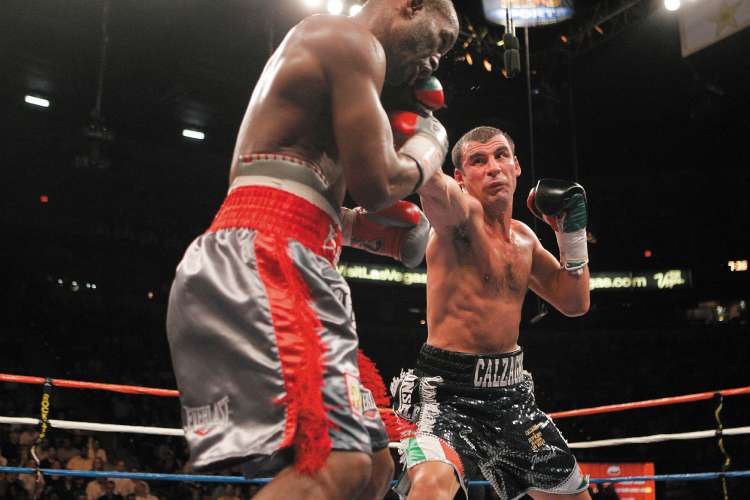

Joe Calzaghe left his most dazzling skills, and so much of his intimidating swagger, back home in his Welsh valley but he brought here to Las Vegas for examination the one asset that Bernard Hopkins couldn't touch and maybe couldn't even understand.

He came with a heart that proved itself beyond any kind of intimidation or cunning. It was one that in 18 years of undefeated fighting, and 11 years as a reigning world champion, had never served Calzaghe better than in the small hours of yesterday morning when he was knocked down early in the first round by a short, sweet right hand. The blow carried the shocking impact of imminent disaster.

Never before had a fighter performing on American soil for the first time, and with anything like such a reputation to protect, been placed under such harsh and instant pressure.

Two points down after the first round, and another when Hopkins was so much quicker to the punch and so much more acute and adroit in the close places in the second round, Calzaghe had to do more than fight back. He had to remake himself.

Eventually he did so, not in his entirety, not with the freedom that had carried him to so many of the 44 victories on his unblemished professional record, and not in some eyes even to an indisputable win, but in a way that said, yes, this is a serious fighter, one who cannot be shaken easily or cynically from his purpose even in the most unpromising circumstances.

In this we had irrefutable evidence of a spirit and a will to be placed at the highest levels of British boxing history.

It wasn't just the knockdown that disoriented Calzaghe and separated him for much of the fight from the best of his self-belief. This was especially so when it came to the old confidence that an opponent could be swept away with his trademarked device of throwing too many punches, too quickly, from too many angles and just too irresistibly to permit anything more than passing defiance.

There was also the disturbing onslaught of evidence that Hopkins might indeed know too many of boxing's darkest arts and still, at the age of 43, retain the technical skill and just enough energy to prosecute them with destructive effect.

That threat might well have been enforced by a man some years younger who had, along with superior ringcraft, a spirit to match that of Calzaghe.

But where Calzaghe had a heart, one that carried him through the bleakest place a fighter can ever know, Hopkins had a set of calculations.

In the end they failed because they were too much concerned with stealing an advantage, sneaking an edge, while all the time Calzaghe went forward, scattering the demons that had gathered so quickly around his bruised head, and forcing the action in the only way he knew. It was by fighting from that place we have probably mentioned too much but which cannot be avoided because it was utterly central to the story of Calzaghe's rescued dream of, as he put at the end, "not just coming to America to fight but to win".

That the victory should be accompanied by The Ring magazine world light heavyweight title was an incidental bonus. Calzaghe was not here to pick up another bauble to go along with the world super-middleweight title, but to vindicate all the glory he had achieved without ever stepping into what will probably always be regarded as the true testing ground of the American ring.

When the split decision came in Calzaghe's favour Hopkins was outraged. He claimed that he had just taken his opponent "to school" and taught him some basic lessons of boxing and if anyone doubted this they should look at the video because the reason video evidence sent so many people to prison was that it just doesn't lie.

There was an element of truth in this, because in some areas Hopkins was undoubtedly the more assured and accomplished performer, and on one official scorecard and many others around ringside he did indeed conjure the verdict. It was also true that the winning margin of 116 to 111 awarded by the judge Chuck Giampa (Ted Gimza made it 115-112 Calzaghe, Adelaide Byrd, 114-113 Hopkins) was a gross exaggeration of the superiority Calzaghe was able finally to establish.

Some of this was conceded by Calzaghe. He admitted that the early knockdown made him wary of Hopkins' right hand and inhibited his normal range of punching, making him come in a little square and less poised for damaging work. "I knew it was pretty close at the end but I thought I deserved to win," he said. "I know I didn't box as well as I might have done but it's very difficult to look good against someone like Hopkins. He wants to spoil from the word go and as the fight went on I felt I was fighting a bit square, I wanted to straighten my punches. But around the seventh round I knew he was fading. He was struggling to breathe and then, of course, he started to play for time."

Most outrageously, he stretched out the time the referee Joe Cortez allowed him for recovery from a low blow in the 10th round and there were two other such efforts to stop the clock and the pressure it was applying to his dwindling stamina. If this was the school to which Calzaghe was being taken, we could see now it was one which taught winning not as the natural consequence of heightened will and courage but something to reward trickery, if not outright sharp practice. This, along with the ability of Hopkins' legs to support a strategy of clinching, stifling and sneak attack, was always going to be the key issue.

Naturally, the Hopkins camp put it rather differently. His trainer, Freddy Roach, bemoaned the failure of the judges to note the difference between the volume of Calzaghe punches and those that landed cleanly. "Judges are human beings, I know" said Roach, "but it is very disappointing when they do not seem to recognise what is going on there in the ring. They rewarded Joe for aggression, maybe, but how accurate was that aggression? He threw a lot of punches but not many landed – you can see that just by looking at Bernard's face."

Hopkins couldn't summon even a fleeting moment of grace in defeat, or even resignation. "Yes, look at my face," he said. "My nose isn't at where my ear is. I wasn't hardly hit. I was beaten tonight but it wasn't by Joe Calzaghe."

In fact he was beaten by a combination of forces. One was Calzaghe's growing sense that the crisis had passed, that Hopkins had done his best work and was finding it increasingly difficult to repeat. The other was the fifth column of the American's own crucial weakness, his failure to protect that huge early advantage because he simply didn't have enough strength. The clinching became more persistent and if Hopkins could still throw an occasionally jarring right, notably in that extended 10th round, he couldn't regain any of that early authority.

By the end Calzaghe had won back much of his own. Welcomed into the ring by a contingent of compatriots fired by Sir Tom Jones' passionate rendering of the Welsh national anthem, he stumbled and fell under the first clinical force of Hopkins. But he came again in the way of fighters whose first instinct is to fight rather than perform sleight of hand and head and shoulder. It was a philosophical difference which in the later rounds, except for the 10th, had become a gulf, and this was the triumph of Calzaghe.

Whether it justified the claim of his promoter, Frank Warren, that he had made himself the greatest British boxer to come to this foreign shore was no doubt something that invited a longer view and a more forensic debate, but in the meantime it was no hardship celebrating a night when a demonstrably honest fighter had found salvation, by however narrow a margin.

Calzaghe was asked how he now ranked in the pantheon of his nation's sport. Was he at the top of the list? "That's not for me to say," said Calzaghe. "All I know is that I came here to win, and I did that. It was very important to me, and, I think, the way people will look at my career."

Hopkins, for all his passing reputation and some notable scalps which include those of Felix Trinidad and Oscar de la Hoya, two of the most talented fighters of their generation, probably has a less secure legacy. He will, surely, be remembered as the fighter who tried always to find new ways to win, ways that were less about what he did but what he prevented the others from doing.

What he couldn't stop Joe Calzaghe doing was fighting his own fight and going his own way. That was the true nature of the triumph at the Thomas and Mack Center on 19 April 2008. It was one more eloquent than the detail of anyone's scorecard.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks