Where coal was king and football was a religion

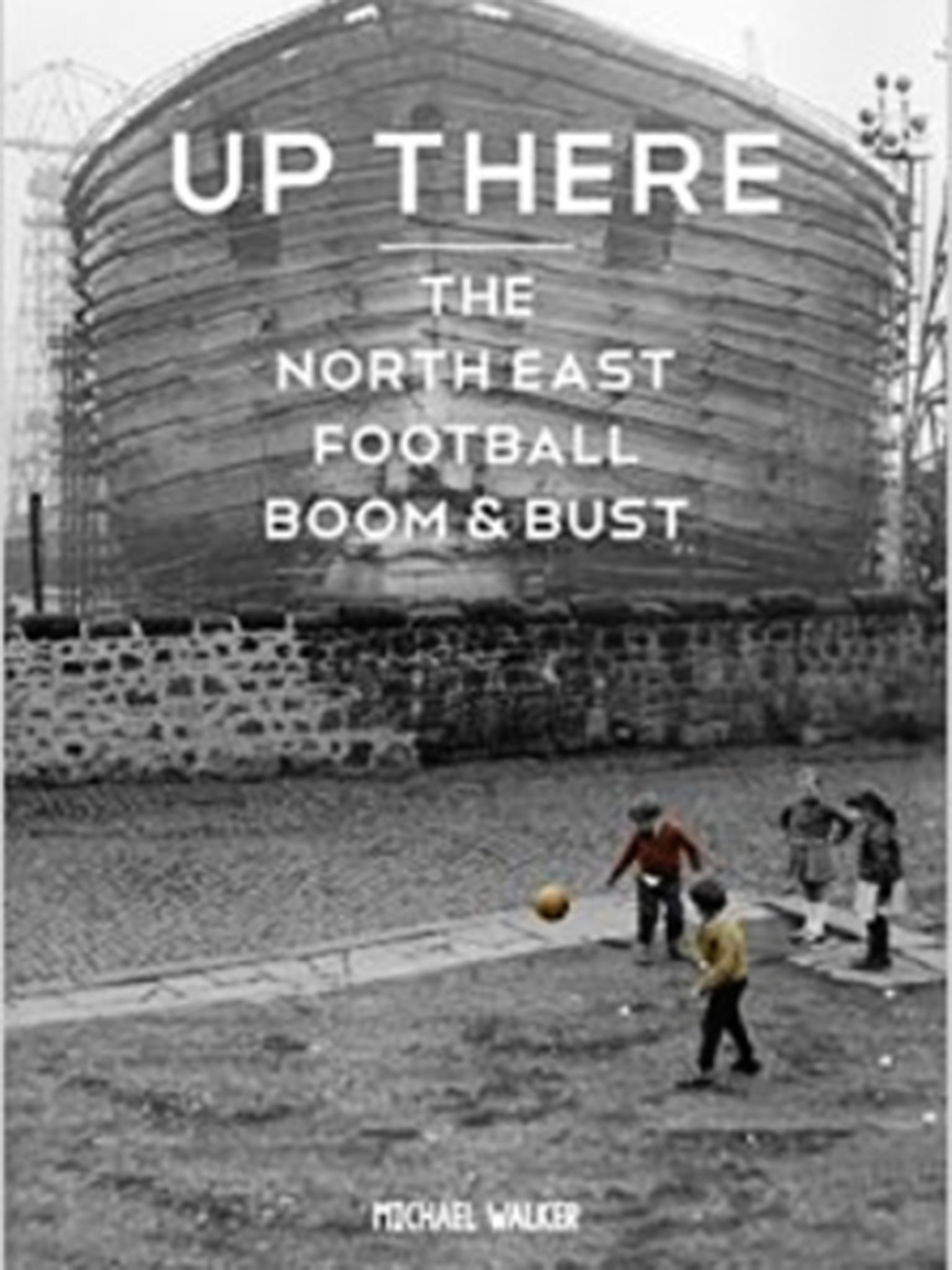

Michael Walker, author of ‘Up There’, a brilliant book about football in the North-East, considers the area’s unique relationship with the game and asks why it’s still strong despite the lack of trophies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jackie Milburn could not wait. Christmas morning, 1932, and the eight-year-old Milburn saw a new pair of football boots at the bottom of his bed. It was 4am. That, though, could not stop the boy who would become Wor Jackie slipping from his Ashington home and making for nearby Sixth Row, where his granny lived.

“I ran as fast as my legs would carry me,” Milburn would recall. “As several other young fellows I knew were going to have boots as presents, I meant to be first on the scene when the big get-together came about.

“But I was disappointed. When I arrived at Sixth Row – and remember it was only just after four o’clock on Christmas morning – most of my friends, wearing their new boots, were playing football by torchlight in the middle of the street. It nearly broke my heart. There were so many lads playing I had to wait nearly 10 minutes before I could eventually get a game.”

You could start the story of North-east football 40 years earlier, when Sunderland were crowned champions of England for the first time, or 64 years later, when Newcastle United broke the world transfer record to bring Alan Shearer back to Tyneside for £15m; but there is something about Milburn, from his early days in the Ashington Midget League and this recollection, that captures the deep bite the game has on the region.

A Tyne-Wear derby weekend is a moment for reflection, particularly one that could be as poignant or prickly as this.

When Newcastle and Sunderland players emerge at St James’ Park tomorrow, it will be from the Milburn Stand, named for a man whose ashes were scattered on the turf.

Jackie Milburn’s life and times combined two of the great unifying threads of 20th-century North-east identity: coal and football. Without the first there would be no second because it was coal and its associated industries such as shipbuilding and railways that gave the area its people. In 1801 the population of Newcastle was 34,000; in 1901 it was 234,000.

Coal provided the North-east with definition, employment and prosperity. As Bill Lancaster of Northumbria University told me: “Newcastle in the 19th century controlled the world’s most important commodity, which was coal. This is 19th-century Dallas.”

If the vast majority of the new population could be considered working class, there was nonetheless a collective economic strength and by the start of the 20th century many of that population had fallen under a spell that continues to bind today. As Bob Paisley put it when describing Hetton-le- Hole, the Durham mining village where he was born and raised: “Coal was king and football was a religion.”

Football in the North-east, Paisley said, should be understood “not just as a recreation, but as a way of life”.

One of the greatest figures in the history of English and European football, Paisley’s achievements and fame sprang from Liverpool. But he was a County Durham boy and, like Milburn, the son of a miner.

Paisley combined coal and football. He also personified a third rich, if not enriching, ingredient of North-east life: departure.

When contemplating something as broad as what the North-east has given to football, and what football has given to the North-east, one of the unavoidable elements is sheer enthusiasm for the game. One of the most striking aspects of that fanaticism is that for the past 60 years it has had little basis on success, and unquestionably one of the reasons for that failing is talent that left either because it was overlooked locally or because it was spirited away by more zealous clubs.

Even before Newcastle were knocked out of the Capital One Cup at Tottenham on Wednesday night, 2015 was going to mark the 60th anniversary of the club’s last major domestic trophy.

Milburn, of course, was in the Newcastle team that won the 1955 FA Cup and few thought then that the club would drift to such an extent that the 1969 Fairs Cup would be their last significant trophy.

Sunderland won the FA Cup in 1973 but it was as a Second Division club; Middlesbrough won the League Cup in 2004, but that was the first major trophy in their then 128-year history.

Boro, Sunderland and Newcastle have all been relegated since that afternoon in Cardiff when Boudewijn Zenden scored the winner against Bolton for a team composed of players from Australia, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Brazil and Cameroon, as well as England. It’s a far cry from Wilf Mannion.

Those subsequent relegations are a reminder that when the shiny new Premier League was formed in 1992, neither Sunderland nor Newcastle were in it. Boro were; they were relegated in the first season.

Below the three “big” clubs, it has been a similar tale of fervour in the face of frequent failure.

In 1927, the last time Newcastle United were champions of England, Sunderland came third. Middlesbrough won the Second Division that season, which contained South Shields and Darlington. In the Third Division North Hartlepools United were joined by Durham City and Ashington. The North east had seven professional Football League clubs.

Next May, should Hartlepool be relegated – and they are currently in 92nd spot – there would be just three in the top four divisions.

The theory that geography is a decisive factor is worth debate. The book title Up There comes from an anecdote told by Howard Kendall when he was Everton manager and Mickey Thomas refused to play for the reserves “up there” at St James’ Park.

The perception of distance has decreased with easier and increased travel. Still, the fans travelling furthest over the course of a Premier League season are those from Newcastle and Sunderland.

John Barnwell provided as convincing an explanation as geography for decades-long under-achievement when he mentioned complacency.

Barnwell, like Paisley and Kendall, is one of the departed. At 16, in 1955, Barnwell, from Newcastle, was one of the most sought-after boys in England. But he did not join Newcastle United: Barnwell signed for Arsenal.

“The area had so many talented players,” Barnwell said, “the local clubs abused that. The best place in England to go for young players was the North-east.”

As early as the 1920s The North Mail had a column titled “The Football Nursery” and when fans of Blackpool and Charlton next pass by the statues of Stan Mortensen and Sam Bartram, they are looking at men from South Shields.

Bartram was in goal when Charlton won their one and only major trophy, the 1947 FA Cup. He was one of five Geordies in the team, as well as manager Jimmy Seed, from Consett. Opponents Burnley had three. Of 20 Englishmen on the pitch, eight were from the North-east, playing for two clubs nowhere near the Tees or Tyne.

That level of influence carried on in the dugout and into the England team. Harry Potts, who went to the same Hetton-le-Hole school as Paisley, was one of those three Burnley players. In 1960 Potts managed Burnley to the League title, and in 1961 to within half an hour of the European Cup semi- finals.

In 1963, and again in 1970, Harry Catterick, born in Darlington, led Everton to the title. On it went via Don Revie at Leeds and Brian Clough at Derby County and Nottingham Forest. Revie and Clough were born a 10-minute walk apart in Middlesbrough.

Add Paisley and between 1960 and 1987 there were 15 League titles won by six managers from the North-east. Six men from within a 19-mile radius. You could call it a cluster.

The silverware tally rises when cups are included. From within the same radius came Jimmy Hagan (West Bromwich Albion), Bob Stokoe (Sunderland), Lawrie McMenemy (Southampton), Bobby Robson (Ipswich Town) and Barnwell (Wolves). Between 1960 and 1990, 31 domestic trophies were won by North-east managers. Add European trophies and the total is 41. It is a torrent of achievement with one obvious flaw – only Stokoe won a trophy with a North-east club.

Similarly, the production line of players was of such volume and ability a post-war North-east XI could be: Bartram; Colin Todd, Jack Charlton, Norman Hunter, Alan Kennedy; Paul Gascoigne, Bobby Charlton, Colin Bell, Ray Kennedy; Mortensen, Shearer. Hunter and Todd were the first two winners of the PFA Players’ Player of the Year award.

That 11 omits players of the calibre of Bryan Robson, Peter Beardsley and Chris Waddle. Along with Gascoigne, this North-east quartet started the opening England game of Italia 90. The manager was Bobby Robson.

By contrast, the England influence, which reached its peak with the Charltons in 1966, was, 24 years after Italia 90, down to Jordan Henderson and Fraser Forster, who went to Brazil as third-choice goalkeeper.

The FA Cup and title-winning influence was down to Michael Carrick, the only North-east starter in the first 10 Cup finals of the 21st century. The managerial influence is down too. Since 1990 only Brian Little has won a domestic trophy, the Aston Villa manager coming from Newcastle. Steve Bruce is now the only North-east manager in the Premier League.

Globalisation hit the area. Jean-Marc Bosman was a spiritual descendant of George Eastham, who won the first freedom-of-contract battle – at Newcastle United. On last season’s opening day Newcastle named a starting XI born abroad (including the Tyneside-raised but Nigerian-born Shola Ameobi) though the club is consciously recruiting locally again.

Industrially, mining and shipbuilding had already gone by the time of Bosman’s 1995 judgement and as former Ashington MP Denis Murphy said: “It was about more than just a pit. It was about a town and what it supported. Ashington once had five cinemas, now it’s got none.”

It still has a team. Ashington play in the Northern League, 125 years old last year. Fans are returning to it.

And they still go to Newcastle and Sunderland. They had the third and seventh highest attendances in the Premier League last season, for teams which finished 10th and 14th.

They might not win trophies any more, and there are challenging local issues that have seen Middlesbrough FC set up a food bank and Newcastle United Supporters Trust help establish a new credit union to combat Wonga. But the game endures. It still matters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments