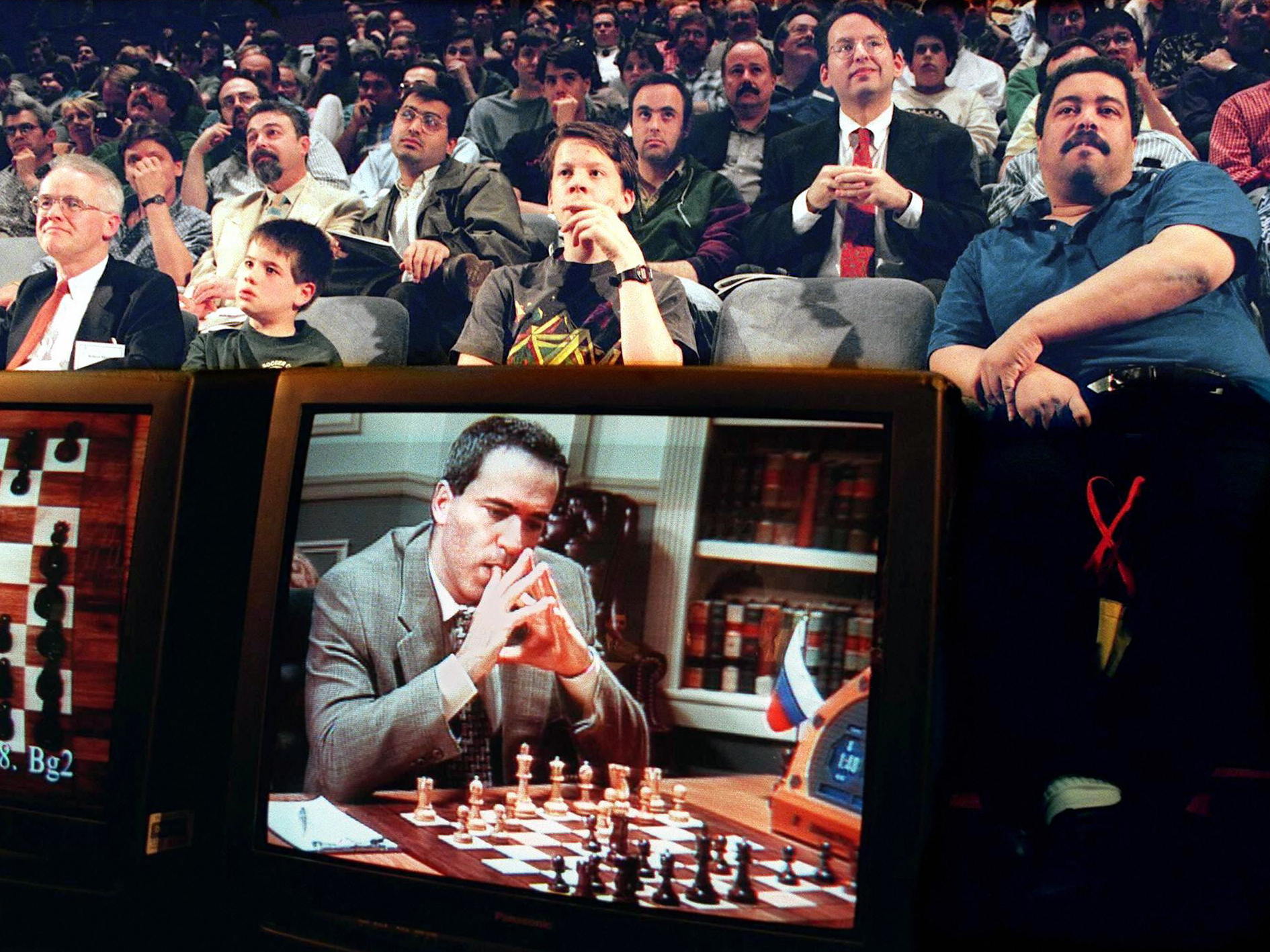

How Garry Kasparov’s defeat to IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer incited a new era for artificial intelligence

Russian grandmaster’s loss to an ‘alien opponent’ was a watershed moment for 20th century technology

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Garry Kasparov hated losing but in defeat, to an “alien opponent” incapable of fear or the faintest flicker of emotion, the youngest of chess champions and greatest of grandmasters made history.

The Russian’s 1996 and 1997 man vs machine matches against Deep Blue, an IBM RS/6000 supercomputer capable of crunching 200 million positions in the space of a second, wrote headlines around the world.

Although Kasparov won the February 1996 match in Philadelphia, his faceless foe took the opening game in a watershed moment for artificial intelligence and 20th century technology.

The computer, playing with the advantage of the white pieces, forced the Russian to resign on the 37th move after surrounding his king.

It was the first time a computer programme had ever beaten a reigning chess world champion under classic tournament rules, where players have hours to plan their strategies.

Kasparov sat on a raised platform opposite a video display terminal as a programmer received the moves over the internet from New York.

The second encounter held over nine days in a New York skyscraper, with Deep Blue’s software upgraded, was declared “The Brain’s Last Stand” by Newsweek magazine.

“The computer is an alien opponent and the characteristics of this opponent are very, very different from any human opponent,” Kasparov, then 34, had told reporters.

The swashbuckling Russian won the first game but cracked under pressure on May 11, 1997, the computer clinching the match with two wins, three draws and one loss.

“In brisk and brutal fashion, the IBM computer Deep Blue unseated humanity, at least temporarily, as the finest chess playing entity on the planet,” reported the New York Times.

“One small step for a computer, one giant leap backward for mankind?,” asked the Wall Street Journal.

Kasparov later said he had treated the $1.1 million event as a great scientific and social experiment but Deep Blue, whose two towers soon became museum pieces, proved “anything but intelligent”.

“The way Deep Blue played offered no input in the mysteries of human intelligence,” he told the DefCon hackers’ conference in a 2017 keynote address. “It was as intelligent as your alarm clock. Although losing to a $10 million alarm clock didn’t make me feel any better.”

Born Garik Kimovich Weinstein in Baku, now the capital of Azerbaijan, Kasparov adopted his mother’s surname at a young age after his father’s death.

He became a grandmaster at 17 and world champion at 22 in 1985 when the charismatic youngster beat Soviet establishment hero Anatoly Karpov.

The first match in Moscow between the two in 1984-85 lasted more than five months and was abandoned on health grounds after a record 40 drawn games, with Kasparov coming back from 5-0 down to 5-3.

Kasparov formed the short-lived Professional Chess Association in 1993, then retired as a professional in 2005.

A fierce critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin, he played an active role in the anti-Kremlin opposition protest movement when he lived in Moscow and even tried to run for the presidency.

In 2012 he became chairman of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation, succeeding former Czech president Vaclav Havel.

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments