World Cup 2018: Russia's clash with Spain evokes memories of one of the most politicised football matches ever

With controversial nationalist celebrations, matches that have so many extra diplomatic dimensions and then its entire host setting, Russia 2018 may well be the most politicised international tournament of all time - so it’s probably somewhat fitting it will now feature a re-staging of one of the most politicised fixtures ever. Even then, there’s actually a story that this remarkable World Cup won’t be able to live up to. The undercurrents of Russia 2018 can’t come close to matching the overt politicisation of the meeting between Spain and USSR in the 1964 European Championships.

This was a fixture that really had everything swirling around it, from outright state propaganda and worry about spies to direct dictatorial interference, as well as a proper contest between the early 20th century’s two dominant political ideologies. This, as news agency AFP reported at the time, was when “football was the victim of the Cold War”.

This was also a story with two legs over half a decade, only adding to its scope and scale.

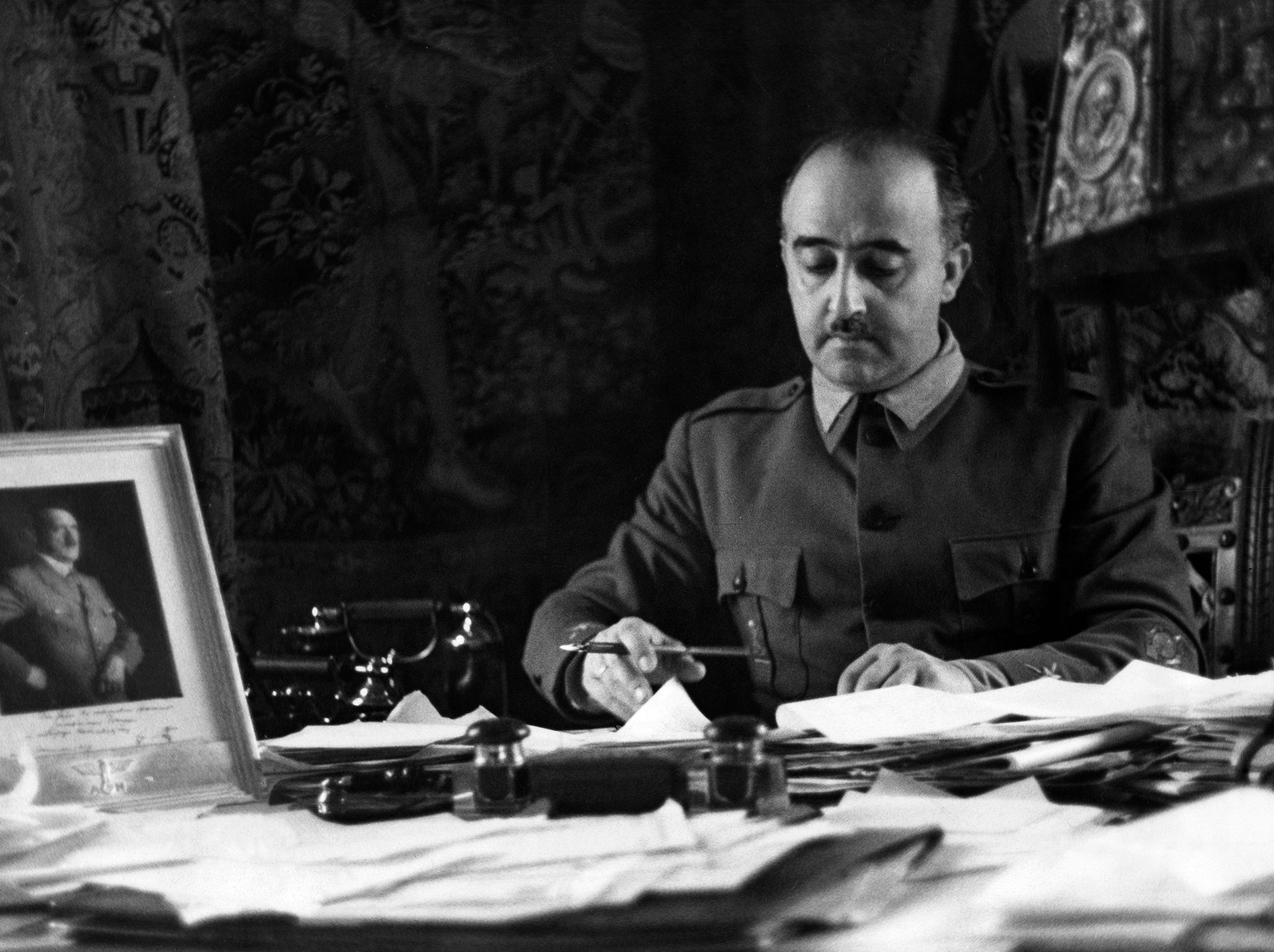

It wasn't so much the Spanish national team against USSR as General Franco against Russian premier Nikita Khruschev - with both actually getting involved - and communism against fascism.

It began when Uefa tried to expand the scope and scale of the game in 1959, by finally devising a continental European competition to match the World Cup.

With West Germany, Italy and, of course, England opting out of the maiden 1960 event, however, that left just 17 sides - and ensured the pick of them was Spain.

That was because this was a Spain yet to endure four decades of underperformance, but who were instead energised by the Real Madrid side that were in the process of winning five consecutive European Cups. Their influential Argentine playmaker Alfredo Di Stefano was able to feature due to old eligibility rules - having missed the 1954 and 1958 World Cups - and he was finally able to match up with Barcelona stars Luis Suarez and Ladislao Kubala.

This was set to be Spain's time, with that sense of opportunity only bolstered by a supreme 7-2 two-legged win over Poland… until they were drawn against another side from the Iron Curtain in the quarter-finals, and the country that drew the curtain: the Soviets.

Very far from a fully-formed a competition at that point, the early European Championships didn’t even represent a modern tournament until the last three matches, when it would move from a two-legged knock-out to one of the remaining countries involved hosting the semi-finals and final.

That would mean a trip to Moscow for Spain as well as the USSR visiting Madrid - a prospect that so perturbed General Franco’s regime he eventually pulled the national team from the tie just two days before the trip.

Details that have come out since then have cast further doubt about why that may have been the case - even if it was ultimately all about the glory of Spain, and the fascist politics that the state was founded on.

A much savvier regime in terms of media at that point, the Soviets instantly realised the propaganda value of victory. They sent the squad to a preparation camp in East Germany and the Netherlands, and later put them up in accommodation normally reserved for members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. This was how seriously it was taken. This, after all, was the true enemy.

The USSR and Franco’s regime had cut off all relations since the Spanish Civil War, when over 2,000 Soviet troops were sent to support the Republican side. A few years later, 18,000 Spanish soldiers were sent to the eastern front of the Second World War with the Nazis to fight communism.

With the battle having long since moved to new areas, one major concern among the Franco regime about a Soviet visit to Madrid regarded the potential infiltration of Russian spies. There were then the symbolic problems of the Hammer and Sickle flying over the centre of this fascist state at the Bernabeu, an idea that was said to repulse the dictator. So what would the prospect of a Soviet victory do?

This may have had more do with the withdrawal, as many sources since have said that Spanish scouts were greatly concerned by how good the USSR looked in the 4-1 defeat of Hungary in the preliminary round.

It’s just that the feeling was mutual. In a brilliant piece on the 1960 match, Vadim Furmanov unearthed a curious newspaper interview with Andrey Starostin, executive secretary of the Soviet Football Federation. The official said Spain were every bit as good as the brilliant Brazil team that had launched their era of success with the 2-0 1958 World Cup win over the USSR, and described Di Stefano as “a centre forward for all the ages”.

Starostin was in for a shock after that, but not from Spain. At the next meeting of the football federation, the following censure came: “Instruct comrade Starostin to inform the representatives of the sporting press about the harmfulness of exaggerating the qualities of the Spanish team and of giving complimentary accounts about the style of play and the skill of the Spanish players.”

This was apparently bad for national morale, but not as bad as news of another Spain win, this time 3-0 over England in a friendly. Pravda reported that the FA had put out a youth team, something that was a total lie.

It wasn’t so much about blinding people to the truth, then, as to who would blink first. That - by a distance - was going to be Franco’s regime. The Spanish state were already making moves to change the game, although one supposed suggestion was to move it to neutral grounds, or even play both legs in Moscow - something the USSR actually rejected.

As this rumbled on, news about the match suddenly stopped appearing in the Spanish papers in the days building up to the 27 May fixture, until the players were finally told they would not be travelling to Moscow two days beforehand. Uefa had no option but to banish Spain from the competition, and fine them 2m Swiss Francs.

The players were furious, not least Di Stefano, who was conscious of his international legacy given this opportunity. When he confronted Spanish federation president Alfonso de la Fuente-Chaos, the response was simple.

“Orders from above. Franco said no.”

The Soviets meanwhile said an awful lot in response, mostly lording it with Nikita Khruschev going so far as to directly joke that it was an “own goal” from a “right-sided” player.

“The whole world is laughing at [Franco’s] latest trick. From his position as the right-sided defender of American prestige, he has scored an own goal by banning the Spanish footballers from competing against the Soviet team.”

Soviet media meanwhile expressed solidarity with their fellow workers in the Spanish quad, but said that “the fascist government had “feared the team of the proletariat”.

The Soviets went on to win that Euros, beating Yugoslavia 2-1 in the final thanks to an extra-time goal from Viktor Ponedelnik - and a naturally assured performance from legendary goalkeeper Lev Yashin. This further rankled with the Spanish players, as they felt they had the beating of USSR but couldn't even express it publicly. The episode was to be wiped from public memory, although the regime did not forget the fall-out.

Franco had made a huge error, but wouldn’t make it twice.

There would instead be a huge volte face. Although they could have banned Spain from the competition, Uefa instead faced a huge campaign from the Madrid government to host its next tournament in 1964.

Franco had belatedly realised the power of such an event, with some Spanish media later likening it to Berlin 1936, but he didn’t realise too late.

It also wasn’t too late for the team, either. Although Di Stefano had moved on, Spain still had a supreme spine led by European Cup and Ballon D’Or winner Suarez, by then of Internazionale.

With the playmaker directing things, the Spanish powered through the tournament… where they would finally meet USSR in the final. This time Franco said yes. He couldn’t do anything else. He had already invested too much in it.

The stakes were heightened, but so was Spanish preparation and pageantry.

The build-up to the game was filled with talk about “the path to the glory” and all of the old bombastic tropes of fascism. There appeared a new hysteria, not least when Franco - accompanied by his wife and vice-president Agustin Munoz Grandes, who had actually fought in the Blue Division against the Bolsheviks in the civil war - entered the Bernabeu on 21 June 1964. The grandiose stadium immediately erupted, with 120,000 people chanting “Franco! Franco! Franco!”

Those chants reached a cacophony after six minutes, when Barcelona’s Chus Pereda opened the scoring, only for Galimzyan Khusainov to immediately equalise.

There followed 76 tense minutes for Franco and the regime, as all of their plans and attempts at control were subject to the whims of the game. Until, on 84 minutes, Real Zaragoza’s Marcelino gave the regime their moment of victory. And that really was made clear.

As Barcelona’s Ferran Olivella went up to collect the trophy from the dictator’s outstretched hands, there then followed the coup de grace.

“We offer this victory first of all to Generalisimo Franco, who came this evening to honour us with his presence and energise the players, who have done the impossible in offering el Caudillo and Spain this sensational triumph”.

Vladimir Putin can still only dream of such a tribute. And even this World Cup still has some way to go match the politicisation of the 1964 Euros.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks