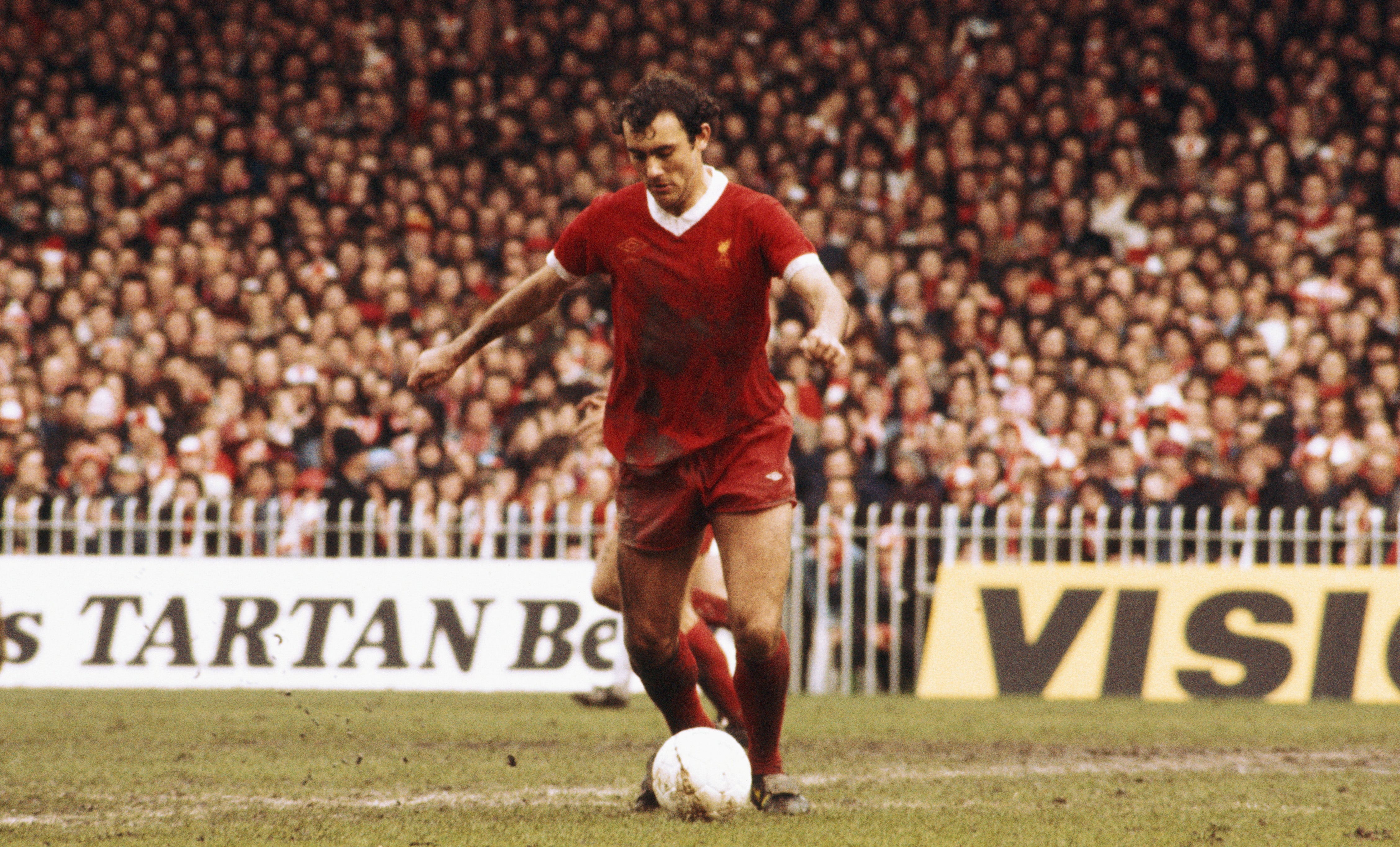

Ray Kennedy was a shining beacon of elegance but packed a heavyweight punch

1951-2021: The former Liverpool and Arsenal player died on Tuesday at the age of 70

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There were some people who thought Ray Kennedy was too big, too awkward and too slow to play in the Liverpool midfield. The 70-year-old, who died today, had an unusual physique for the role. Bill Shankly, who signed him from Arsenal, described Kennedy as looking like Rocky Marciano, the only undefeated world heavyweight boxing champion. Kennedy certainly packed a punch.

Appearances can be deceiving. Kennedy was a shining beacon of elegance in the English game. He glided over the boggy pitches of the late 1970s and early ‘80s. Even in a brilliant Liverpool side packed with superstars, the Northumbrian stood out. He radiated class.

Kennedy had already earned himself a place in football folklore by the time he moved to Anfield in 1974 by scoring one of the most crucial goals in Arsenal history. His strike in the north London derby at White Hart Lane not only gave the Gunners a 1-0 victory over Tottenham Hotspur but delivered the title to Highbury. It was a dagger in the heart for Spurs, who at that point could boast of being the only club to win the Double in the 20th century. Arsenal went to Wembley five days later and beat Liverpool 2-1 in the FA Cup final to emulate their neighbours.

One of the things that characterised Kennedy’s Liverpool career was his ability to pop up unnoticed at the point of danger. His arrival at Anfield might have been a metaphor for this almost supernatural talent. He was signed on the very day Shankly resigned. Merseyside was reeling in shock and hardly noticed that there was a new striker at the club.

Tommy Smith, Liverpool’s bully-in-chief, noticed. There are different versions of the story about how Kennedy was converted to a midfielder, but the commonly told one is that Smith decided to give the new boy a typical ‘Anfield Iron’ welcome to Melwood. The brutal tackle sparked a brawl. Kennedy might not have been Marciano, but he was not a man to back down. Things became so heated that Bob Paisley, Shankly’s successor, thought it prudent to put a little distance between the two men and told Kennedy to sit a little deeper and wider in training. Whatever the catalyst for the switch of position, it was an act of genius.

Liverpool’s left side consisted of two Kennedys. Ray was smooth as silk, with a remarkable passing range and a touch that could kill the ball instantly. Behind him was Alan, another north-easterner, whose relentless running and sometimes scruffy technique earned him the nickname ‘Barney Rubble’. It was a combination of opposites but it worked beautifully.

The bare facts are remarkable. In his eight seasons at Anfield, the midfielder won five titles, three European Cups, a Uefa Cup and a League Cup. He was part of the club’s greatest midfield – along with Jimmy Case, Terry McDermott and Graeme Souness – and never lost his knack of scoring. His goal of the season against Derby County at a ploughed-up Baseball Ground was aesthetically uplifting, a jewel on a dung heap. There were more important strikes, too. The Kop will always remember his third, killer goal in the 3-1 victory over Wolverhampton Wanderers at Molineux, a late shot that put the game out of reach of the home side and inspired a massive pitch invasion to celebrate Paisley’s first title.

His most famous effort was the away goal against Bayern Munich in 1981 that secured a place in the European Cup final. Kennedy controlled an awkwardly bouncing ball on the edge of the box and rammed it home with his second touch, giving an injury-ridden Liverpool the late lead in a 1-1 draw after a goalless first leg at Anfield. Again, Kennedy’s marvellous technique and unhurried calmness were on show.

Kenny Dalglish once described him as a “stroller”. The Scot had sheer admiration in his voice. Kennedy made the game look easy and dictated the pace that he wanted to play at, a rare quality even in those Liverpool teams. And all the time he was suffering from Parkinson’s Disease.

The early signs were there even during his first season on Merseyside. Doctors would later see abnormal movements of his right arm in the highlight clips of his great performances. Kennedy carried on and ignored the traits as they sneaked up on him until he was diagnosed in his mid-30s.

He fell on hard times after he retired and had to sell his memorabilia. His hard-earned medal collection resided in the glass-topped desk of Gordon Taylor, almost lost among the treasures that the chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association gathered for his own viewing pleasure.

Meanwhile, a group of supporters came to Kennedy’s aid when the writer Karl Coppack organised the Ray of Hope Appeal in 2008. The money raised made life more comfortable for Kennedy and brought together Liverpool and Arsenal fans, who were united in fundraising.

His style of football reflected Kennedy’s personality, which was seemingly low key but underpinned by a sharp wit. He hated being confused with his teammate Alan, and a misunderstanding about who was who at a hotel in north Wales led to a bout of rage, which was uncharacteristically explosive. The outburst was a symptom of his undiagnosed illness.

Normally, the midfielder was one of the coolest heads in the heat of battle.

There are a number of players from the Liverpool teams of the 1970s and ‘80s who can make a case for being the most under-rated figure of the era. Kennedy’s is the most compelling. No one who played with him, against him or watched him from the terraces on a regular basis will ever overlook his greatness.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments