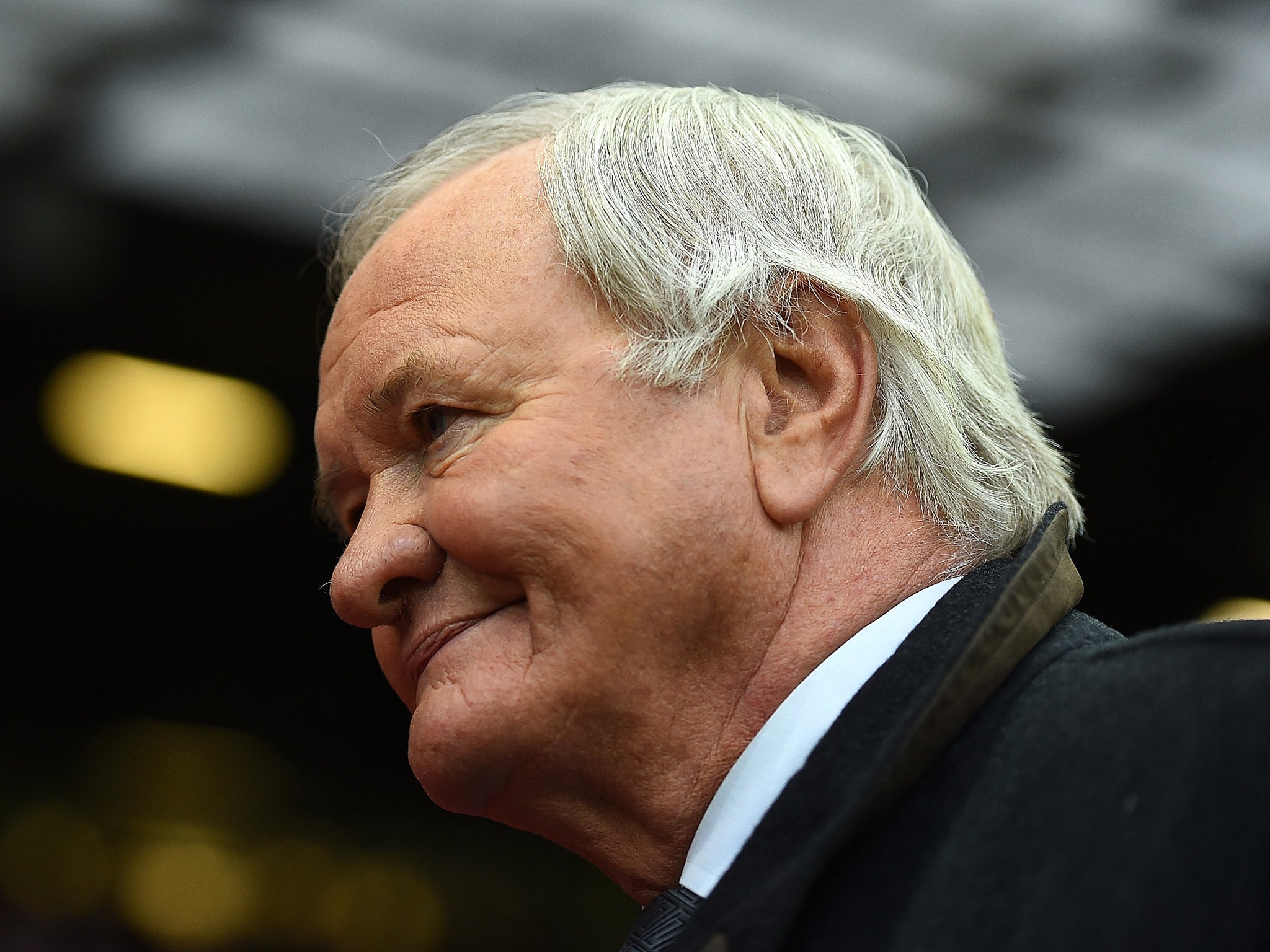

Ron Atkinson: Former Manchester United manager still seeking redemption after all these years from racist storm

When he racially denigrated Marcel Desailly half of the Middle East heard his words. “It’s not the person I am and I’ve certainly learned from it,” Atkinson says now.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.”I want to talk about football. What more can I say about that other stuff now?” asks Ron Atkinson. His pained expression reflects a search for absolution which has already lasted 12 years, demonstrating that it takes just a moment to shred your reputation and the rest of your life to attempt to rebuild it, with no guarantees of succeeding.

Our discussion had reached what the 77-year-old describes as “a phrase I shall always regret” and which barely needs recapping on, given that it – the racist comment finished him as a national football authority – has come to define him. A microphone feed remained on after Chelsea had blown their Champions League semi-final at Monaco in 2004, for which he was an ITV analyst.

When he racially denigrated Marcel Desailly half of the Middle East heard his words. “It’s not the person I am and I’ve certainly learned from it,” Atkinson says now. “All I can do now is let others be the judge.”

No-one can say he hasn’t tried. His discussion of this moment and its aftermath in his new autobiography, co-written with the journalist Tim Rich - is compelling and reveals the distance Atkinson has travelled to put this episode behind him. It is even referenced on the book’s flyleaf. An element of self-justification is evident in Atkinson’s re-telling of it all.

An ITV production assistant who should have disconnected the feed decided she would head to the players’ tunnel that night, a place “where she has no real business to be,” he says. He was repeating a phrase about Desailly that at least two managers he knew had used. Even less convincing: “I didn’t shout it. I mumbled it.”

But more vivid is the story of how he gravitated from being ‘Ron the Manager’ (the title of a Sky Sports series which turned him into a Sir John Harvey-Jones of the football world) to become ‘Ron the Racist.’

He was approached by Adrian Chiles to do a film about the Desailly Affair, entitled ‘What Ron Said’, and wound up on a radio phone-in in America’s Deep South, before arriving at a museum of racist memorabilia. “Halfway through, I asked myself what on earth I was doing here,” he says.

He reached the depths of ‘Wife Swap’, knowing that he would be paired up with a black woman because “they would think it would make good television.” Instead, he ended up with Tessa Sanderson, with whom he got on so well that he and his wife ended up being invited to her wedding.

There is a difference between a racist and the perpetrator of a racist comment and while only those who know Atkinson well are qualified to say if he is the latter, there was a more substantial ethnic dimension to his life in 1980s football than to most of his kind. Not just Laurie Cunningham, Brendan Batson and Cyrille Regis at West Bromwich Albion but Remi Moses, the midfielder he loved when he managed Manchester United.

What football lost when Atkinson put himself beyond its public discourse is evident through the rest of our discussion. It encompasses a managerial career in which he brought attractive football to West Bromwich Albion, Manchester United, Aston Villa and Sheffield Wednesday, collected the FA Cup and League Cup twice and came close to lifting the Premier League trophy in its inaugural year.

He was the one who arrived to make Manchester United great again in the 1981 penury of the pre-Ferguson years when, as he remembers it “Sir Matt Busby owned the club Megastore and only opened it on matchdays” while he, as manager, had to sell players to buy.

“I think I spent £7m and recouped £6m in all,” he says. “The one I really wanted to buy at United was Gary Lineker. I had him all lined up from Leicester for £600,000 but we had to sell first and Everton nipped in.”

He also had the misfortune to find himself up against a Liverpool in their pomp and it was those occasions which generated that sentiment for Moses. “We knew [Graeme] Souness would put some stick about but Remi could dish out the heavy stuff if necessary. He was a terrier and a warrior. And he was a very, very good one touch player.”

His reflections are laced with parallels for the modern, stuttering United. The importance of light and shade in midfield: Ray Wilkins and Arnold Muhren had the silk, manoeuvring the ball into great areas while Moses and Bryan Robson did the heavy lifting.

Knowing that moving players on is not as hard as think: “There’s a natural progression. It’s much harder telling young players they’re not going to make it.”

For Wayne Rooney, read Martin Buchan and Lou Macari for Atkinson. Ferguson would reflect that Atkinson failed to deal with a drinking culture at Old Trafford and wrongly tolerated the presence of Paul McGrath and Norman Whiteside. Atkinson challenges that.

“Alcohol was part of the temper of the times in English football and it was not confined to Manchester United.”

Did Ferguson, who delivered the championships Atkinson didn’t, have something Atkinson lacked?

“You have to remember that United had been in the Second Division only six years earlier,” he replies. “My aim was to get them back into Europe. Time is what Alex was given.”

Such a life, such stories to tell and such regret that ten seconds in a television studio came to transcend it all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments