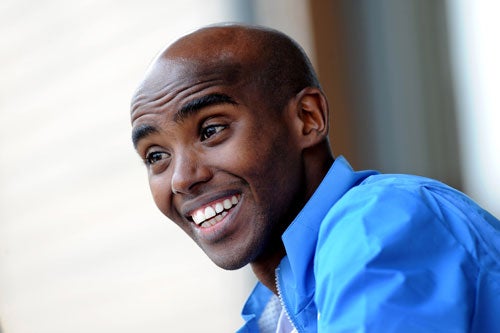

Brian Viner interviews Mo Farah

An engaging mix of west London and east Africa, the European 5,000 metres silver medallist has come a long way to be a Beijing contender – thanks in part to the generous encouragement of Paula Radcliffe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mo Farah was nine years old, a slight sprite of a boy, when he entered Oriel Junior School in Hanworth, one of south-west London's tougher suburbs, for the first time. He had arrived in England just weeks earlier from Djibouti in the horn of Africa and spoke hardly any English beyond the few phrases and sentences his father had taught him to see him through his first day at school. "Excuse me," was one. "Where is the toilet?," was another. But he had also learnt to say "C'mon then," not knowing that it could be misconstrued as provocation. On that first day at Oriel, he made the mistake of saying "C'mon then" to the hardest kid in the school. Farah smiles broadly at the memory. "He twatted me," he recalls. A fight erupted, in which the newcomer gave almost as good as he got. His fellow pupils were quietly impressed.

Last night, at an IAAF Grand Prix in Ostrava, in the Czech Republic, the same Mo Farah, now 25 and sounding as though he has lived in south-west London all his life, was preparing to run in the 5,000 metres against the wonderful Ethiopian runners Tariku Bekele and Abebe Dinkesa, and Augustine Choge, Eliud Kipchoge and Isaac Songok from Kenya. If he makes it to the Olympic final on 23 August he can expect even more formidable opposition, doubtless including Bekele's older brother Kenenisa, the world record holder. The challenges facing Farah are different now, but in some ways not nearly as testing as those first few months in a strange country, confronting a strange language.

As with so many high-achievers, it was an inspirational teacher who smoothed his path to success. From Oriel, Farah moved to Feltham Community College, where his sporting potential was quickly recognised by the PE teacher Alan Watkinson. But Farah's English was still limited, and his was one of the few black faces in a school populated mainly by white, working-class kids, making him an easy target for bullying. Nor was his own behaviour exactly irreproachable. "I remember a javelin lesson, the first lesson Mo had with me," Watkinson tells me. "Javelin lessons have to be strictly supervised for obvious reasons but I found him hanging from the football posts. I thought 'Hello, what have we got here?'"

What he had was a boy of prodigious talent, who became the best javelin thrower in the school "by some distance", indeed the best in practically every track and field discipline. He was also a decent footballer. But Watkinson knew where his real ability lay. "I remember seeing him in a cross-country race for the first time. He didn't win because he didn't know the way. He kept turning round to see that the others had gone off in a different direction. But his running was so effortless."

Watkinson used Farah's love of football to lure him into cross-country training, promising him a half-hour kickaround beforehand. His protégé duly won the English Schools cross-country championship in five consecutive years, and by the time Farah came back from the Youth Olympics in Florida in 1998, when he was 15, the ambition to be a full-time runner had supplanted the dream of becoming a winger for Arsenal. In 2006, the year he won silver in the European Championships 5,000m, and gold in the European cross-country championships, he was voted Britain's Athlete of the Year – the first distance runner since Brendan Foster 30 years earlier to claim that distinction, if only because so many votes were split, in the halcyon age of British distance running, between Sebastian Coe, Steve Ovett and Steve Cram.

Those three men are among Farah's heroes, no matter that they peaked before he was born. "I watch their races quite a lot on YouTube," he says. "They're unbelievable." Another hero is Muhammad Ali. "Yeah, I still have a poster of him in my room. The 'Rumble in the Jungle'? Fantastic." But his greatest admiration is reserved for Paula Radcliffe. "She's very special. She has supported me and still sends texts to me now and then. She never goes to the newspapers and says she's helping so-and-so, but a few years ago she quietly chose a few athletes she thought needed support in different ways, paying for them to go on warm-weather training or whatever. For me, she paid for me to take driving lessons. I couldn't drive but I had to get out to Windsor to train, which was a difficult journey without a car. I look up to her a lot. She's made me believe that anything is possible."

Farah trains these days at St Mary's College in Twickenham, which, on a warm day, is where we meet. He has just completed a lap of nearby Bushy Park, but the only sweat in the vicinity is on my brow, not his. He is an immensely engaging man, with a smile that could light up the Thames on a dark night, and, appealingly, is readier to discuss his frailties than his strengths, as well as his debts to others, beginning with Watkinson.

"It was Alan who started everything for me, and I'm still in touch with him regularly. But even a couple of years ago I was living in halls of residence here at St Mary's, being a lad and not really focusing. I was going out for runs but then I'd go out with my mates and come in at midnight. It was my agent who told me to look at the Kenyans, and then I went to live with them, while they were based here for the European season. That was the best decision I ever made in my life, after the decision to choose running. They train in the morning, come back, sleep, eat, then train again. And they eat sensible food, a lot of unga, which is a kind of maize. I realised that if I was going to have a chance, I needed to live like they did, completely dedicated."

Farah does have a chance now. He is a realistic Olympic medal contender and quite happy to acknowledge that he more or less constantly has China on his mind. "I've never been to an Olympics and of course it's every athlete's dream to go," he says. "People think that you're preparing for a few months before, but it's four years of hard work. So my first job is to stay injury-free and to get there, and then I've got to get through the heats. Sometimes the heats are harder than the final. But I'm very excited by the challenge."

And, just to leap beyond Beijing, does that excitement extend to London 2012? "Oh yeah. I'll be 28, 29 then, and hopefully at my peak. I don't know what event I'll be concentrating on then. I'm very comfortable at 5,000m now, but I would probably want to step up to 10,000m or even the marathon. We'll see what happens."

I venture that a marathon medal in 2012 would be a nice reward for Radcliffe, after shelling out for those driving lessons? He just grins, in his boyish way, offering a beguiling glimpse of what he must have been like as a child. I ask him what memories he has of life in Djibouti, and before that the Somalian capital Mogadishu, where he was born?

"Not many. I went back for a holiday quite recently, and I could hardly believe I used to live there. I spent six days in Somalia, and eight days in Djibouti, which was great. People are very close to each other out there. They're all either related to you or they think they're related to you. Everyone tells you that they're your cousin." He laughs, delightedly. "In Somalia I went running," he adds, "and this guy, this ordinary guy, kept up with me."

It is tempting for journalists to depict Farah's early life in Somalia as one of bare feet and mud huts, and he understands why, but it doesn't quite correspond with reality. "It wasn't like that," he says with an almost apologetic smile. "There are people like that but we lived in a normal stone house with my mother, grandparents and two younger brothers – there's another brother now. My grandfather worked in a bank and we had a comfortable life, not easy but not hard. My father was born in England – he grew up in Hounslow – but he went there for a holiday and met my mother. Then he came back to England so we didn't see much of him. That's why we came to Britain when I was nine, to see more of my father. But I remember his trips to see us in Africa. He used to bring me footballs, and once he brought me some shoes with flashing lights on. That was fantastic. I loved them."

And with that he leaves to train some more, no longer in need of lights on his shoes to illuminate the track.

Britain's 5,000m pedigree

*1912

George Hutson finished third to claim one of his two bronze medals at the Stockholm Games, finishing 31 seconds behind the winner, Hannes Kolehmainen, of Finland, who had won the 10,000m two days earlier. Hutson won his second bronze alongside Cyril Porter and William Cottrill in the 3,000m team race. Called up for the First World War, he was killed in action in September 1914.

*1956

In the absence of the powerful Hungarian Sandor Iharos due to the Soviet invasion of his country, the 1955 BBC Sports Personality of the Year, Gordon Pirie picked up silver and Derek Ibbotson bronze. The Soviet runner Vladimir Kuts finished 75 yards clear in first place. Ibbotson was awarded an MBE in the most recent New Year's Honours list.

*1972

Ian Stewart profited at Munich when the American Steve Prefontaine, having predicted that he would run the final mile in under four minutes, picked up the pace with four laps to go. As he faded, the great Lasse Viren swept past to complete a 5,000m/10,000m double, with Mohamed Gammoudi in second. Stewart pipped Prefontaine to the bronze, 1.19sec behind Viren.

*1912

George Hutson finished third to claim one of his two bronze medals at the Stockholm Games, finishing 31 seconds behind the winner, Hannes Kolehmainen of Finland, who had won the 10,000m two days earlier. Hutson won his second bronze alongside Cyril Porter and William Cottrill in the 3,000m team race. Called up to the Great War, he died in action in September 1914.

*1956

In the absence of the powerful Hungarian Sandor Iharos thanks to the Soviet invasion of his country, the 1955 BBC Sports Personality of the Year, Gordon Pirie picked up silver and Derek Ibbotson bronze. The Soviet runner Vladimir Kuts finished 75 yards clear in first place. Ibbotson was awarded an MBE in the most recent New Year's Honours list.

*1972

Ian Stewart profited at Munich when the American Steve Prefontaine, having predicted that he would run the final mile in under four minutes, picked up the pace with four laps to go. As he faded, the great Lasse Viren swept past to complete a 5,000m/10,000m double, with Mohamed Gammoudi in second. Stewart pipped Prefontaine to the bronze, 1.19sec behind Viren.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments