Lionel Messi is the greatest player of his generation – but Diego Maradona debate will always remain

Maradona’s brilliance might have been far more volatile, but his feats with Argentina and Napoli are unmatched

The statement has been repeated so often in the wake of Lionel Messi’s ugly fall out with Barcelona and subsequent flirtation with Manchester City that it seems to be an unchallengeable truth. “Messi is the best player the world has ever seen.” To deny it has become heresy.

The thought of the brilliant Argentinian at the Etihad and playing in the Premier League is a thrilling notion. The 33-year-old has undoubtedly been football’s dominant figure in the 21st century and arguments about the relative greatness of Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo have been put to bed. The coruscating Portuguese is a notch below his bitter rival.

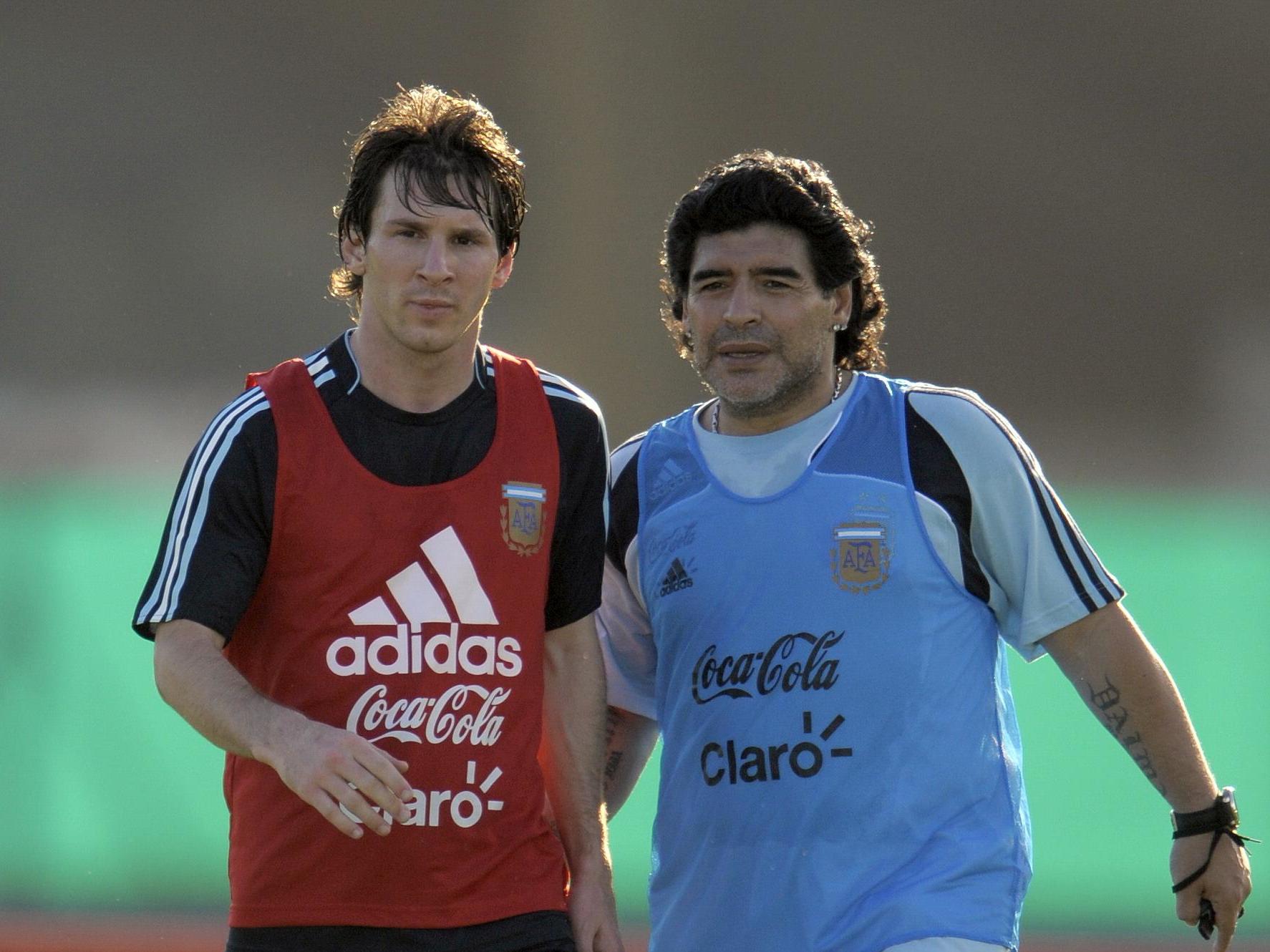

Messi’s elevation to the head of the sport’s pantheon is blocked by only one man: Diego Armando Maradona. The malign imp who emerged from the slums of Villa Fiorito in the 1970s had the unpredictable, unnerving charisma of a poltergeist. His ability was supernatural. In a game of fantasy football for the ages, it would be foolish to overlook Maradona if you had the first pick.

Messi is a safer selection. Genius has rarely been so stable and sensible. Maradona was as much a danger to himself as the opposition. It is remarkable that a man so prone to self-destruction achieved so much.

Advocates of Messi can bog down any debate in a landslide of statistics. Football is poetry, however, and not maths. It needs interpretation and has no certainties.

In the age of the superclub, Barcelona have been a bespoke vehicle designed around their talisman’s strengths. Messi’s watercarriers have been good enough to be central figures if they plied their trade anywhere other than the Nou Camp. One of the more fascinating aspects of any potential move to City would be to see how he operates in a team that has not been created in his image.

Maradona never had such luxury. When he arrived in Catalonia in 1982, Barcelona and La Liga were very different entities. The title race was not a closed shop between Barca and Real Madrid and the savagery of the tackling was beyond anything Messi would recognise. In September 1983 Andoni Goikoetxea, the centre back for the reigning champions Athletic Bilbao, broke the Argentinian’s ankle with a disgraceful challenge from behind. The boot that snapped Maradona’s ligaments was displayed in a case in the Butcher of Bilbao’s living room, taking pride of place with his two title-winning medals. Goikoetxea had previously badly injured Bernd Schuster, another of Barca’s big-name imports. The German’s knee was never the same after he was poleaxed by the Basque defender. Messi, by contrast, has been rightfully protected by referees throughout his career.

In England, Maradona will always be remembered for the ‘Hand of God’ incident in the 1986 World Cup quarter-final in Mexico City. He scored two goals in Argentina’s 2-1 victory, the first a sublime dribble from his own half but the second, where he flicked the ball into the net with his fingers after outjumping Peter Shilton, will forever taint his reputation. The resentment lingers and explains some of the anti-Maradona sentiment in the older generation. An otherwise uninspiring Argentina went on to win the tournament but England put them under real pressure in the final 15 minutes in the Azteca when substitutes Chris Waddle and John Barnes exploited the South Americans’ weakness out wide. Barnes in particular was magnificent, setting up a goal for Gary Lineker. The England striker almost levelled the scores in the closing moments but for a miraculous clearance. The most painful thing for England was that Argentina looked tired and it is possible to wonder whether, had they equalised, Bobby Robson’s team might have won the game and even the World Cup.

When this theory was put to Barnes, he snorted with characteristic bluntness to express his derision. “It’s this simple,” he said. “If we had made it 2-2, Maradona would have got the ball, gone down the field and made it 3-2. No one could stop him.”

The World Cup triumph is often the bedrock of the case that Maradona is greater than Messi. Argentina have not won an international tournament since the 1990s and the Barcelona wizard has been unable to lift his nation to glory. The real measure of Maradona’s majesty came in the club game, though, with the move he made after departing the Nou Camp in 1984. His exploits at Napoli are the stuff of legend.

Against a backdrop of drugs, Camorra crime families and rampant excess, the World Cup-winning captain led the club to their only two titles and the Uefa Cup. Serie A at the time was by far the best league in football. By the time of Napoli’s second scudetto in 1990, the Milan side of Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard were at their peak and winning their second European Cup in a row. The team was packed with names that even now, 30 years on, evoke awe: Franco Baresi, Paolo Maldini, Alessandro Costacurta, Carlo Ancelotti and Roberto Donadoni. There is a compelling theory that Arrigo Sacchi created the best club side of all time at the San Siro. That is arguable. What is beyond dispute is that Napoli topped the table twice and Milan won the title just once in the second half of the 1980s.

Nor was Serie A just a battle between two clubs. This was a golden period in Italian football, when the country attracted the finest players on the planet. Inter, Sampdoria and Juventus were strong in one of Italy’s most competitive eras – they all won the league during Maradona’s six years at Napoli. The best players were not condensed at a small number of clubs. Maradona’s supporting cast was never anywhere near as illustrious as Messi’s and the division-wide standard considerably higher.

It was, however, a more defensive epoch. Rule changes, better pitches and concentration of talent at a small number of big clubs has changed the balance of the game. Two titles for Napoli – their only scudettos – does not look like a huge achievement when compared with Barcelona’s 10 titles during the Messi era but the mere figures do not tell the entire story.

Maradona grew in stature after departing Catalonia but a move to the Etihad will not define Messi’s legacy. That is secure and, even if there is a bitter parting, he will always be Barca’s greatest player. He is the Nou Camp’s shining star ahead of Johan Cruyff, Ronaldinho and, yes, Maradona.

From a wider, less Catalan perspective, Maradona has the edge in the battle between Argentina’s left-footed No 10s for the title of best ever. It is possible to make a case for both men and debate will continue but anyone who says definitively that Messi is the greatest player of all time has no grasp of history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks