Qatar’s World Cup legacy has to go beyond a spectacular vanity project – but will it?

With 100 days to go to the big kick-off, Miguel Delaney explores how the most controversial World Cup in history came to be – and the human rights concerns that plague it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

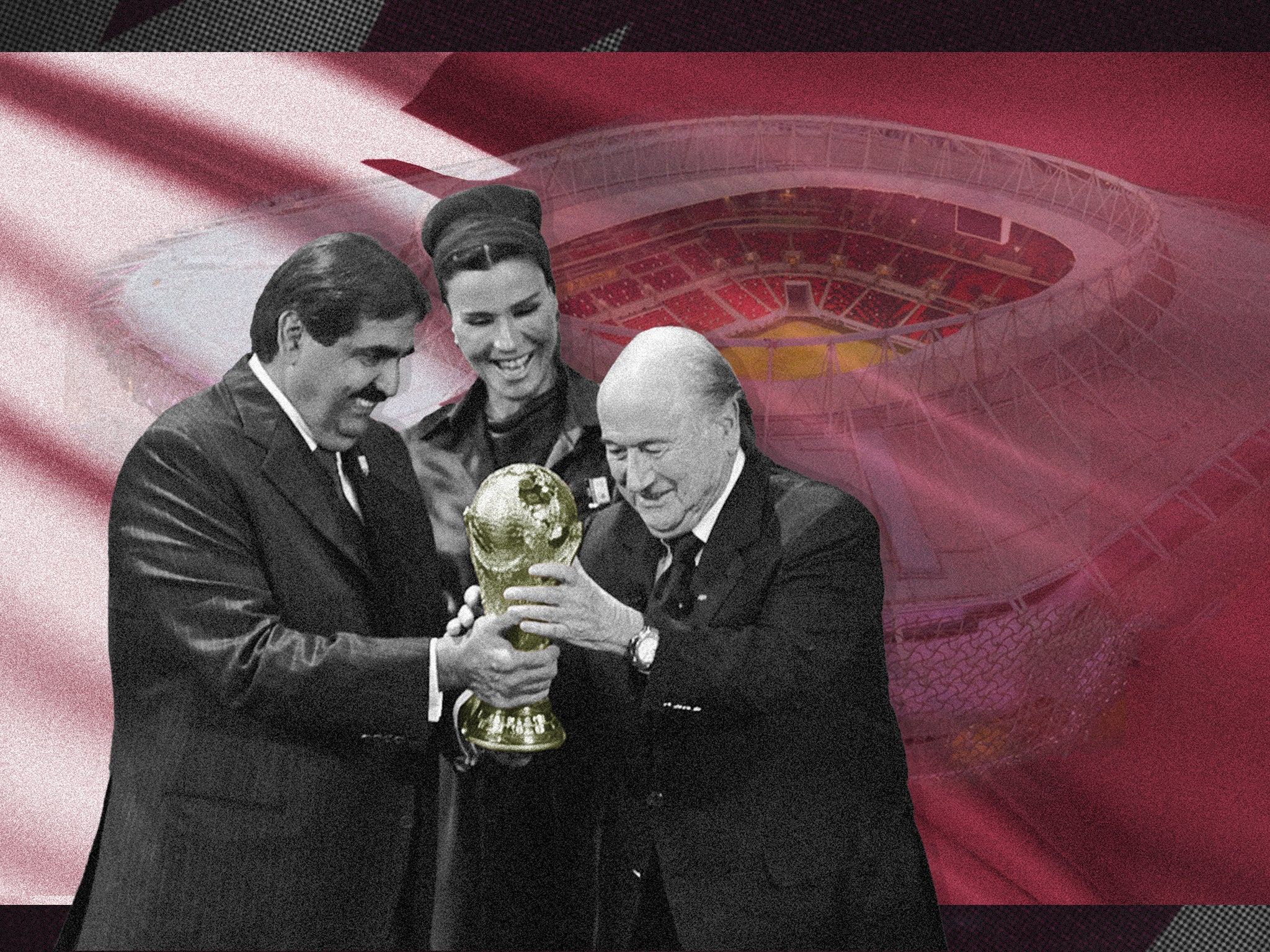

Your support makes all the difference.As the former Fifa president Sepp Blatter announced that Qatar would host the 2022 World Cup, the responses within the Zurich auditorium on that snowy Thursday in December 2010 revealed much more. They also hinted at what was to come.

The Qatari royal family jumped in jubilation, some in “disbelief” that it actually happened. Their cheers echoed around the auditorium, though, because almost everyone else was stunned. A few of football’s most powerful figures were enraged.

In the middle of it all, one man was relieved but not surprised. Mohammed bin Hammam, the driver of Qatar’s bid, had been ticking off the votes throughout. As early as the first round, Qatar had received 11, requiring just one more to seal victory.

It was as much a formality as a shock.

This was because, to use the leaked description of former Fifa secretary general Jerome Valcke, Qatar had “bought the World Cup”. Mr Valcke later claimed he was speaking metaphorically. It is estimated the state spent close to €200m (£169m) on the bid, almost five times more than the next most costly campaign. That was Australia, who received just one vote.

As a consequence of that victory, and a complete change to hosting plans that Fifa’s own report described as “high risk”, Qatar has committed to spending £5.2bn on new stadiums and £150bn on infrastructure around the World Cup.

That project has required a construction plan that has made this tournament perhaps the most controversial sporting event in history, certainly since the 1980 Moscow Olympics, due to a system that inherently involves the abuse of migrant workers. Qatar disputes the figure of 6,500 deaths that The Guardian has put forward, but the only reason they can argue that is because the state has so far refused to investigate the true numbers.

It has all involved so much money, so much controversy, so much human suffering… and for what?

The question of why Qatar wanted to host the World Cup is more relevant now than ever, particularly given the deeper discussion over whether the motivations are the same. The world, 100 days out from the start of the tournament, is a very different place to what it was on 2 December 2010.

Qatar itself was “probably the Gulf state about which the least was known” on that afternoon, according to the human rights organisation FairSquare’s Nick McGeehan. That has drastically changed. In the moment of victory, the Qatari delegation gave all the official platitude about hosting the World Cup.

“Thank you for believing in change,” Sheikh Mohammed said breathlessly. “Thank you for believing in expanding the game. Thank you for giving Qatar a chance, and we will not let you down. You will be proud of us, you will be proud of the Middle East and I will promise you this!”

Much was made at the time of how the event would bring “billions of people to the Arab world”, while also bringing the Arab world together. Qatar initially hoped to attract support from the entire region, as a “unity bid”.

There is quite a tragic irony to that, given what has actually happened. It should be acknowledged that there is genuine merit to the idea of hosting the World Cup in the region for the first time, and there could have been something special about it.

Instead, many make the argument that it was a significant factor in the Gulf blockade which lasted for three and a half years from 2017 – where Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt cut ties with Qatar accusing it of supporting terrorism among other claims – such was the resentment within Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates about Qatar’s rising profile. On the other side, though, the World Cup probably played its part in helping Qatar to come out of the blockade stronger.

The apparent contradiction to that reflects the more complicated elements to this, far beyond the state’s genuine love of football and the desire to spread the game.

Qatar had been seriously investigating the purchase of Manchester United before the bid, but couldn’t make progress with Old Trafford club’s Glazer family owners. There were also more tentative discussions around Liverpool, Tottenham Hotspur and Arsenal, who the “Father Emir” is said to support.

It is no coincidence all of this came in the period after Gulf rivals Abu Dhabi bought Manchester City in 2008, a takeover that also represented a touchstone moment in pushing football into a new geopolitical age.

Qatar, in the words of many involved, wanted their own prize. They ended up initially going for much more traditional “sportswashing”. That was the hosting of a great event.

All of this was part of a more sophisticated and longer-term plan to diversify their gas-based economy, reposition the state in the eyes of the world and - as much as anything - increase security.

Sport was seen as central to this, because of its social and emotional power. Inside Qatar, an excellent new book by John McManus, quotes one senior figure who compares the state’s current status to Bahrain and Oman.

“Have you ever seen a headline in any newspaper about either of those countries?”

The hierarchy understood that the state being a world-class sporting centre - to go with grand statements in business and arts – helps form the image of a mature and modern country, regardless of any bigger questions about human rights or how it was all put together.

The plan was still pushed along by a somewhat unlikely source.

The Ugly Game, by Heidi Blake and Jonathan Calvert, recounts an extraordinary exchange in the build-up to the bidding process for 2022. Mr Blatter was having a private dinner with the Father Emir, Sheikh Hamad, and Mr Bin Hammam, when he felt a thank you was due for the latter standing aside as a Fifa presidential candidate in the years previously. Blatter suddenly declared: “We are going to bring the World Cup to Qatar.”

Mr Bin Hammam was stunned. He felt it was impossible, and impractical.

The Emir’s eyes lit up. He felt it was perfect, a brilliant idea to bring the entire project together. Mr Bin Hammam next just had to bring the votes together. It created immense pressure.

It also set in motion a remarkable chain of events that has reshaped football, and caused ructions throughout the Gulf. The Emir’s will – by now unshakeable – was strengthened by the fact these aims fitted into Qatar’s long-running acute political competitiveness with Saudi Arabia and UAE. Many experts on the area feel this motivation has been drastically underplayed in much of the discussion around 2022.

That is despite the fact that, literal days after the announcement, the Arab Spring swept through the region. It widened differences, particularly as regards claims that Qatar was a sponsor of groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, who both Saudi Arabia and UAE regard as terrorists.

Tensions eventually developed into the Gulf blockade, which one source says “many argue might not have happened in the first place if Qatar hadn’t won the right to host the World Cup”. There was even one period where it was feared Saudi Arabia would invade.

And yet this was where 2022 offered benefits beyond its prestige. As one expert on the area argues, “it’s lot harder to invade somewhere if they’re hosting a World Cup”. Qatar deftly used its new position of influence to stand firm.

The image is still ragged, though.

By far the biggest discussion surrounding the World Cup has been the abuses suffered by migrant workers. Human rights groups remain aghast that, over 4,000 days since the tournament was announced, and 100 days until it starts, Qatar’s much-criticised labour system remains “effectively the same”.

The hierarchy now constantly point to how Kafala – a private labour sponsorship system – has been abolished. In meetings with football figures, state figures insistently ask why they would have a World Cup “if we didn’t want to expose ourselves”.

Yet McManus’s book outlines how Qatar was actually taken aback by the scale of criticism. Human rights groups state that, although Kafala may have been abolished in technical and legal terms, it has made little tangible change to the constrained lives of workers. Numerous reports outline ongoing abuses.

“As you can see with the Qatar World Cup, it has to some extent put them on the map, but it has not in any sense been a risk-free venture,” McGeehan argues.

Peter Frankental, Amnesty International UK’s economic affairs director, concurs.

“If hosting the World Cup was originally a means for Qatar to rebrand itself and generally raise its profile, it’s likely that the aim now includes a successfully-staged tournament that avoids any detailed discussion of Qatari human rights issues.

“Fifa should have insisted on human rights clauses when assessing Qatar’s hosting bid and it must now ensure the World Cup legacy isn’t left to chance – including by financially supporting a workers’ compensation fund.

“The Qatari World Cup needs to be judged not just by the quality of its facilities and the television spectacle, but also by whether it actually leaves a legacy of improved human rights for its own citizens and Qatar’s huge number of hard-pressed migrant workers.”

Now, just 100 days out, there is set to be one major change to the tournament. The opening game will be moved to the previous day, so Qatar play in the very first match.

It would also greatly overshadow the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix on the same day. That might also show what this is all really about.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments