Sir Matt Busby documentary: Manchester United and a story of faith and perseverance against all odds

The film does a superb job of painting the broad brushstrokes while leaving some deep emotional impressions, but there are areas where you feel more could be delved into – especially that darker side

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

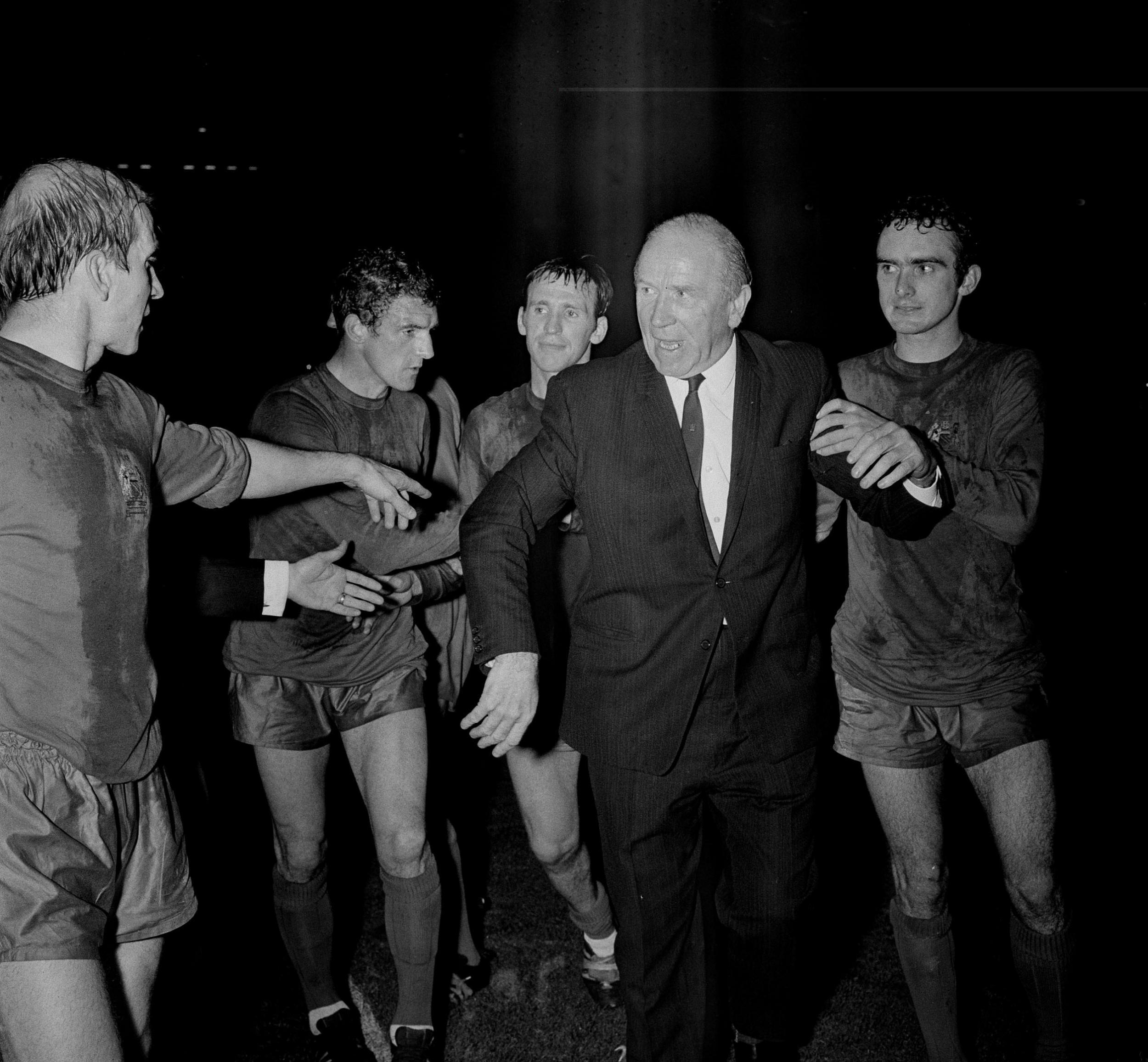

Your support makes all the difference.As Sir Matt Busby walked into the dressing room, there was a silence, a trepidation over what he would say next.

It was half-time in the cavernous Santiago Bernabeu Stadium, and Manchester United were staring into the abyss – both in a sporting sense and emotionally. They were 3-1 down to the great Real Madrid in the second leg of the 1967-68 European Cup semi-finals and, although it was still only 3-2 on aggregate, they never looked further away from finally winning the competition.

It is difficult to overstate just how much this situation, and the next 45 minutes, meant to those involved. It was certainly about so much more than that season’s European Cup. It was about what that grand trophy represented to one man: a life’s work, as well as the tragic deaths of eight young footballers – and, almost, a club.

There are a few other dressing-room scenes in the emotionally stirring new documentary Busby that explain this.

One was when Busby stepped back into the Old Trafford dressing room for the first time after the Munich air disaster. He was visibly limping from his own injuries, that had seen him receive the last rites three times, but it was eyes that really told the story. The spirit had seemingly gone from them. There were tears.

“He was looking at faces that weren’t there,” former player Ronnie Cope says in the film.

Another is from four years after Munich, when Busby had recovered but the team hadn’t. Still trying to get the club back on their feet, the great Scot had been forced to sign players he wouldn’t usually consider of United character. Their approach caused resentment, not least among survivors like Sir Bobby Charlton. A remarkable picture is described by former United player and Busby biographer Eamon Dunphy, as they travelled back from an away game. A sketch was passed back around the bus. It was a crude picture of Busby, his face drawn to resemble a penis and testicles, with the caption “bollock chops”.

The utter lack of respect for one of the most revered figures in football, who had at that stage survived devastating tragedy just four years before, is actually jarring.

“The United dream was dying,” Dunphy says. And yet, a mere four years after that, they were back in the European Cup semi-final against Partizan Belgrade. They were defeated 2-1, leaving Busby as deflated as he’d ever been in the dressing room afterwards. When it finally emptied out, and it was just the manager and close confidante Paddy Crerand left, he finally let it out.

“We’ll never win the European Cup now,” Busby said. Crerand tried to reassure him, but admits now he didn’t really believe it himself.

There was still one last chance, though, that itself looked to be dying in Madrid. United had been bad, as if unable to seize the opportunity in a flat manner that was as dispiriting as the scoreline. Busby should have been furious. Crerand was expecting a volley.

“Can you imagine, we’re sitting in the dressing room in Madrid in 1968, losing 3-1, and Matt comes in to have a go at us,” Crerand tells The Independent now. “And he never swore once.

“In all the years I’ve known Matt, I never heard him swear… and this is a situation where maybe a swear word wouldn’t have done much damage.

“And don’t forget, where Matt grew up just outside Glasgow, you’d argue the first language was actually swearing. It was a natural thing, ‘F’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ would flow off the tongue as if a first language. Not Matt.”

Instead, there was a fairly simple message. It was one the players had heard before, but it meant all the more because of the sheer weight of the occasion.

“Go out and enjoy yourselves.”

It was not what was expected, maybe not what was needed, but it was what worked. Really, it worked wonders, in every sense, as United produced a classically attacking United response to save the game with a 3-3 draw – and the chance at deliverance.

This is perhaps the major message from the film, and one that is so relevant to United today, and football as a whole. Busby’s story is really that of the value of perseverance, of persistence, of faith in an ideal against all odds and obstacles.

The film – which stands out for its impressionistic nature given it is entirely told through voice-overs, interviews and images with no narration – certainly does a good job of painting the very different football world that Busby was a part of. It thereby emphasises just how revolutionary Busby was, just how gloriously distinctive he made Manchester United.

Those interviewed talk of the distinctive smell of his pipe. There is the sight of very different, and seemingly more innocent football crowds, there to take it all in rather than take what they feel they are entitled to. There is the quaintness of the RP voice on Pathe news reels calling the city’s red team ‘Manchester’, amid so much footage of players absolutely lashing the ball in from six yards before jubilantly raising both arms to the air.

What best displays this world, though, is the utter awe towards Madrid when they arrived for the Busby Babes’ first European Cup semi-final in 1956-57. They were then a side whose brilliance had only been spoken about rather than seen, so you get a feel for just how exotic they seemed. You realise why those all-white kits seemed so magical, and made such an impression.

It was a cruder sport then, as the footage emphasises. It was also a much more physical sport.

“Violence was such a big part of the English game,” Crerand says. “You could frighten people then. Big strong centre-halves could frighten people. If it was today, there’d be nobody on the pitch at half-time, some of the tackles and what went on.”

And into this, and what really was a world of hard men – how old players looked is something else that stands out – Busby threw a gang of teenagers, playing the most joyful and open modern football.

It was all so unprecedented, so refreshing, so radical.

“That’s why Manchester United became Manchester United,” Crerand says now.

One of Busby’s pitches to parents when signing up so much young talent was that he would “promise to look after their boys” in such a world. It was a line that took on such a poignant tone after Munich.

The scenes from the aftermath of the crash are naturally the most emotionally affecting, but are still handled deftly. Among the most striking is when Busby’s voice is relayed over the PA before match at Old Trafford, recorded from his hospital bed at Munich, the crowd listening in hushed silence.

And there is Busby’s voice, with some remarkable lines.

“Life was very, very difficult for quite some time,” he said, shortly after so sadly listing the names of the Munich dead. “I had a feeling I was responsible.”

And then, most stunningly: “I wanted to die.”

The spirit within wouldn’t die, though. Emboldened by his wife Jean, who directly told him “the boys that died would want you to carry on”, that was exactly what Busby did.

“One was determined to keep Man United on people’s lips.”

“I got this obsession again that United were going to the top.”

You get a full sense of the scale of the Busby story, just how much was in his life: the adventure, the ideal, the radicalism, the spirit, the goals and the glory and the trophies, the true creation of a great club as well as so many great teams, the tragedy, the recovery, the ultimate deliverance, the presence… but also the survivor’s guilt and the darker side of his personality.

“He wasn’t Father Christmas,” 1968 winner John Aston is quoted in the film. “He wasn’t a benevolent figure… he was tight.”

The film does a superb job of painting the broad brushstrokes while leaving some deep emotional impressions, but there are areas where you feel more could be delved into – especially that darker side. You don’t really learn anything new.

Then again, this is the challenge of reintroducing such a story for a new generation, and absolutely everything is touched upon – even if only lightly. There are so many parts of Busby's life – not least that hugely intriguing period in the early 60s, as well as his relationship with Best – that would serve as a documentary in themselves.

What sinks in the most, though, is that sense of perseverance. Many at United now might say this is never more relevant, and necessary.

The film ends with scenes of the 1968 final intercut with the 1999 Champions League final, to implicitly make the link about the values created.

It is something Crerand reminds us of. “It’s often forgotten, when we won the European Cup in 1968 against Benfica, myself and Alec Stepney were the only players really bought in. The rest all came through the ranks.”

This was not a team bought again after the tragedy of Munich. This was a team built again, staying true to its ideals, perhaps personified by George Best.

Faith, and perseverance: the true morals of the Busby story.

Busby is in select cinemas from 11 Nov, own on digital 15 Nov and DVD & Blu-ray 18 Nov

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments