Wayne Rooney may never recover from his latest very public humiliation

After a stellar playing career, Rooney did not need to be a manager. But he took on the role regardless, in part to prove his intellect to those who doubted him, writes Jim White. His sacking after just 15 matches is the latest example of what could, should or might have been for the best English player of his generation

Wayne Rooney didn’t stay long at Birmingham City. After just 15 matches in charge, only two of which ended in victory, he was relieved of his duties as manager on Tuesday. Three months he had been the boss, just about enough time to learn the name of the tea lady. But then, nobody can be surprised by the swiftness of his departure. And among Birmingham’s supporters, there was considerable relief. Now, finally, the club could get a proper manager in.

Because the fact is, Rooney was all along a fantasy appointment, recruited on his name and celebrity, not his accumulated wisdom or tactical nous. For many it was always a laughable idea to put him in control of the club, one which really should lead to the defenestration of the man who made it, the CEO Garry Cook. But naturally, this being football, Cook stays in, apparently immune to the comedy value of his decision-making. And for Rooney, this might well prove to be the sacking which finishes his attempts to make a career as a manager almost before it has begun. Let’s just say, after the Birmingham debacle, the queue for his services will hardly be stretching around the block. And with that very public humiliation, the damage to his self-esteem and sense of purpose could prove substantial.

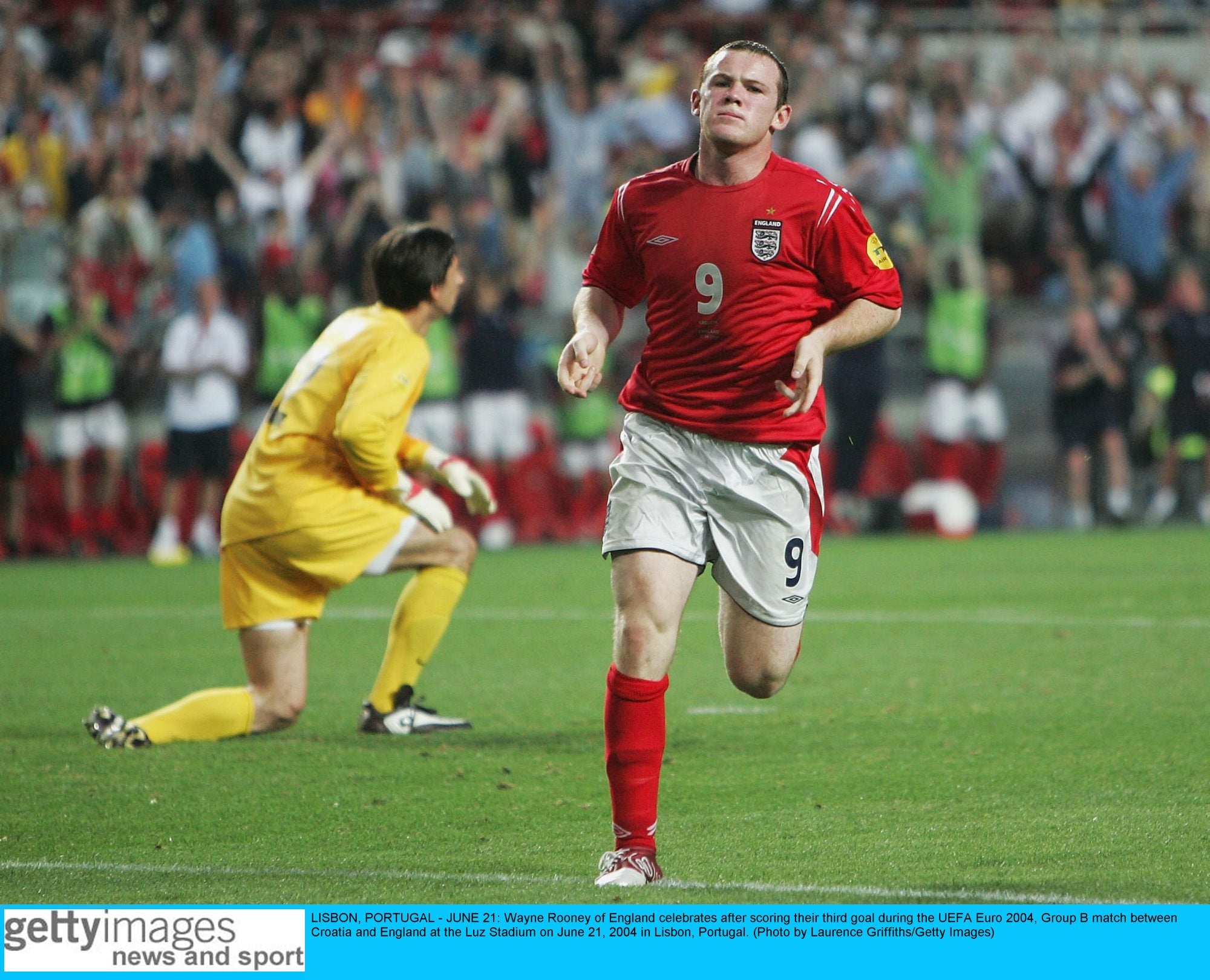

What a contrast it is to his time as a player when everything came easy to him. The most talented English footballer since Paul Gascoigne, from the start he played as if still on the streets of his Merseyside youth, his natural ebullience allied with a bullish refusal to yield allowing him to illuminate the pitch with breathtaking interventions. Next summer will mark the 20th anniversary of the moment he etched his name on the public consciousness, when at the 2004 Euros his extraordinary ability looked as if it might take England to their first trophy since 1966. Injury, however, intervened. And without his bravado, England proved to be an empty vessel.

Still, soon transferred to the then leading club in the land Manchester United, he was quickly accumulating silverware, his partnership with Cristiano Ronaldo securing European and domestic trophies apparently at will.

Interestingly in those early days, he was reckoned the superior talent to Ronaldo. But what soon became clear was that while the Portuguese took an ascetic approach in his determination to realise the genius within him, Rooney was happy to play for fun, with a pint and pie reckoned suitable reward. It meant for England, all that early promise was never adequately fulfilled. For sure, he briefly held goalscoring records for his country, but he also captained the side through its worst period of the modern era, culminating in the humiliation against Iceland in the 2016 Euros, when, 12 years after his joyous introduction, he looked a man weighed down by responsibility.

This was the thing about Rooney: the ease of his youthful prowess cast a doleful shadow over his later years. For sure he enjoyed a stellar career, yet it was forever undermined by what could, should, might have been. He was good, but he had the ability to be the best. Questions about his attitude, his diet and his application forever hovered about him. More to the point, there was widespread disparagement of his intellect. Which was not helped by how, in an attempt to put a protective shield around him, those in charge of his schedule maintained strict control over his output.

The unintended consequence was he was never able to be himself, forever nervous in interviews about saying the wrong thing, seeking protection in dullness. Those gifted the rare opportunity to get close to him found him lively, alert, funny. But for the wider world, he was never allowed to show that.

In part that was what drove him to become a manager: the desire to show the world that it was wrong about him. Hugely rewarded as a player, he need not have worked again when he retired. He could have demonstrated his engaging side as a pundit. But what he wanted to do was prove – to himself as much as the rest of the world – that he had the intellectual bandwidth to be a manager.

And initially, he went about things in the right way. At Derby County, his first job in the dugout, he was an assiduous presence, helping the young players to develop, demonstrating a real commitment to the cause even as the finances were collapsing around him. Winning, though, proved harder: he was unable to keep the side in the Championship after they had been deducted 21 points for monetary mismanagement. It was no surprise when he left the club after relegation.

Keen to continue his development, he went to Washington to run DC United, the side he played for in his dotage. But with his wife Coleen facing a lengthy court case brought by Rebecca Vardy following the Wagatha Christie social media comedy, his family remained in England. As he demonstrated by attending every day of the trial, determined to give public support to his wife, he is at his best with her by his side. Living in America alone took its toll. Separated by the Atlantic as he went about his work, he was morose and lonely, increasingly comfort-eating and drinking. At the end of 2018, he was arrested for public intoxication at a Washington airport. And after failing to take DC to the MLS play-offs last year, he left by mutual consent.

Then, back in September, Birmingham offered him a speedy return to the business. Even if it raised eyebrows – and hackles – everywhere, it is not hard to understand why Rooney took the job. Within a 90-minute drive of his substantial Cheshire home, from where he could enjoy Coleen’s company and keep an eye on the progress of his son Kai, now signed on at Manchester United’s academy, it made perfect geographical sense. Even more encouraging, unlike most managers taking on a new role, he was not inheriting a mess. The club were doing well under their previous manager John Eustace, the new owners had promised money to upgrade the squad, this was a real chance to prove that his faith in himself was not misplaced.

But while it looked a plausible opportunity for him, for the rest of football it appeared an appointment driven largely by the attempt to increase Instagram followers. The claim made by Cook at the time he was given the job was that he was the harbinger of a new order, the man who would upgrade the playing style, ready the club for a charge to the Premier League was soon shown to be an empty boast. Because almost from the off he found the going irredeemably tough. Like his mates from England’s golden generation, he discovered that communicating his ease on the field was not a simple process, the gap between knowing what to do and getting others to do it proving an insurmountable one. Just as Steven Gerrard, Frank Lampard and Gary Neville have come to recognise, it is so much easier to sit in a studio pontificating than it is to get a team to win.

It was, thus, always a reputational risk. The fact his time in charge at St Andrew’s has matched Liz Truss’s tenure at 10 Downing Street in its brevity, has cast a damaging pall over his past achievements. His departing statement, issued via the League Managers Association, was more than a little forlorn in its tone.

“Time is the most precious commodity a manager requires and I do not believe 13 weeks was sufficient to oversee the changes that were needed,” he wrote. “Personally, it will take me some time to get over this setback. I have been involved in professional football, as either a player or manager, since I was 16. Now, I plan to take some time with my family as I prepare for the next opportunity in my journey as a manager.”

The chances of another opportunity ever coming his way, however, now seem vanishingly small. For a man for whom football always appeared so easy, failure is painful indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks