Theo Walcott’s decline represents a slow ebb of the ‘Golden Generation’ and the ridiculousness of backing ‘The Future’

England have invested in youth before and built it up to an unattainable level, which is worth remembering when the 2018 World Cup begins next month

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

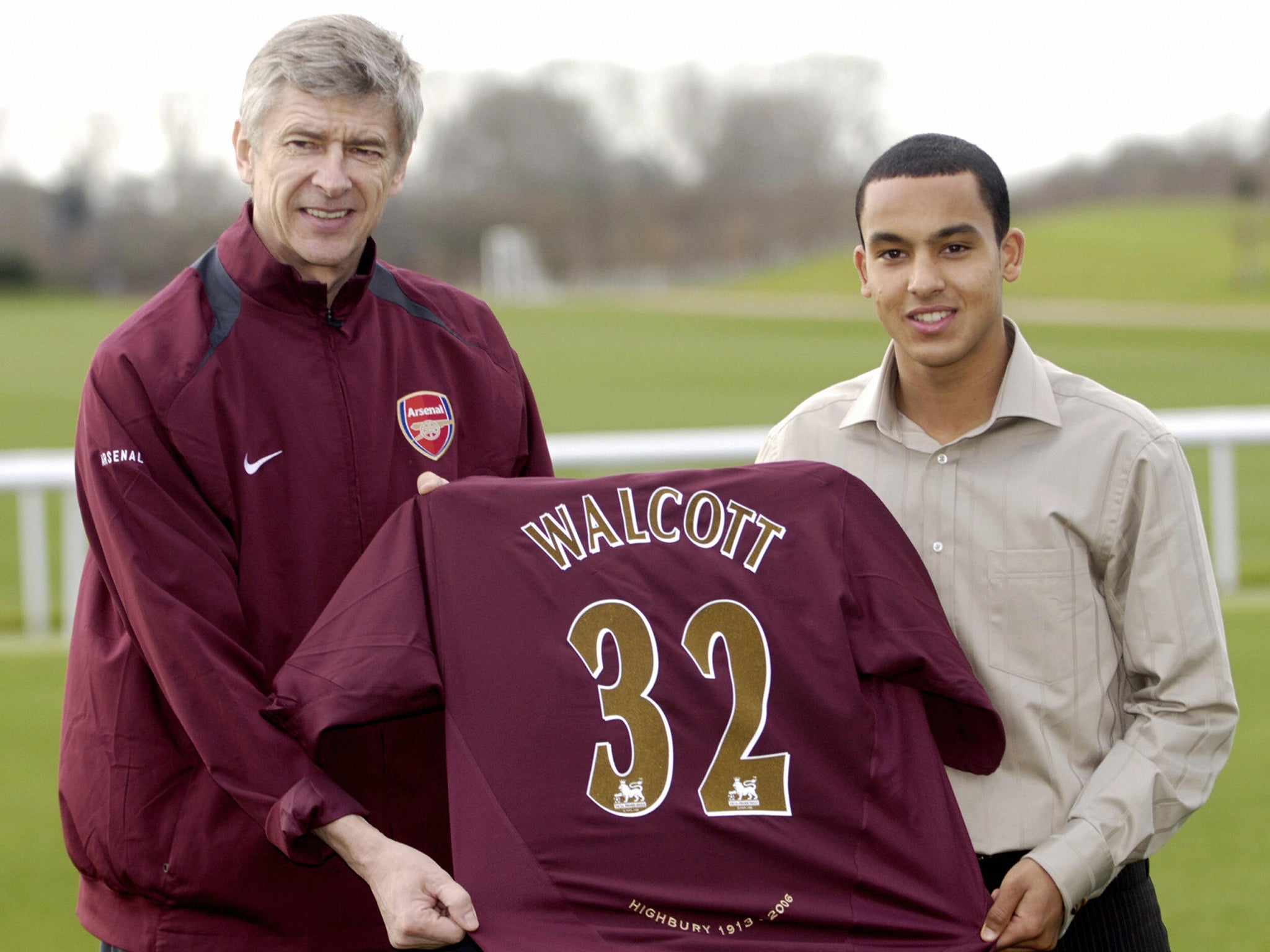

Your support makes all the difference.Theo Walcott had just finished his driving theory test, and was calling his father Don to let him know. But there was an even bigger piece of news waiting for him on the other end of the line. The Football Association had just been in touch. The month was May 2006, and Walcott was being called up to an England World Cup squad for the last time.

Twelve years on, by contrast, there was no real news to break. No ‘difficult’ phone call. No tears. No virtual pitchforks, no #justice4theo social media hashtag, no tabloid whispering campaign, no Gazza-style meltdown. After all, Walcott has not played internationally since 2016, and so as Gareth Southgate this week unveiled an England squad based on youth, excitement, pace and some wonderfully vague notion of The Future, nobody – least of all, you suspect, Walcott himself – was under any illusions that he would be part of it.

And so that, you probably have to imagine, will be that. After being harshly left out by Fabio Capello in South Africa, and forced out by injury four years ago, it seems likely the only glimpse we ever catch of Walcott at a World Cup will be those surreal images from Germany, in which the teenage Walcott and his girlfriend Melanie strode through Baden-Baden wearing glazed and bewildered expressions, like exchange students who had lost the rest of their group and somehow ended up in a Sport Relief sketch.

For the teenage Walcott was not so much a footballer as an idea: a lush, orchestral reverie of billowing potential, scampering feet, gilded dreams, some wonderfully vague notion of The Future. In 2008, when the Beijing Olympic torch relay arrived in London, Walcott was the only footballer selected to carry it. When his manager Arsene Wenger claimed he was better than Lionel Messi at the same age, nobody laughed.

Never mind that his finishing needed work and his decision-making left plenty to be desired. Just look at that pace! “One of the most dangerous players I have ever played against,” Messi himself once admitted, and on a good night – of which there were more than a few – Walcott could look more than worthy of the Arsenal No14 jersey he inherited from Thierry Henry. Even with hindsight, it’s hard to argue with 116 career goals, two FA Cups, countless North London derbies. England vs Sweden at Euro 2012. Arsenal vs Barcelona in 2010.

And in a sense, Walcott’s gentle decline says as much about the evolution of the game as it does about Walcott himself: a gliding straight-line runner in a sport that these days more readily resembles a series of high-impact collisions. We often talk about footballers being “blessed” with pace, but perhaps conversely Walcott was cursed by it: a Fifa-friendly player in a game that demanded a lot more than simply running with the ball while holding down R2. The modern flank is a place for 800-metre runners, not sprinters.

Yet the parallel of Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, a player who since leaving Arsenal has discovered new gears, new weapons, new options, points to a different and more systemic sort of failure. As with many other promising attacking talents of the age, Wenger never really seemed to possess a clear vision of how he saw Walcott progressing, whether to rein him in or to let him loose. Eventually, like a £40 T-shirt you end up wearing in bed a decade later, he cut him adrift.

Perhaps, then, if there has been a lesson to Walcott’s career it is in both the power and the futility of dreams. The departure of Wenger marks the closure of Arsenal’s dream factory, a turning out of the lights, a capitulation to cold hard logic. Similarly with England, the appointment of Southgate and the slow ebb of the golden generation marked the point at which we finally made peace with our more modest status. We know our place in the world now, and it’s Harry Maguire in a back three. Walcott, too, knew his place, and it was playing mid-table football under Sam Allardyce at Everton. Maturity makes pragmatists of us all in the end.

I wonder, though, if we didn’t all sell ourselves a touch short. Barring a remarkable resurgence, Walcott will end his England career with 47 caps. Just three of them ended in defeat: none of them in a competitive match, none of them on foreign soil. His win percentage in an England shirt – and this is so remarkable I double-checked it to make sure it was true – is the highest of any England player who has won 40 caps or more. Walcott is, quite simply, the most successful England footballer of this or any other age. I don’t know what that tells us, but it’s not nothing.

It’s a funny thing about young footballers. We laud them to the skies on their emergence. We all want to say we saw them first. We plead for them to be given time, even whilst trying to envisage the champion into which they will develop. And yet when, remarkably, they fail to live up to the hype, somehow it’s always the player’s fault rather than the hype. As with so many other hotly-tipped prodigies, it’s tempting to think about Walcott in terms of failure, inadequacy, loss. Perhaps, instead, a player who first took shape as a brilliant idea remains just that: a sunlit extrapolation, a figment, a blurry vision of pure untrammelled speed that really only existed in our heads.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments